Logo of the Congressional Budget Office from cbo.gov.

The federal government’s fiscal year runs from October 1 to September 30 of the following calendar year. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the federal government’s budget deficit for fiscal 2024, which just ended, was $1.8 trillion. (The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) will release the official data on the budget later this month.)

The federal budget deficit increased by about $100 billion from fiscal 2023, although the comparison of the deficits in the two years is complicated by the question of how to account for the $333 billion in student debt cancellation that President Biden ordered (which would reduce federal revenues by that amount) but which wasn’t implemented because of a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

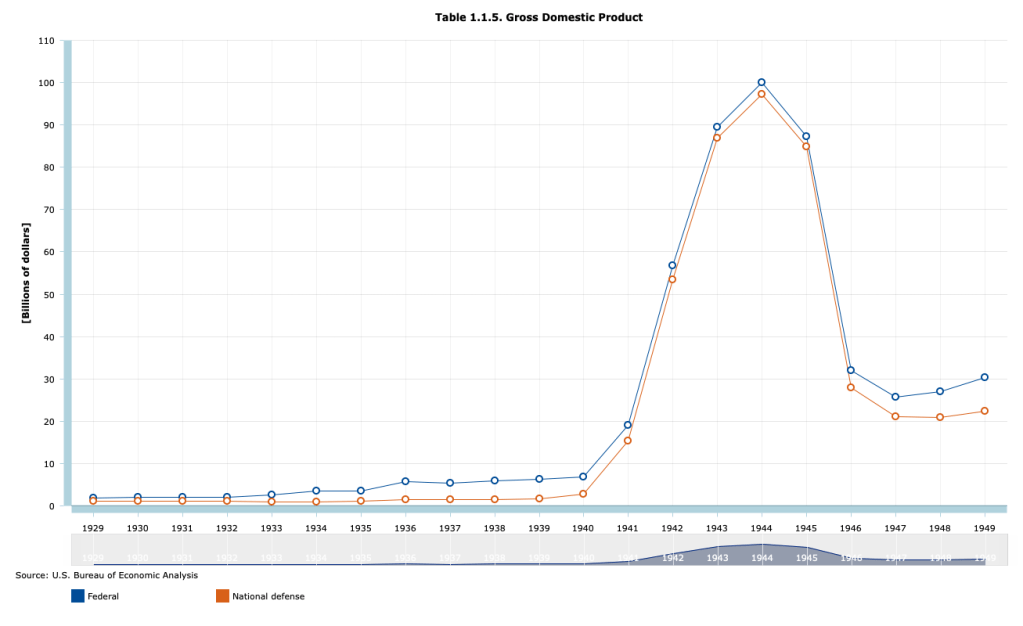

The following table from the CBO report compares federal receipts and outlays for fiscal years 2023 and 2024. Recipts increased by $479 billion from 2023 to 2024, but outlays increased by $617 billion, resulting in an increase of $139 billion in the federal budget deficit.

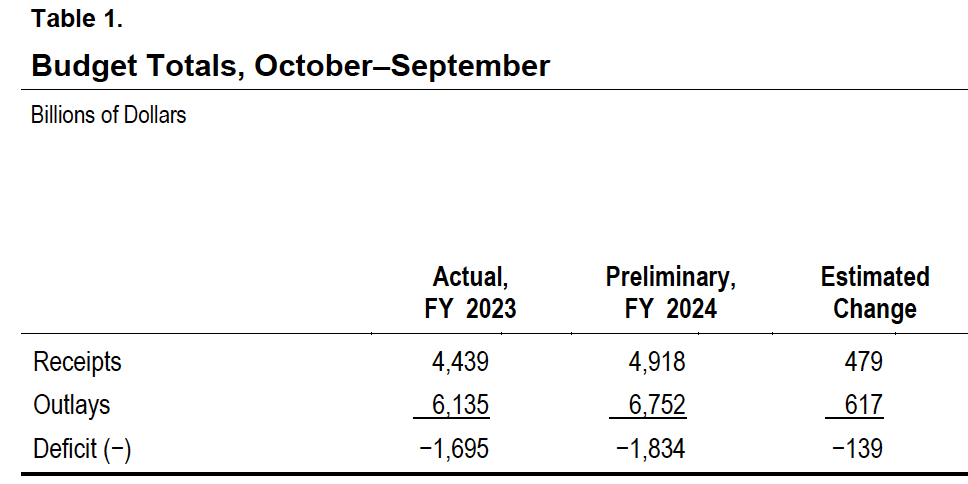

The following table shows the increases in the major spending categories in the federal budget. Spending on the Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid programs increased by a total of $135 billion. The large increase in spending on the Department of Education is distorted by accounting for the reversal of the student debt cancellation following a Suprement Court ruling, as previously mentioned. The FDIC is the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which had larger than normal expenditures in 2023 due the failure of several regional banks. (We discuss this episode in several earlier blog posts, including this one.) Interest on the public debt increased by $240 billion because of increases in the debt as a result of persistently high federal deficits and because of increases in the interest rates the Treasury has paid on new issues of bill, notes, and bonds necessary to fund those deficits. (We discuss the federal budget deficit and federal debt in Macroeconomics, Chapter 16, Section 16.6 (Economics, Chapter 26, Section 26.6).)

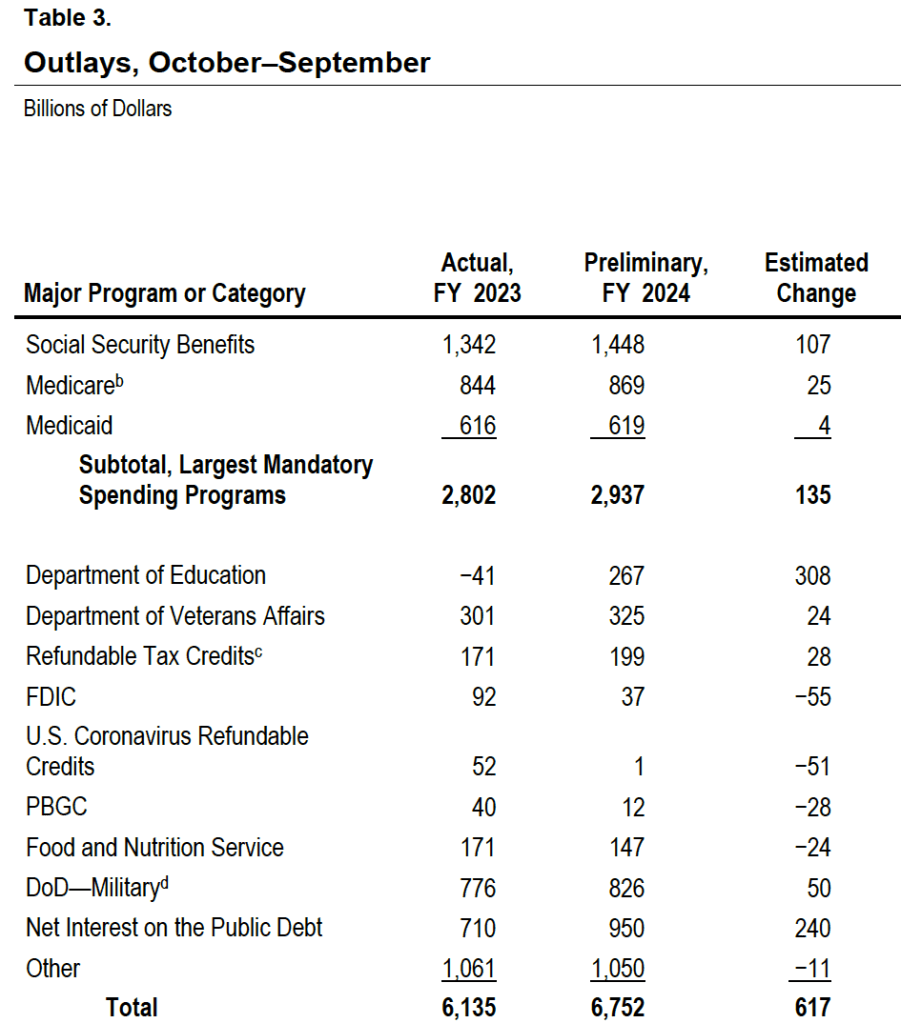

A troubling aspect of the large federal budget deficits is that they are occurring during a time of economic expansion when the economy is at full employment. The following figure, using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), shows that at an annual rate, the federal budget deficit has beening running between $1.9 trillion and $2.1 trillion each quarter since the first quarter of 2023, well after most of the federal spending increases to meet the Covid pandemic ended.

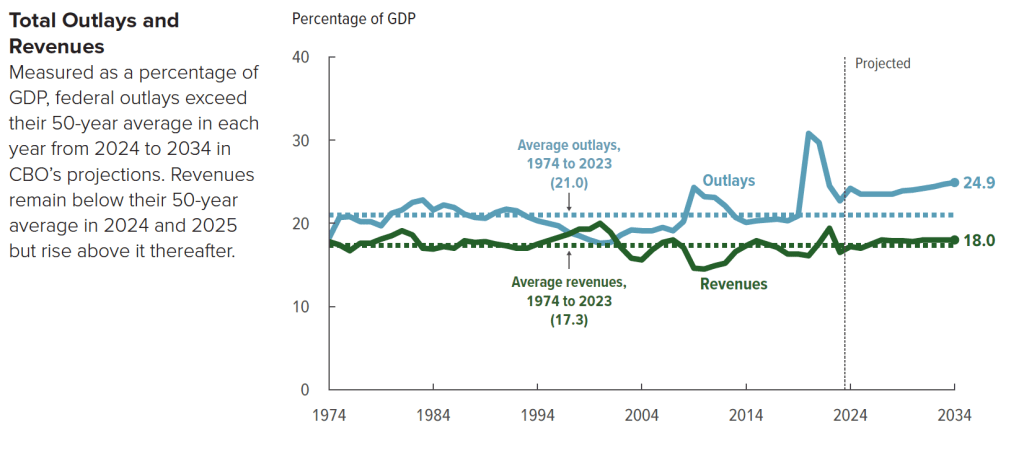

The following figure from the CBO shows trends in federal revenue and spending. From 1974 to 2023, federal spending averaged 21.o percent of GDP, but is forecast to rise to 24.9 percent of GDP by 2023. Federal revenue averaged 17.3 percent of GDP from 1974 to 2023 and is forecast to rise to 18.0 percent of GDP in 2034. As a result, the federal budget deficit, which had averaged 3.7 percent of GDP between 1974 and 2023 (already high in a longer historical context) will nearly double to 6.9 percent of GDP in 2034.

Slowing the growth of federal spending may prove difficult politically because the majority of spending increases are from manadatory spending on Social Security and Medicare, and from interest on the debt. Discretionary outlays are scheduled to decline in future years according to current law, but may well also increase if Congress and future presidents increase defense spending to meet the foreign challenges the country faces.

One possible course of future policy that would result in smaller future federal deficits is outlined in this post and the material at the included links.