An Automated Teller Machine (ATM) located in Egypt that dispenses gold bars rather than currency. (Photo from ahrm.org.)

A recent article in the New York Times (available here, but a subscription may be required) discusses how consumers in Egypt are dealing with inflation. According to statistics from the International Monetary Fund, consumer prices in Egypt rose 23.5 percent in 2023 and are projected to increase by 32.2 percent in 2024, although in early 2024 inflation may have been running at an annual rate of 50 percent. In response to the inflation, many Egyptian businesses have begun quoting prices in U.S. dollars rather than in Egyptian pounds. The value of the Egyptian pound has declined from about 18 pounds to the U.S. dollar in early 2022 to about 48 pounds to the dollar today. In practice, many Egyptian consumers can have difficulty obtaining dollars except on the black market, where the exchange rate is generally worse than the rate quoted by the Egyptian central bank.

According to the article, many Egyptians, losing faith in value of the pound and unable to easily obtain U.S. dollars, have turned to gold as a potentially “safe financial harbor.” The article notes that: “The market [for gold] grew so fevered that the government announced in November that it was partnering with a financial technology company to install A.T.M.s [Automated Teller Machines] that would dispense gold bars instead of cash.” That ATM is shown in the photo above.

This episode raises two questions:

- Is gold a good hedge (a “safe harbor”) against inflation?

- Are ATMs that dispense gold rather than currency a good idea?

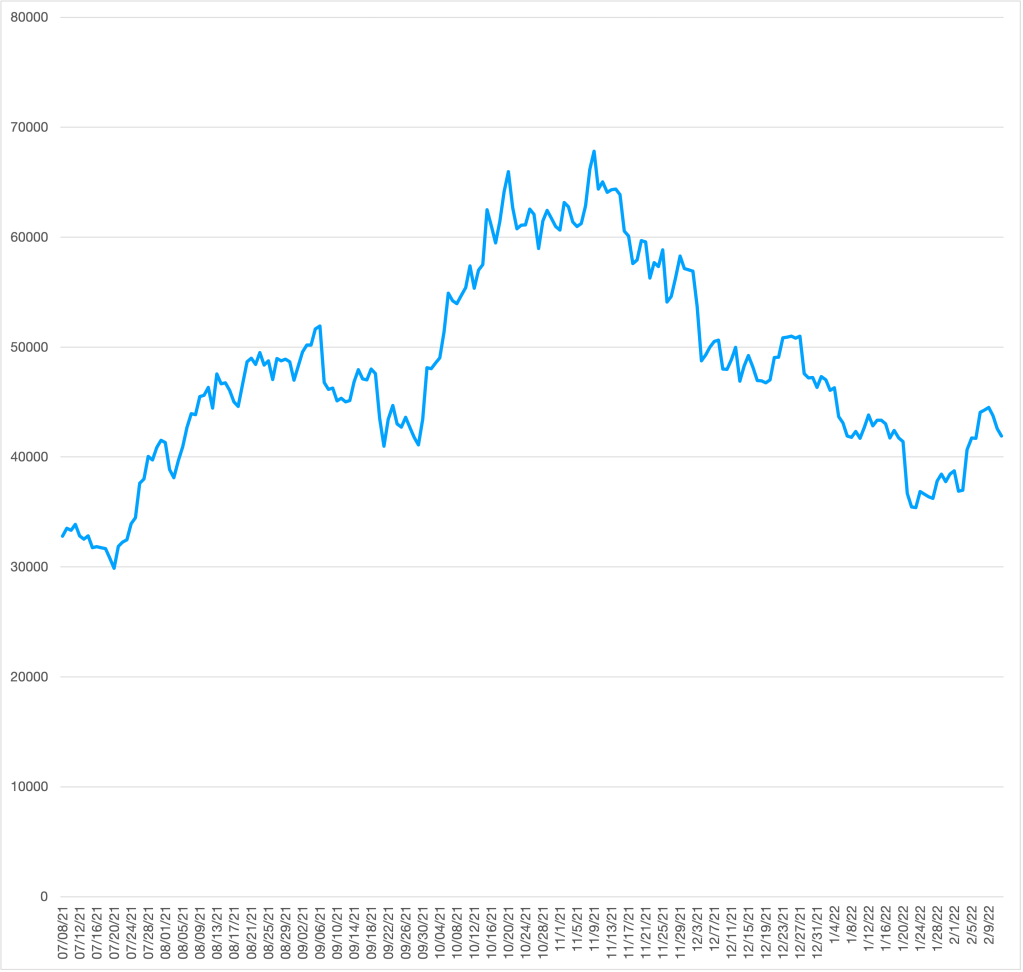

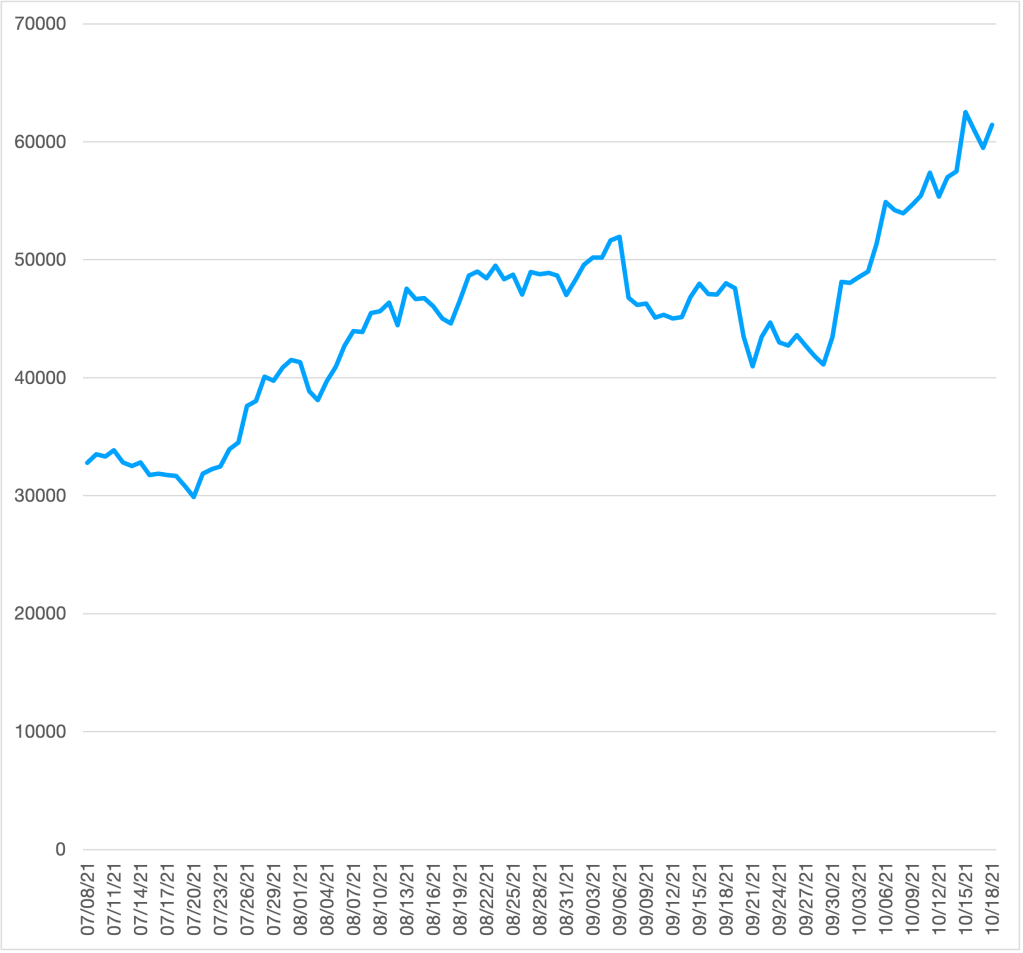

As we discuss in Chapter 14, Section 14.3 of Money, Banking, and the Financial System, gold has not been a good hedge against inflation for U.S. investors. Although many people believe that the price of gold can be relied on to increase if the general price level increases, in fact, the data show that the price of gold can’t be counted on to keep up with increases in the general price level. In the following figure, the blue line shows the market price of gold during each month since January 1976. The red line shows the real price of gold, which is calculated by dividing the nominal price of gold by the consumer price index (CPI). (For convenience, we set the value of the CPI equal to 100 in January 1976.) The price of gold is measured in dollars per ounce.

The figure shows that the market price of gold can fall even as the price level rises. For example, the price of gold rose from $132 per ounce in January 1976 to $670 per ounce in September 1980. As a result, during that period the real price of gold more than tripled, and holding gold during this period was a good hedge against inflation. Unfortunately, the market price of gold then went into a long decline and didn’t again reach its September 1980 value until April 2007, a period during which the CPI more than doubled. In other words, over this more than 25-year period gold provided no hedge at all against the effects of inflation. Consumers in India today shouldn’t count on buying gold as way to protect the real value of their savings from being reduced by inflation.

The New York Times article refers to only a single ATM in Egypt that dispenses gold bars rather than Egyptian pounds. Would we expect that the number of these ATMs will increase in Egypt and other countries experiencing very high inflation rates? Does the existence of these ATMs indicate that people in Egypt are now—or will likely begin—using gold bars rather than currency for routine buying and selling?

The answer to both questions is likely “no.” Although the article refers to an “ATM,” it might be better to think of this facility as instead being a vending machine. Similar ATMs/vending machines that dispense gold bars are available in the United States (as indicated here, here, and here), and, most likely, in other countries as well.

We usually think of vending machines as selling soda and water or snacks. But there are many vending machines that sell other products as well. For instance, most large airports have vending machines that sell small electronic products, such as cell phone batteris or earphones. The term ATM is usually reserved for machines that enable people who have deposits at a bank or other financial firms to withdraw currency. So, the article seems to be describing something that is more a vending machine than an ATM. The article discusses the many small businesses in Egypt that buy and sell gold, which makes it likely that most consumers will continue to rely on those businesses rather than on a machine when they want to buy and sell gold.

It seems unlikely that people in Egypt will beging using gold bars for routine buying and selling—that is, using gold as a medium of exchange. Most goods in Egypt have their prices denominated in either Egyptian pounds or in U.S. dollars or in both. Anyone attempting to buy goods with gold bars would need first to determine the market price of gold at that time before making the purchase and would have to locate a seller who was willing to accept gold in exchange for their goods. In effect, sellers would be engaging in two transactions at the same time: buying gold from the buyer and selling goods to the buyer. Although in a time of high inflation a seller takes on the risk that currency he accepts for a purchase may decline in value while the seller is holding it, a seller accepting gold also takes on the risk that the market price of gold may fall while the seller is holding it.

It’s interesting that the Egyptian government reacted to consumers buying gold as a hedge against inflation by partnering with a financial firm to make available an “ATM” that dispenses gold bars. But it probably doesn’t represent a significant development in the Egyptian financial system.