Federal Reserve Governor Michelle Bowman (Photo from federalreserve.gov)

Federal Reserve Chairs place a high value on consensus, particularly with respect to the decisions of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) setting the target for the federal funds rate. (Note that the chair of the Fed’s Board of Governors also serves as the chair of the FOMC.) As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 14, Section 14.4 (Economics, Chapter 24, Sectio 24.4), the FOMC has 12 voting members: the 7 members of the Board of Governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and 4 of the other 11 District Bank presidents, who serve rotating one-year terms.

Decisions by the FOMC in setting the target for the federal funds rate are usually unanimous. Prior to the FOMC meeting on September 17-18, each vote of the committee had been unanimous since Esther George, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City cast a dissenting vote at the meeting on June 14-15, 2022. At that meeting, the committee voted to raise its target for the federal funds rate by 0.75 percentage point (75 basis points). George voted against the move because she believed a 0.50 percentage point (50 basis points) increase would have been more appropriate.

At the September 17-18 meeting, Fed Governor Michelle Bowman voted against the decision to reduce the target for the federal funds rate by 50 basis points because she believed a cut of 25 basis point would have been more appropriate. She was the first member of the Board of Governors to cast a dissenting vote at an FOMC meeting since 2005.

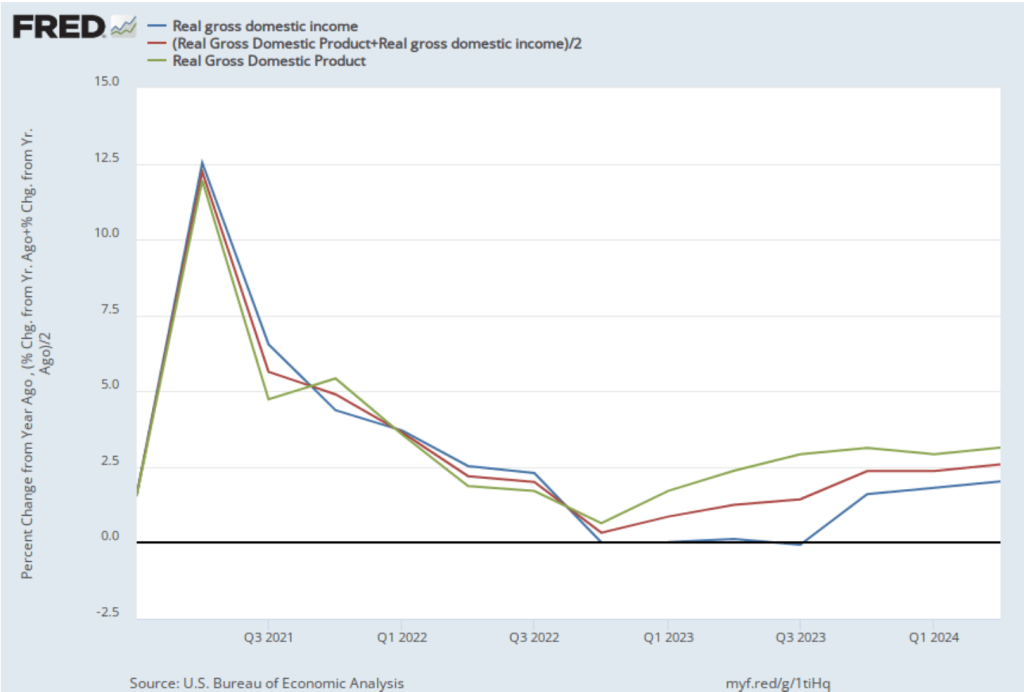

Perhaps because it’s unusual for a member of the Board of Governors to dissent from an FOMC decision, Bowman issued a statement explaining her vote. In her statement, Bowman argued that although inflation has declined substantially over the past two years, she was concerned that inflation as measured by the 12-month percentage change in the core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index was still 2.5 percent—above the Fed’s target inflation rate of 2 percent: “Although it is important to recognize that there has been meaningful progress on lowering inflation, while core inflation remains around or above 2.5 percent, I see the risk that the Committee’s larger policy action could be interpreted as a premature declaration of victory on our price stability mandate.” (Note that the Fed uses the PCE rather than the core PCE to gauge whether it is hitting its inflation target, but core PCE is generally thought to be a better indicator of the underlying inflation rate.)

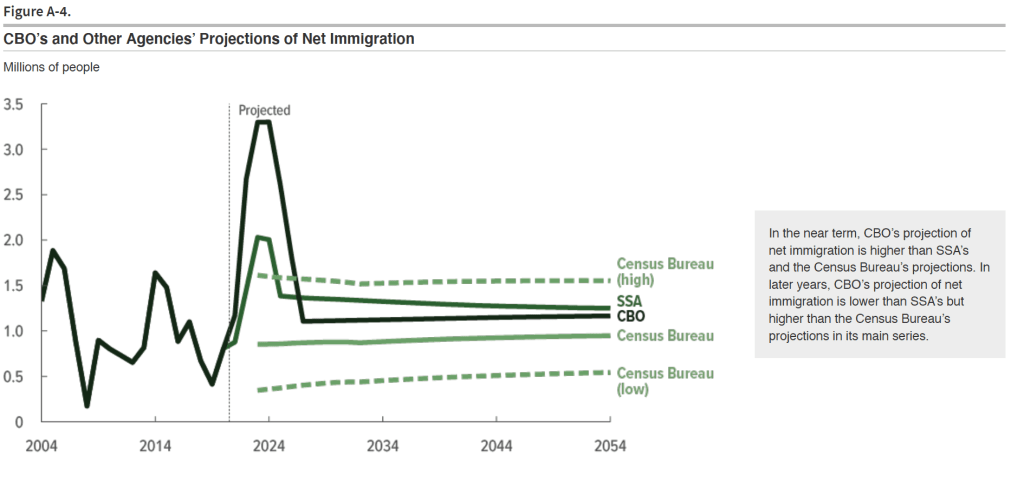

Bowman also noted the difficulty of interpreting developments in the labor market: “My reading of labor market data has become more uncertain due to increased measurement challenges and the inherent difficulty in assessing the effects of recent immigration flows.” (We discuss the effects on employment measures of differing estimates of the level of immigration in this blog post.)