Image generated by ChatGTP-4o

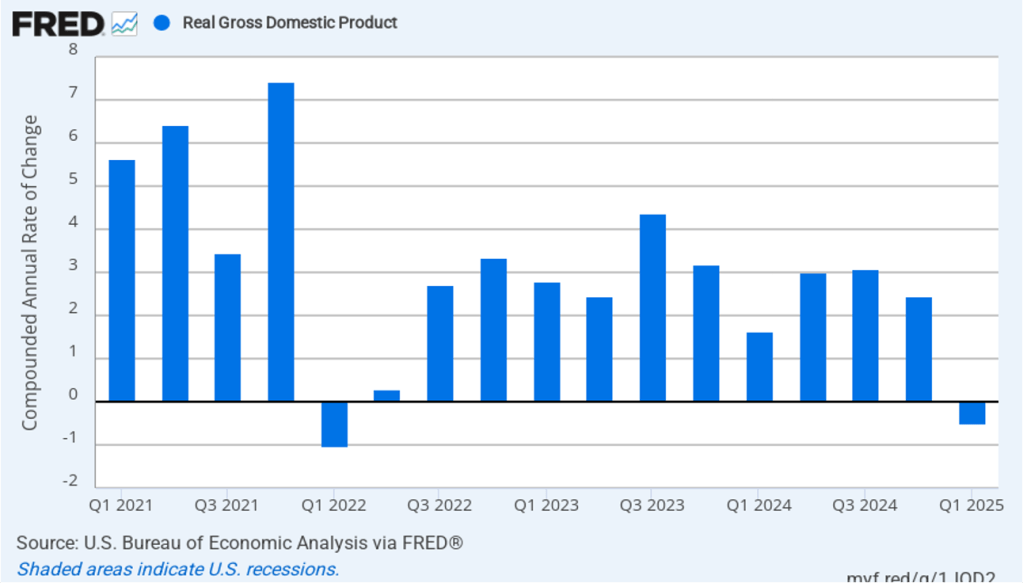

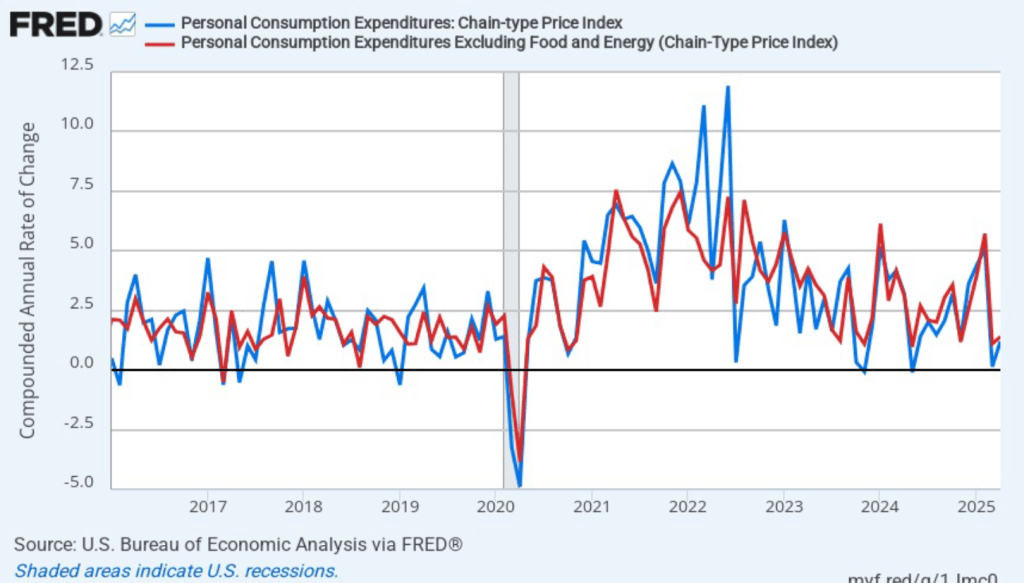

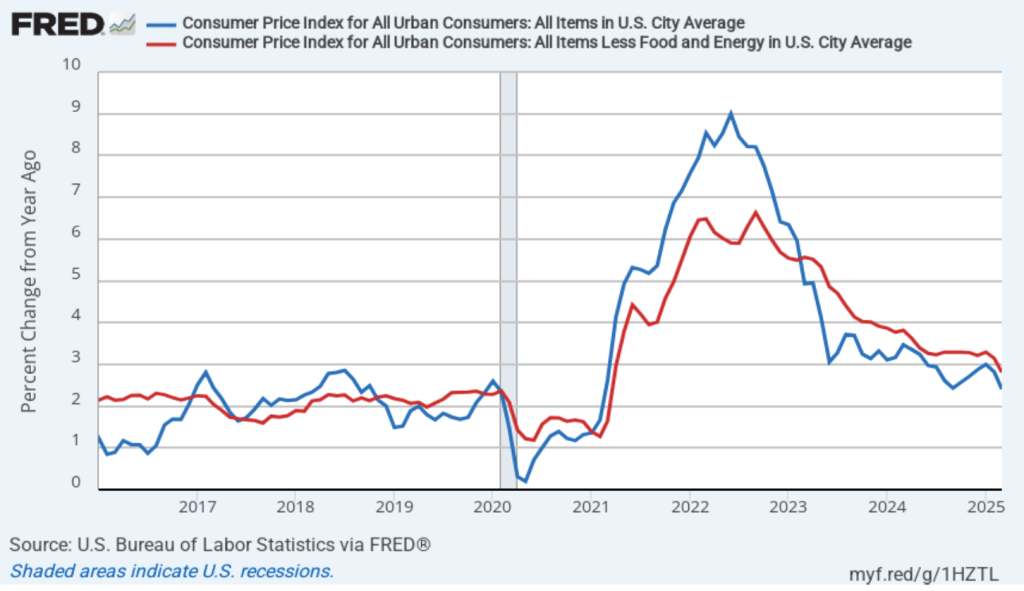

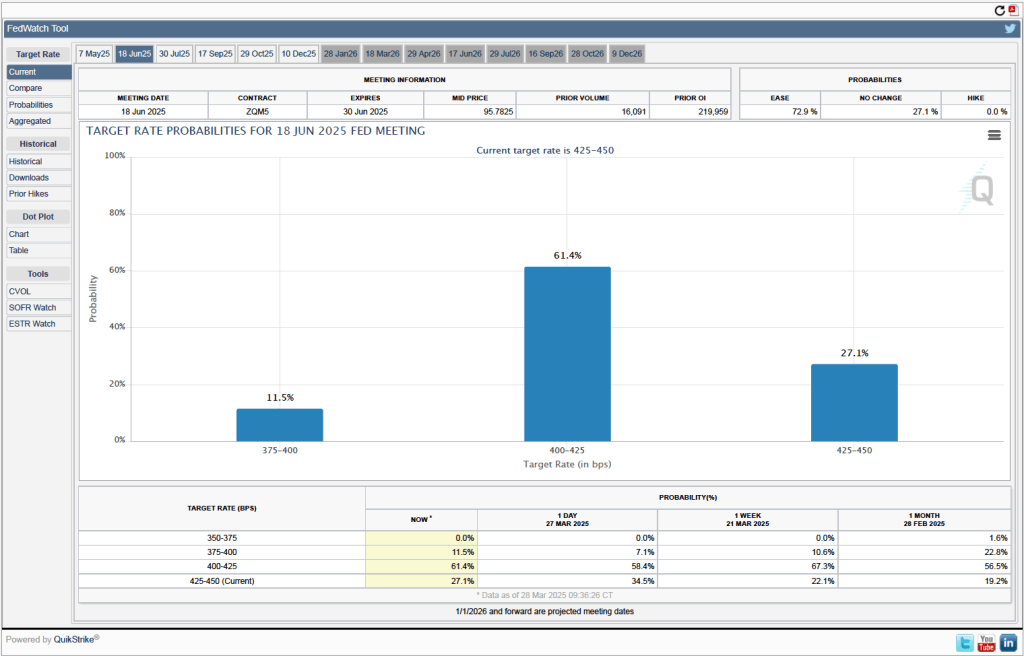

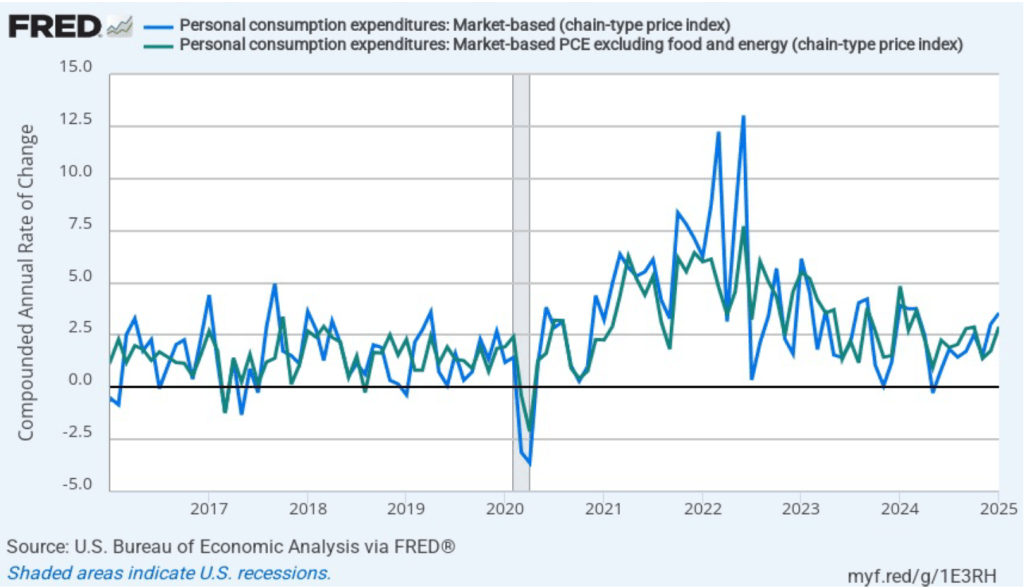

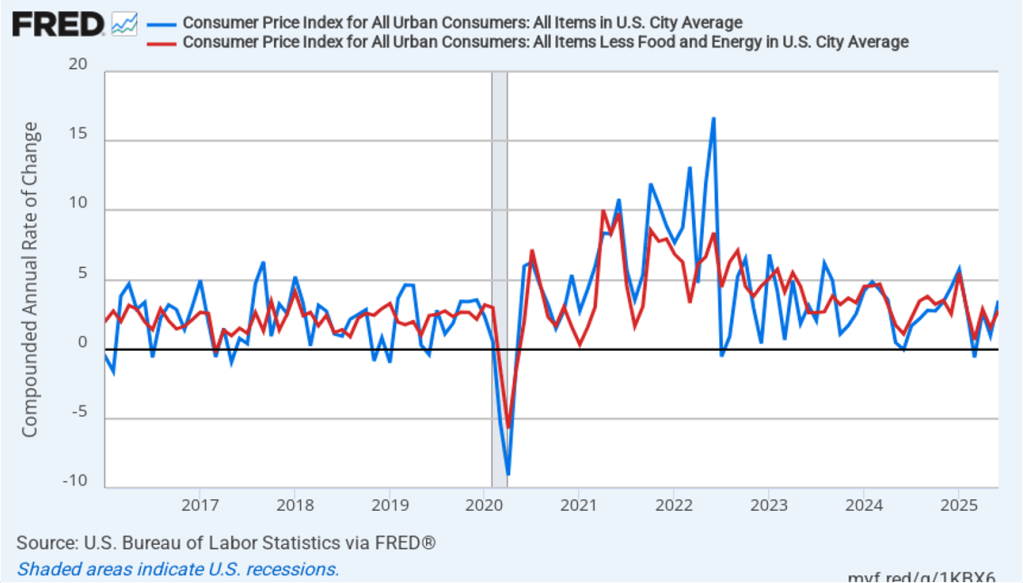

Today (July 15), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its report on the consumer price index (CPI) for June. The following figure compares headline CPI inflation (the blue line) and core CPI inflation (the red line).

- The headline inflation rate, which is measured by the percentage change in the CPI from the same month in the previous year, was 2.7 percent in June—up from 2.4 percent in May.

- The core inflation rate, which excludes the prices of food and energy, was 2.9 percent in June—up slightly from 2.8 percent in May.

Headline inflation was slightly higher and core inflation was slightly lower than what economists surveyed had expected.

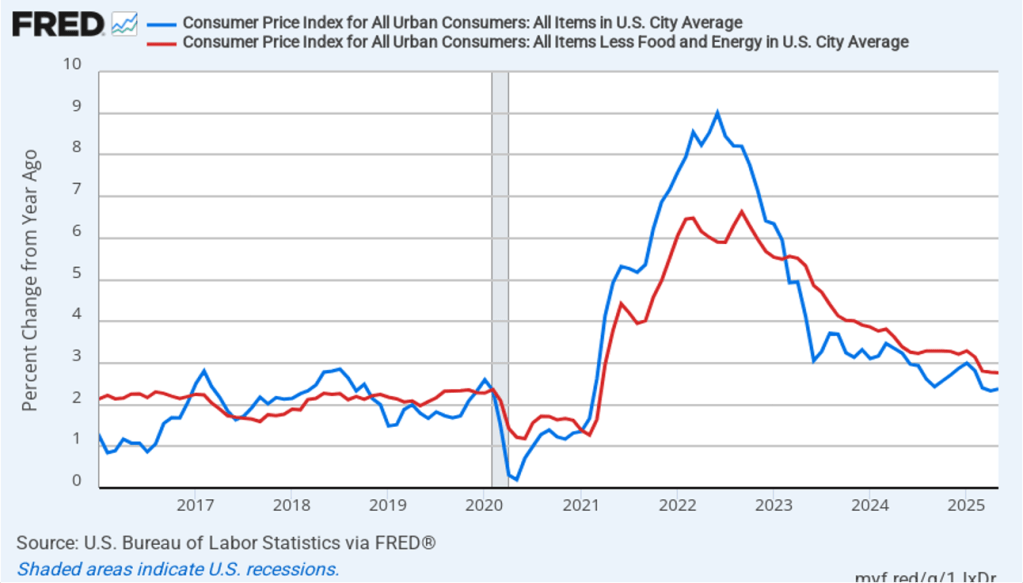

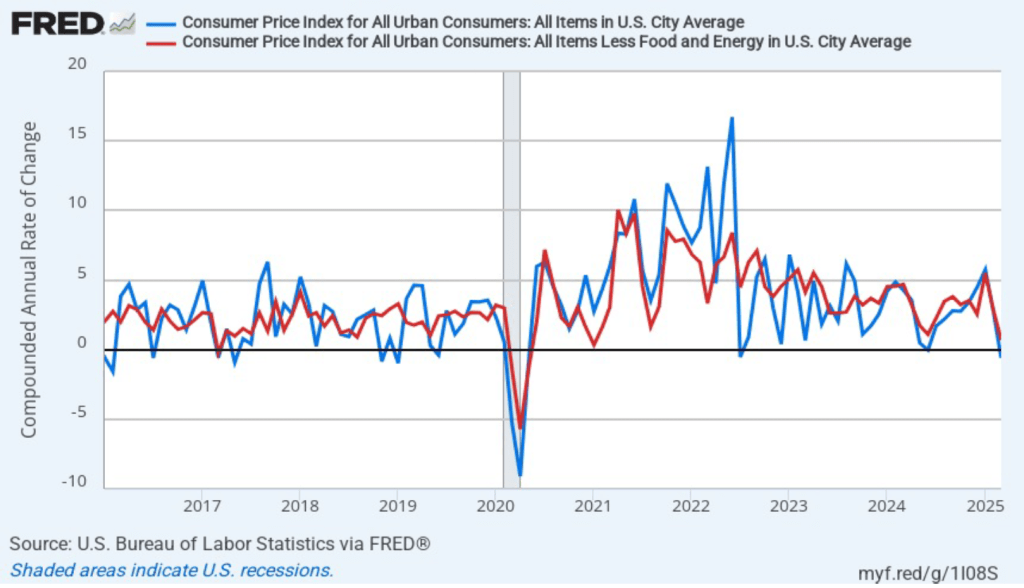

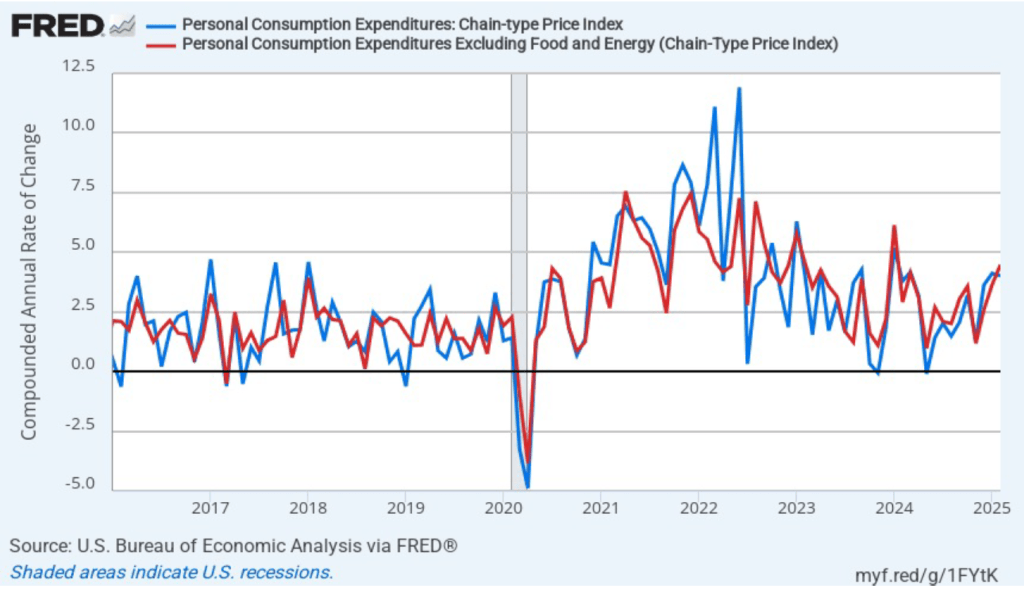

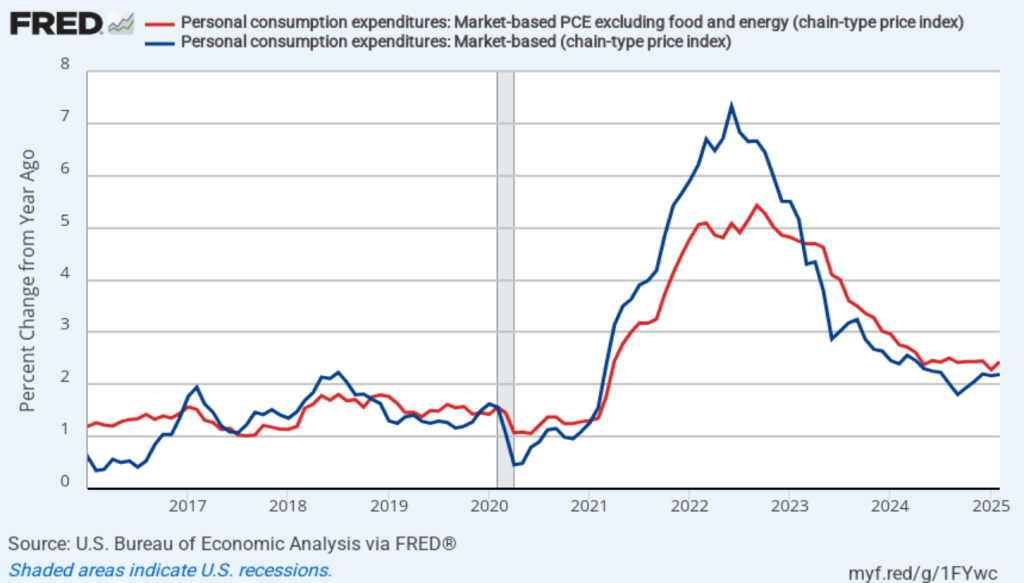

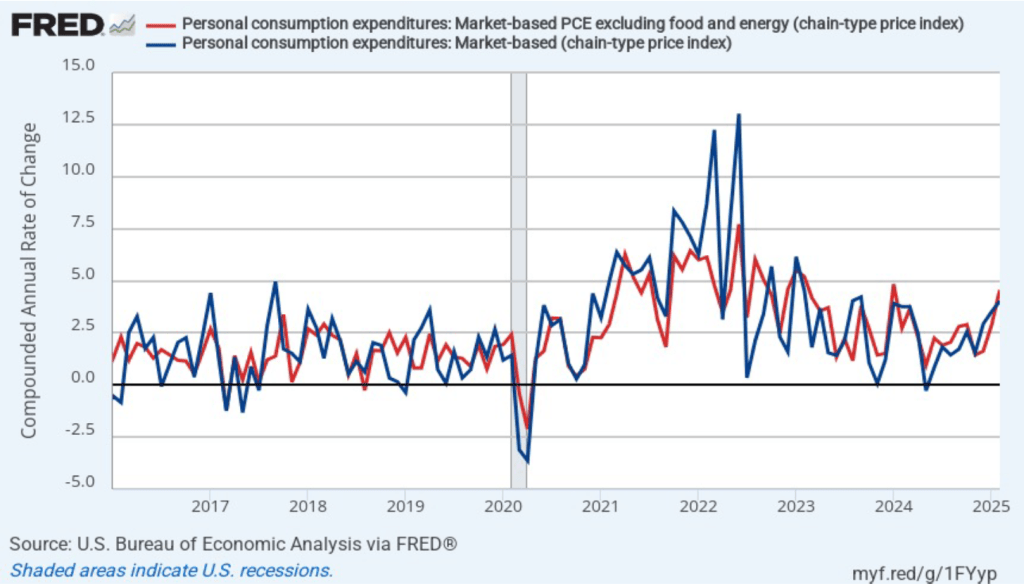

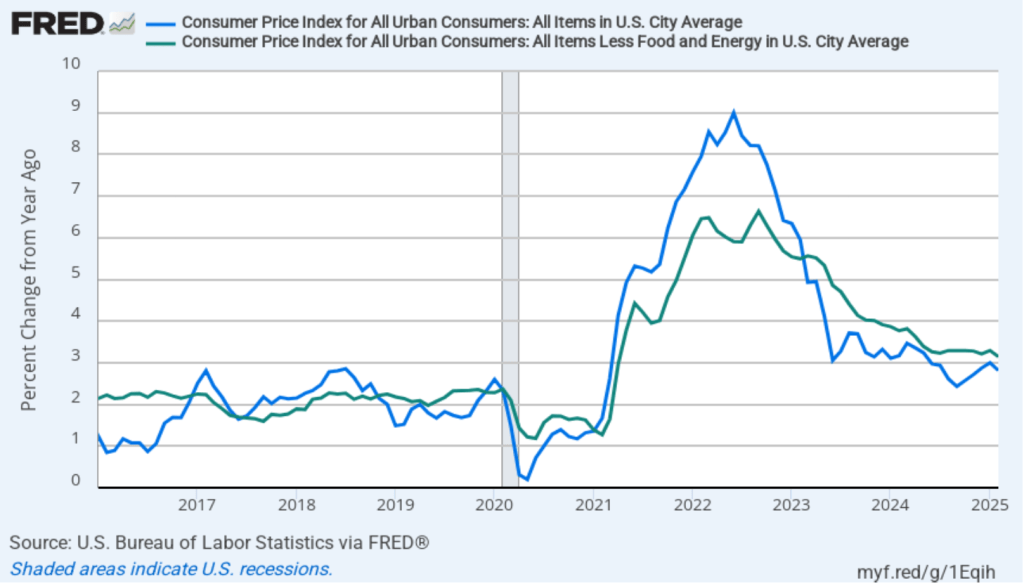

In the following figure, we look at the 1-month inflation rate for headline and core inflation—that is the annual inflation rate calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. Calculated as the 1-month inflation rate, headline inflation (the blue line) surged from 1.0 percent in May to 3.5 percent in June. Core inflation (the red line) also increased sharply from 1.6 percent in May to 2.8 percent in June.

The 1-month and 12-month inflation rates are telling different stories, with 12-month inflation indicating that the rate of price increase is running moderately above the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target. The 1-month inflation rate indicates more clearly that inflation increased significantly during June.

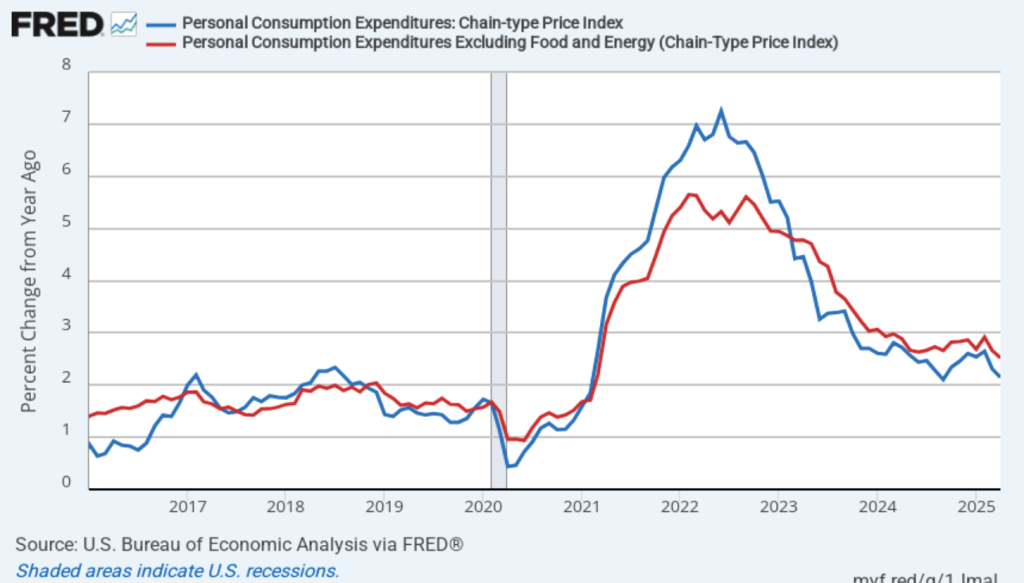

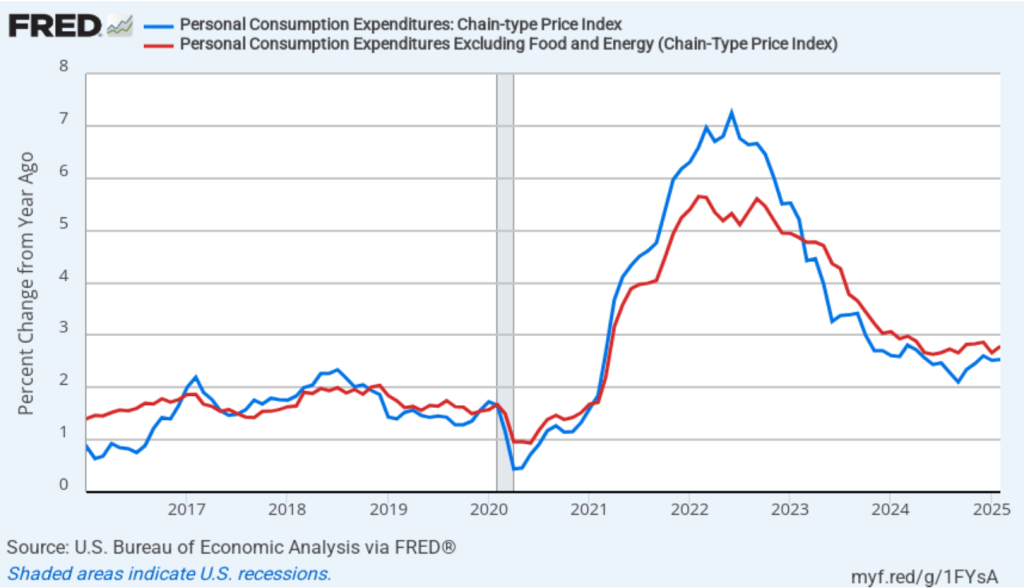

Of course, it’s important not to overinterpret the data from a single month. The figure shows that the 1-month inflation rate is particularly volatile. Also note that the Fed uses the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, rather than the CPI, to evaluate whether it is hitting its 2 percent annual inflation target.

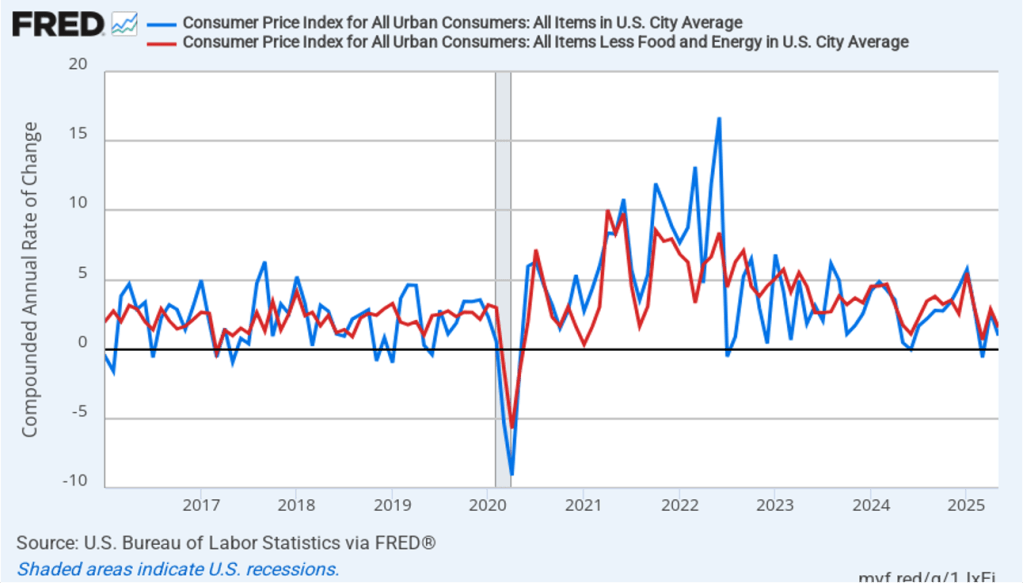

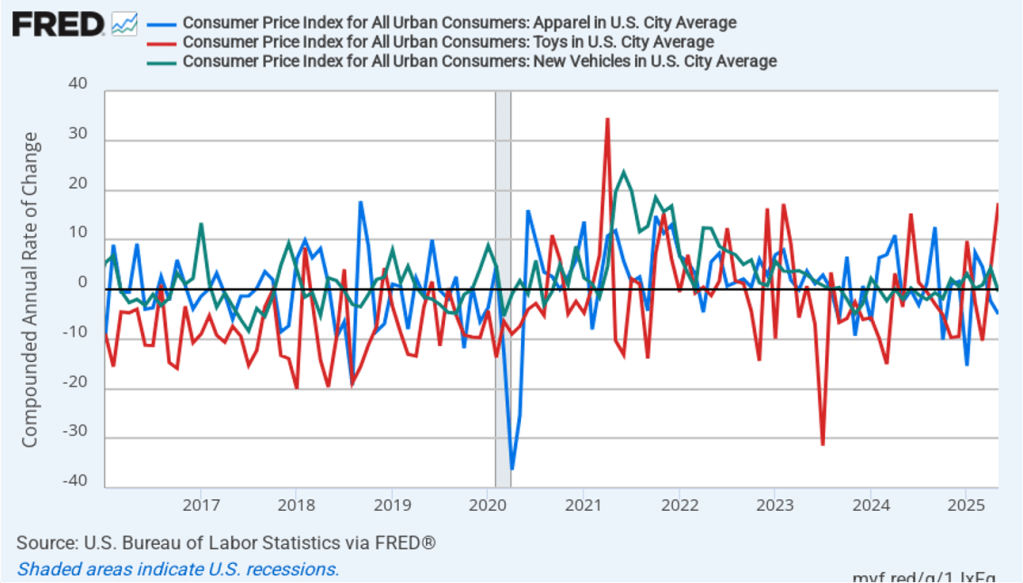

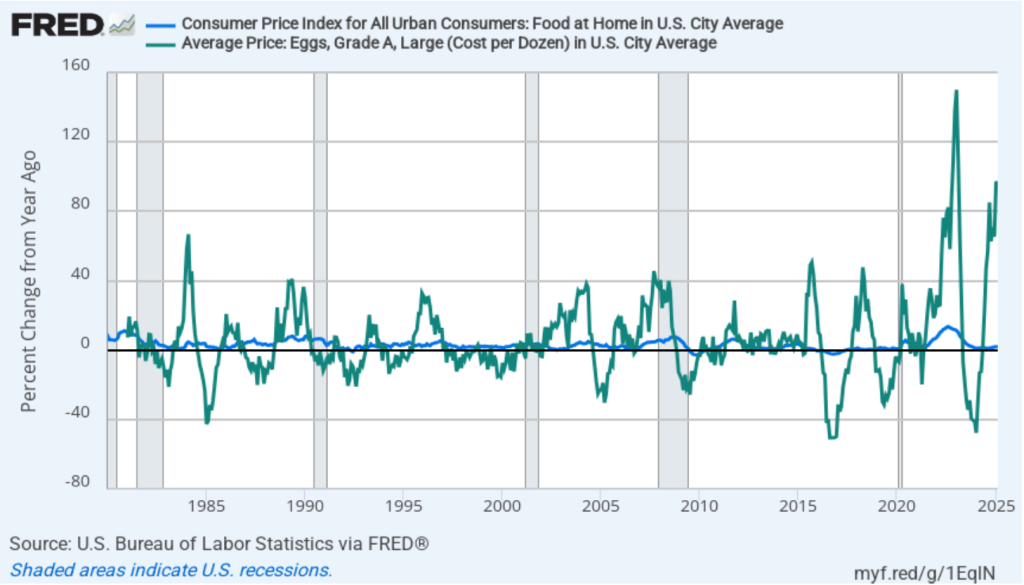

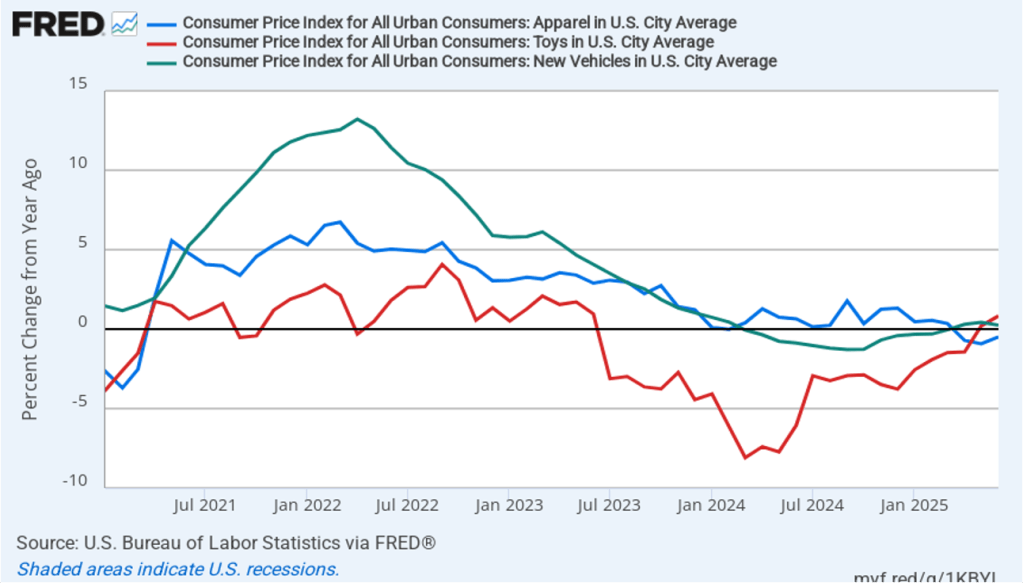

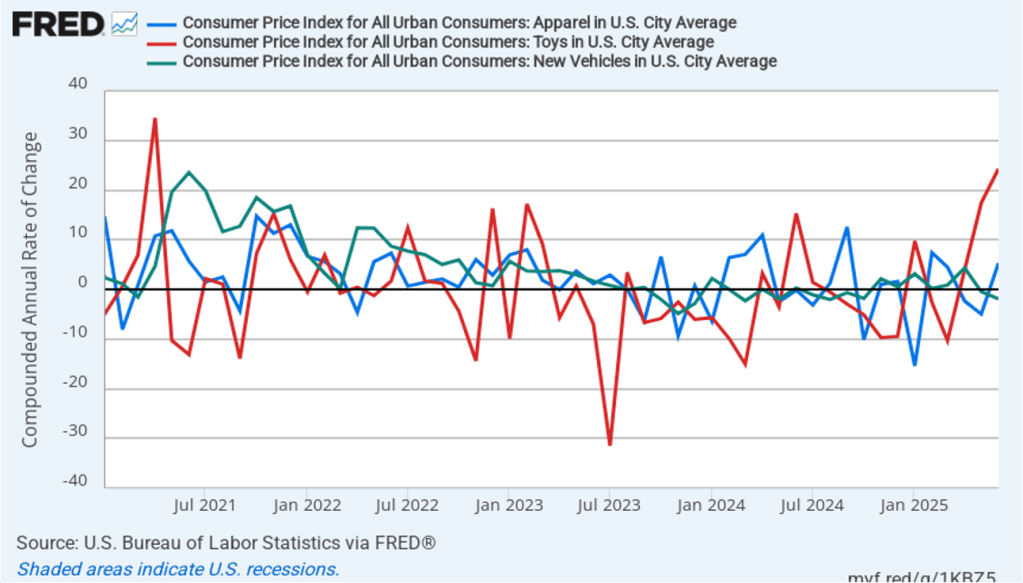

Does the increase in inflation represent the effects of the increases in tariffs that the Trump administration announced on April 2? (Note that some of the tariff increases announced on April 2 have since been reduced) The following figure shows 12-month inflation in three categories of products whose prices are thought to be particularly vulnerable to the effects of tariffs: apparel (the blue line), toys (the red line), and motor vehicles (the green line). To make recent changes clearer, we look only at the months since January 2021. In June, prices of apparel fell, while the prices of toys and motor vehicles rose by less than 1.0 percent.

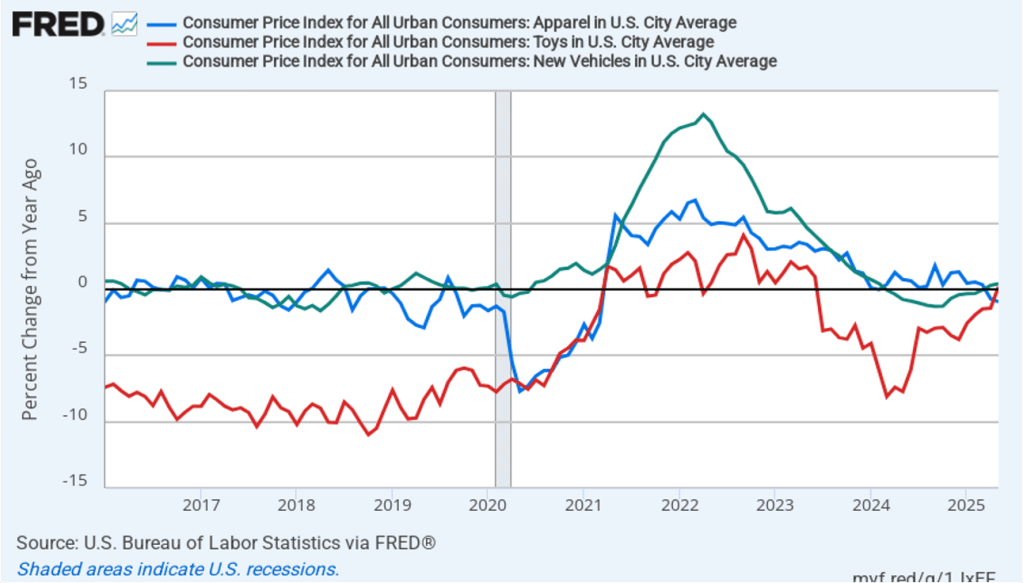

The following figure shows 1-month inflation in these prices of these products. In June, the motor vehicles prices fell, while apparel prices increased 5.3 percent and the prices of toys soared by 24.3 percent, which was the second month in a row of very large increases in toy prices.

The 1-month inflation data for these three products are a mixed bag with two of the products showing significant increases and one showing a decline. It’s likely that some of the effects of the tariffs are still being cushioned by firms increasing their inventories earlier in the year in anticipation of price increases resulting from the tariffs. As firms draw down their inventories, we may see tariff-related increases in the prices of more goods later in the year.

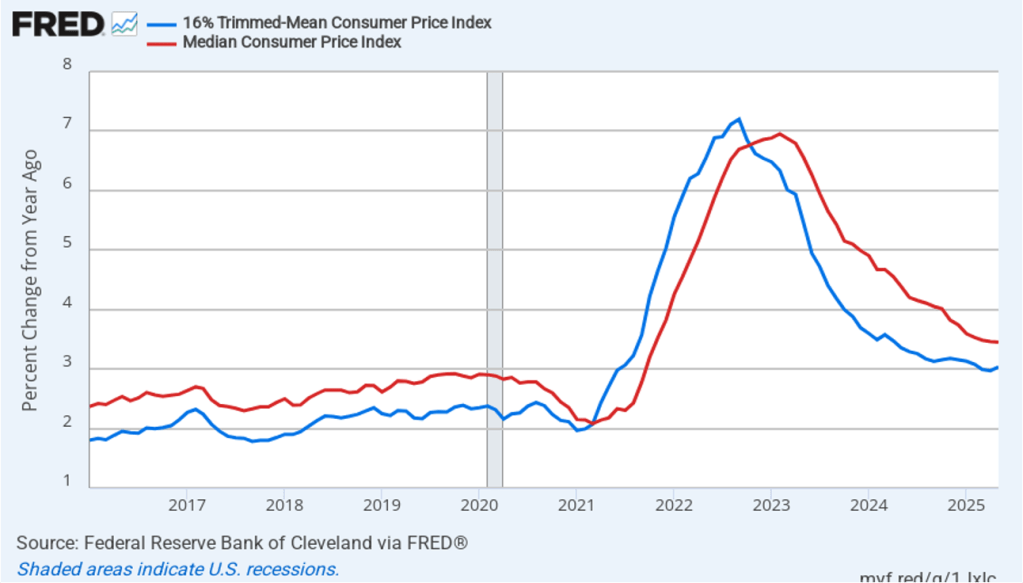

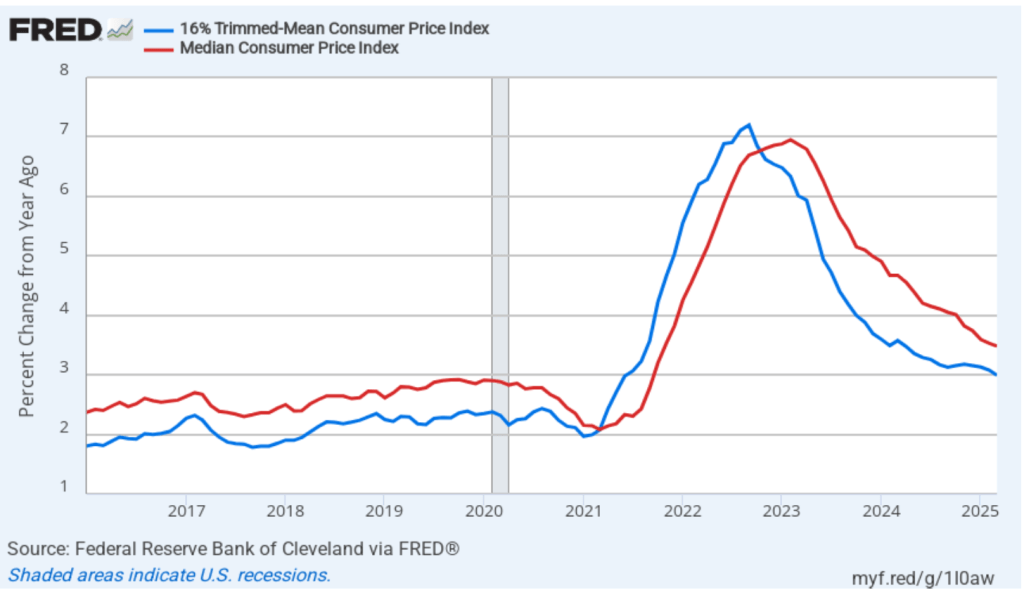

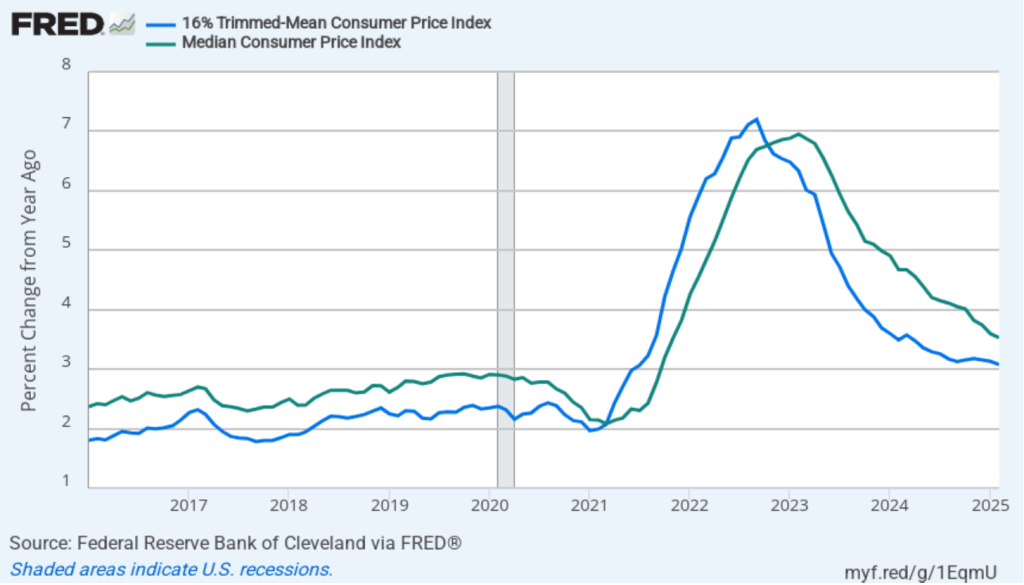

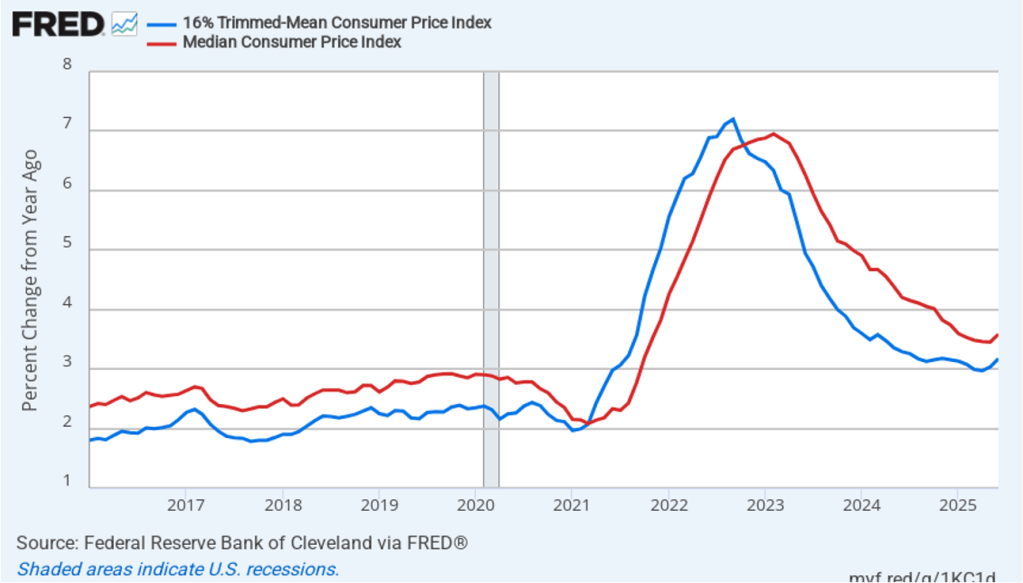

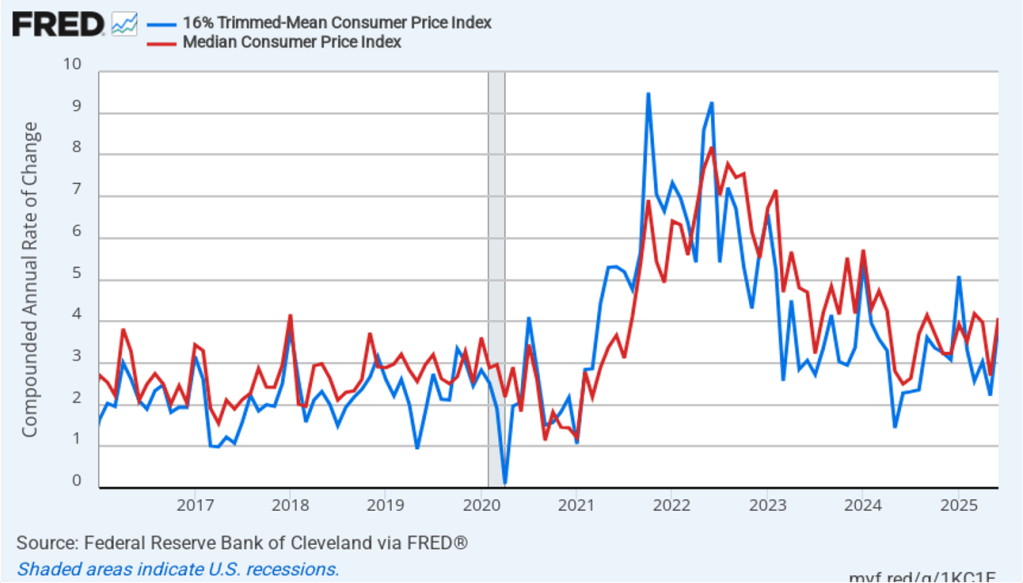

To better estimate the underlying trend in inflation, some economists look at median inflation and trimmed mean inflation.

- Median inflation is calculated by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and Ohio State University. If we listed the inflation rate in each individual good or service in the CPI, median inflation is the inflation rate of the good or service that is in the middle of the list—that is, the inflation rate in the price of the good or service that has an equal number of higher and lower inflation rates.

- Trimmed-mean inflation drops the 8 percent of goods and services with the highest inflation rates and the 8 percent of goods and services with the lowest inflation rates.

The following figure shows that 12-month trimmed-mean inflation (the blue line) was 3.2 percent in June, up from 3.0 percent in May. Twelve-month median inflation (the red line) 3.6 percent in June, up from 3.5 percent in May.

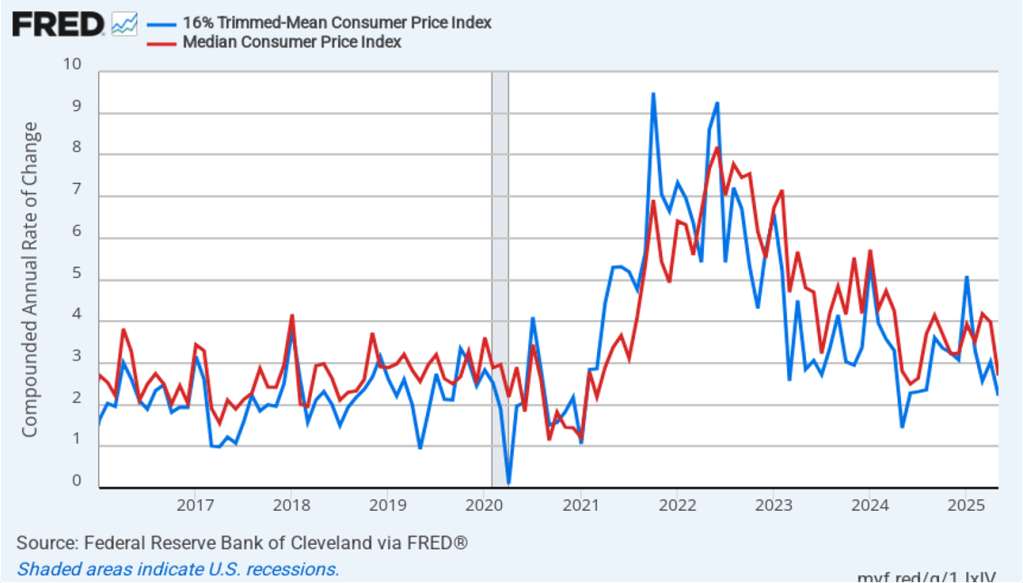

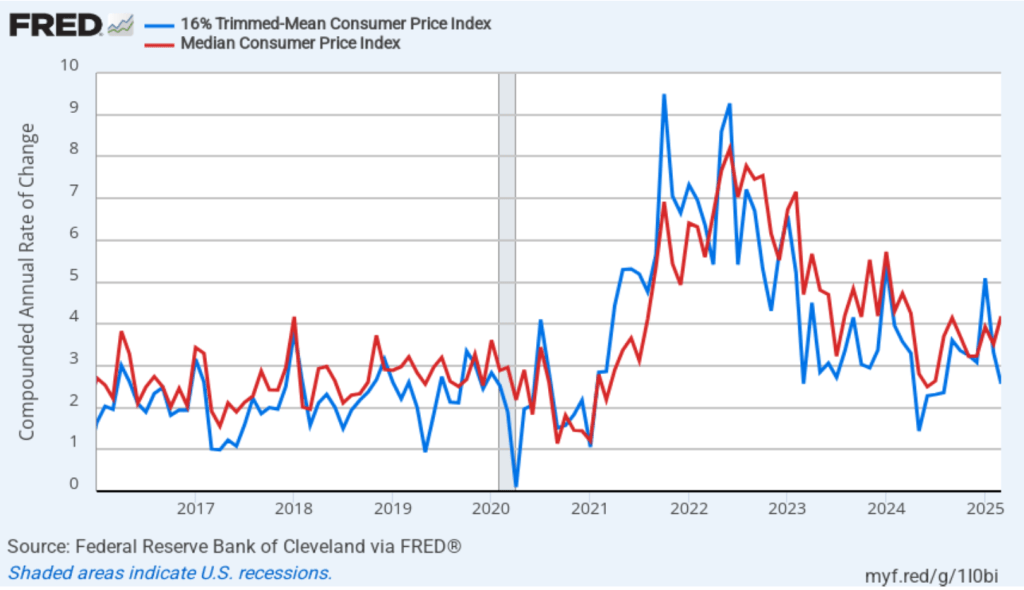

The following figure shows 1-month trimmed-mean and median inflation. One-month trimmed-mean inflation rose sharply from 2.2 percent in May to 3.9 percent in June. One-month median inflation also rose sharply from 2.7 percent in May to 4.1 percent in June. These data provide some confirmation that inflation likely rose from May to June.

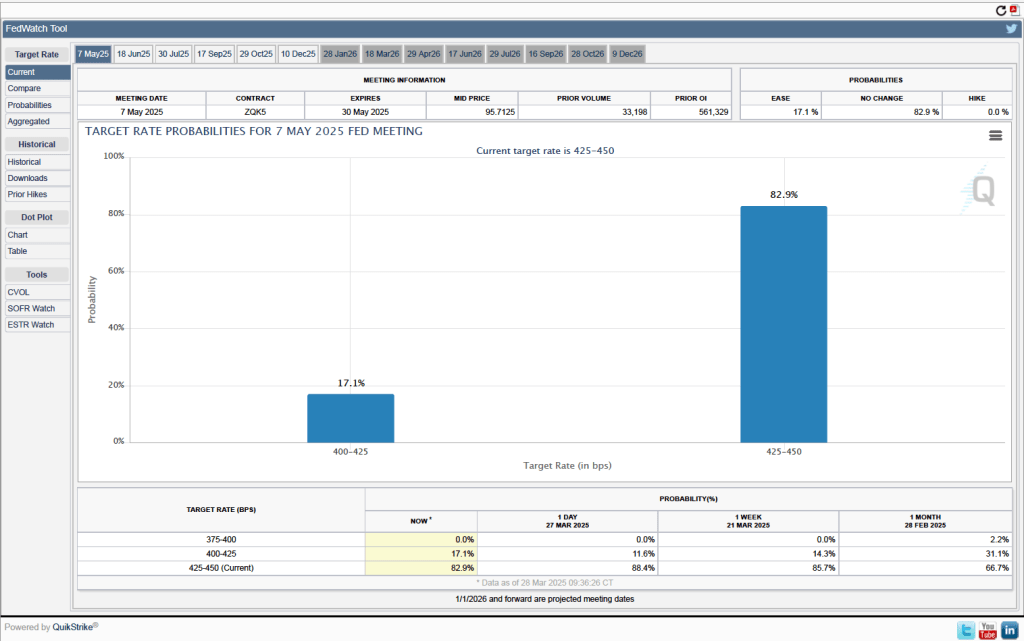

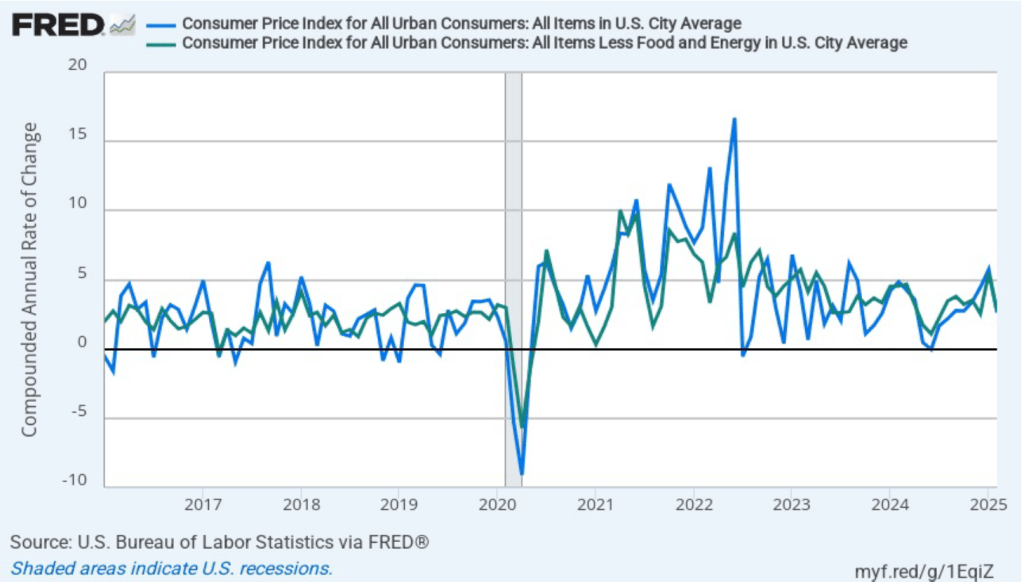

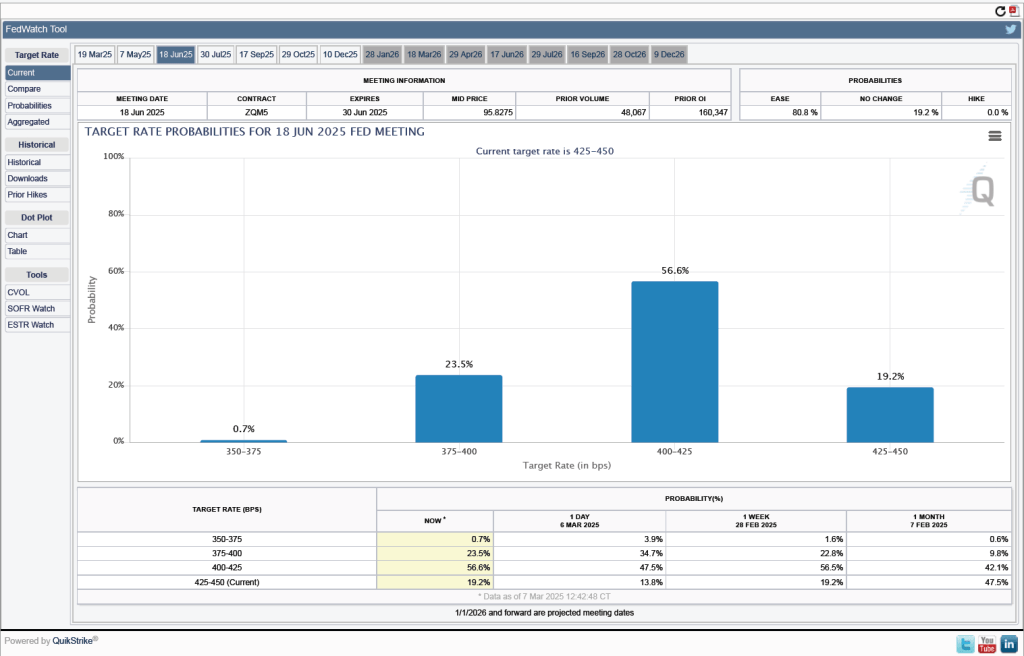

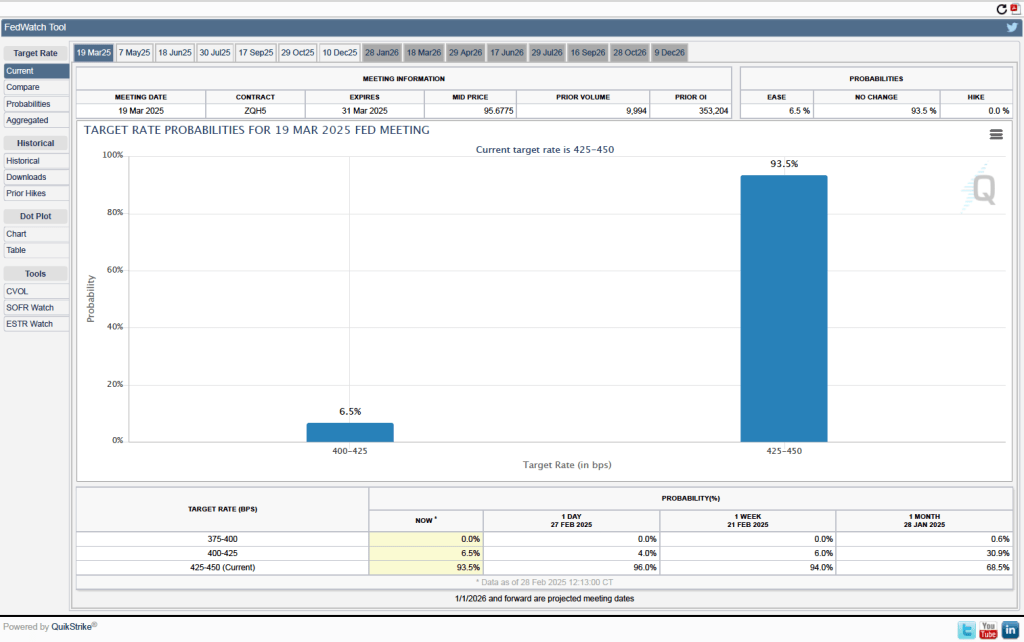

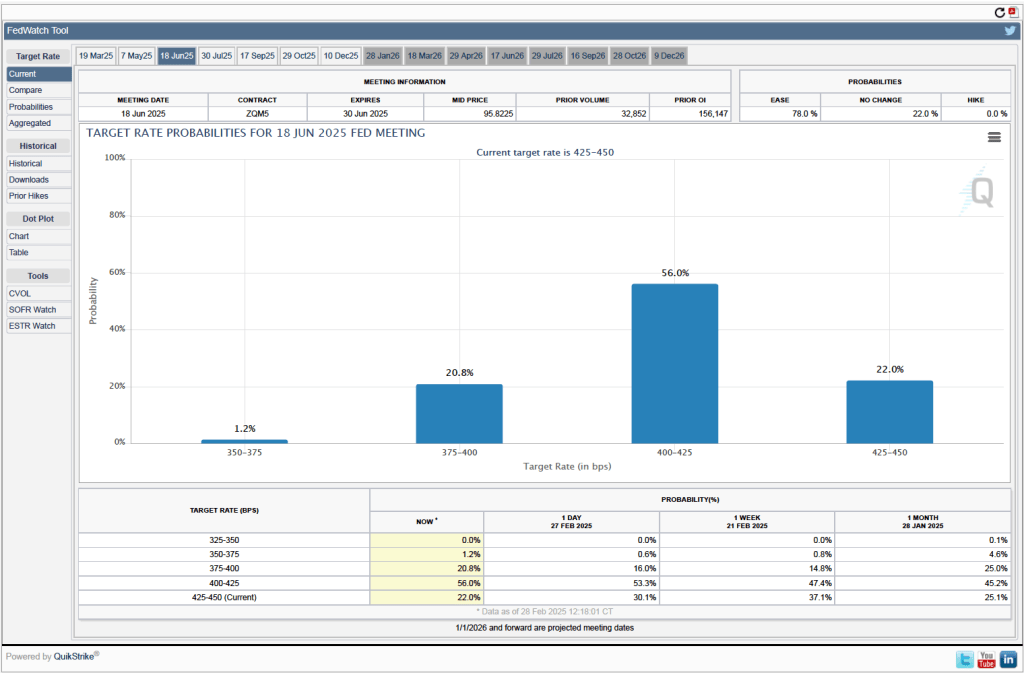

What are the implications of this CPI report for the actions the Federal Reserve’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) may take at its next meetings? Investors who buy and sell federal funds futures contracts still expect that the FOMC will leave its target for the federal funds rate unchanged at its July 29–30 meeting before cutting its target by 0.25 (25 basis points) from its current target range of 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent at its September 16–17 meeting. (We discuss the futures market for federal funds in this blog post.) The FOMC’s actions will likely depend in part on the effect of the tariff increases on the inflation rate during the coming months. If inflation were to increase significantly, it’s possible that the committee would decide to raise, rather than lower, its target range.