Join authors Glenn Hubbard and Tony O’Brien as they discuss how core economic principles illuminate two of the most pressing policy debates facing the economy today: tariffs and artificial intelligence. Drawing on a recent Supreme Court decision striking down broad tariff increases, Hubbard and O’Brien explain why economists view tariffs as taxes, who ultimately bears their burden, and how trade policy uncertainty shapes business decisions, inflation, and economic growth—bringing textbook concepts like tax incidence, intermediate goods, and GDP measurement vividly to life. The conversation then turns to AI, where they cut through market hype and dire predictions to place generative AI in historical context as a general‑purpose technology, comparing it to past innovations that transformed jobs without eliminating work. Along the way, they explore how AI can both substitute for and complement labor, why fears of mass unemployment are likely overstated, and what economists can—and cannot yet—say about AI’s long‑run effects on productivity, profits, and the labor market.

Category: Trade

NEW! 11-07-25- Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien discuss Tariffs, AI, and the Economy

Glenn Hubbard and Tony O’Brien begin by examining the challenges facing the Federal Reserve due to incomplete economic data, a result of federal agency shutdowns. Despite limited information, they note that growth remains steady but inflation is above target, creating a conundrum for policymakers. The discussion turns to the upcoming appointment of a new Fed chair and the broader questions of central bank independence and the evolving role of monetary policy. They also address the uncertainty surrounding AI-driven layoffs, referencing contrasting academic views on whether artificial intelligence will complement existing jobs or lead to significant displacement. Both agree that the full impact of AI on productivity and employment will take time to materialize, drawing parallels to the slow adoption of the internet in the 1990s.

The podcast further explores the recent volatility in stock prices of AI-related firms, comparing the current environment to the dot-com bubble and questioning the sustainability of high valuations. Hubbard and O’Brien discuss the effects of tariffs, noting that price increases have been less dramatic than expected due to factors like inventory buffers and contractual delays. They highlight the tension between tariffs as tools for protection and revenue, and the broader implications for manufacturing, agriculture, and consumer prices. The episode concludes with reflections on the importance of ongoing observation and analysis as these economic trends evolve.

Pearson Economics · Hubbard OBrien Economics Podcast – 11-06-25 – Economy, AI, & Tariffs

08-16-25- Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien discuss tariffs, Fed independence, & the controversies at the BLS.

In today’s episode, Glenn Hubbard and Tony O’Brien take on three timely topics that are shaping economic conversations across the country. They begin with a discussion on tariffs, exploring how recent trade policies are influencing prices, production decisions, and global relationships. From there, they turn to the independence of the Federal Reserve Bank, explaining why central bank autonomy is essential for sound monetary policy and what risks arise when political pressures creep in. Finally, they shed light on the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), unpacking how its data collection and reporting play a vital role in guiding both public understanding and policymaking.

It’s a lively and informative conversation that brings clarity to complex issues—and it’s perfect for students, instructors, and anyone interested in how economics connects to the real world.

Glenn Discusses Tariffs on Firing Line

Image created by ChatGTP-4o

Recently, Glenn appeared on the Firing Line program to discuss tariffs. Coincidentally, Margaret Hoover, the host of the program, is the great-granddaughter of Herbert Hoover. Herbert Hoover was the president who signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff bill in 1930. We discussed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in a recent blog post.

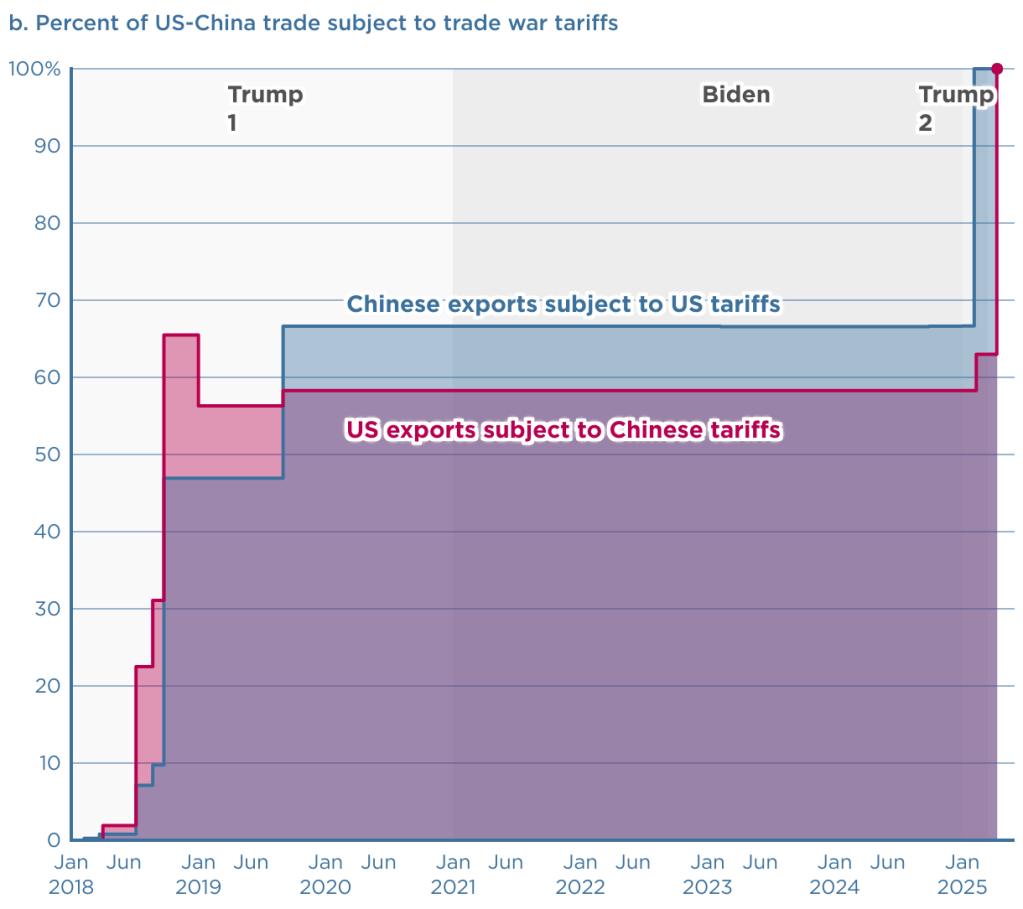

The U.S.-China Trade War Illustrated in Two Graphs from the Peterson Institute

Photo of U.S. President Donald Trump and China President Xi Jinping from Reuters.

The tit-for-tat tariff increases the U.S. and Chinese governments have levied on each other’s imports have reached dizzying heights today (April 11). The United States has imposed a tariff rate of 134.7 percent on imports from China, while China has imposed a tariff rate of 147.6 percent on imports from the United States. On all other countries—the rest of the world (ROW)—the United States imposes an average tariff rate of 10.5 percent, which is a sharp increase reflecting the Trump Administration’s imposition of a tariff of at least 10 percent on all countries. The government of China imposes a tariff rate of 6.5 percent on the ROW.

The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) is a think tank located in Washington, DC. Chad Brown, a senior fellow at PIIE, has created two charts that dramatically illustrate the current state of the U.S.-China trade war. The first chart shows the changes since the beginning of the first Trump Administration in 2017 in the tariff rates the countries have imposed on each other’s imports.

The second chart shows the percentage of each country’s exports to the other country that have been subject to tariffs. As of today, 100 percent of each country’s exports are subject to the other country’s tariffs.

Finally, we repeat a figure from an earlier blog post showing changes over time in the average tariff rate the United States levies on imports. The value for 2025 of 16.5 percent is an estimate by the Tax Foundation and assumes that the tariff rates that the Trump Administration announced on April 2 go into force, although the rates are currently suspended for 90 days—apart from those imposed on China. (An average tariff rate of 16.5 percent would be the highest levied by the United States since 1937.)

Thanks to Fernando Quijano for preparing this figure.

Douglas Irwin on Tariffs

Image generated by ChatGTP-4o illustrating tariffs.

Douglas Irwin, a professor of economics at Dartmouth College, may be the leading historian of international trade in the United States today. Irwin has posted at this link a useful overview of the economics of tariffs.

Irwin’s feed on X offers day-to-day commentary on current developments in the Trump Administration’s rapidly changing tariff policies. At the top of his X feed, you can find a free download of Clashing over Commerce, his 2019 history of U.S. foreign trade policy. At 862 pages, the book is the most thorough and comprehensive account available of the long-running political disputes in the United States over foreign trade.

03/29/25 Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien discuss the impact of tariffs on monetary policy & the Fed.

Please listen to a podcast discussion recorded just this past Friday between Glenn Hubbard and Tony O’Brien as they discuss tariffs and it’s impact on monetary policy. Also, check out the regular blog posts while on the site! So much has been happening and these posts helps both instructors and students integrate this discussion into their classroom.

Join authors Glenn Hubbard and Tony O’Brien as they discuss the impact of new tariff policies on trade but also on the larger economy. They delve into the Fed, monetary policy, and the impact on inflation. They also discuss some of the history back to when tariffs used to be a high proportion of government revenue and analyze the mix of products that are imported & exported by the US. Should the Fed change its current behavior due to the tariff environment?

https://on.soundcloud.com/PNi5sLLkC4GikoX1AGlenn and Catherine Wolfram Propose a New Tool in Bargaining with Russia

Image generated by ChatGTP-4o

How to Punish Russia, Make Money and End the War

Even though Russia and Ukraine were engaged in cease-fire talks with American representatives in Saudi Arabia, apparently with some progress on Tuesday, President Vladimir Putin of Russia has shown little actual commitment to ending his war.

President Trump needs some better cards.

Several weeks ago, the president floated the idea of sanctions and tariffs over Russian imports. But the Kremlin has been dismissive — mainly because the United States imports very little from Russia. Extensive financial and trade sanctions have been in place, most of them for around three years, and they are plainly not enough to bring peace.

Fortunately, there is a simple way to improve the American hand. The administration should impose sanctions on any company or individual — in any country — involved in a Russian oil and gas sale. Russia could avoid these so-called secondary sanctions by paying a per shipment fee to the United States Treasury. The payment would be called a Russian universal tariff, and it would start low but increase every week that passes without a peace deal.

Ships carry most Russian oil and gas to world markets. The secondary sanctions — if Russia does not make the required payments — would fall on all parties to the transaction, including the oil tanker owner, the insurer and the purchaser. Recent evidence confirms that Indian and Chinese entities — whose nations import considerable oil from Russia and have not imposed their own penalties on the Russian economy over the war in Ukraine — do not want to be caught up in American sanctions, making this idea workable. Another factor in its favor: All such tanker traffic is tracked carefully by commercial parties and by U.S. authorities.

Secondary sanctions are powerful tools: Violators can be cut off from the U.S. financial system, and they apply even to transactions that don’t directly involve American companies. They have been used to limit Iranian oil exports and to require that payments for Iranian oil be held in restricted accounts until sanctions were lifted. Our proposal would take this approach to another level. Under our plan, a portion of each Russian oil and gas sale would be paid to the U.S. Treasury until Russia agrees to a peace deal. The goal is to keep Russian oil flowing to global markets but with less money going to the Kremlin. The plan would sap Russia’s ability to continue waging war, and it puts money into U.S. government coffers.

In Russia, fossil fuel revenues and military spending are intertwined, although the country can also draw on its sovereign wealth fund and other sources. Fossil fuel exports provide the main source of dollar revenue for the Kremlin, which depends on hard currency to buy arms and other military supplies from abroad and pay for North Korean soldiers. The country currently exports about $500 million worth of crude oil and petroleum products and $100 million worth of natural gas every day. The Kremlin budgeted a slightly lower amount, almost $400 million per day for military spending in 2025.

The Russia universal tariff would provide money for the United States immediately, unlike the proposed Ukrainian critical minerals fund, which would take years to generate any returns. A fee of $20 per barrel of oil could generate up to $120 million per day (more than $40 billion per year), with additional revenue available if a similar fee is imposed on natural gas. Every dollar the United States collects is a dollar that Russia can’t spend to fund its war.

Ideally, the policy would pressure Russia into negotiations, where its removal could be part of a deal. If not, the United States would still collect billions annually, which could help fund Mr. Trump’s proposed tax cuts. In that scenario, Russia would effectively be helping repay the U.S. tax dollars used to provide aid to Ukraine to defend itself against Russia’s assault.

For the past three years, Western sanctions and public outcry, including some dockworkers’ refusal to unload Russian oil tankers, have forced Russia to search for new buyers and sell its oil at a discount compared with global prices. The oil discount averaged about $9 per barrel over the previous 12 months and was as high as $35 per barrel in April 2022. Despite receiving lower prices for its oil, Russia has maintained export volumes, ensuring a steady supply in the global oil market.

By imposing secondary sanctions unless the Russia universal tariff is paid, the United States would be taking a cut of the revenues, effectively increasing the discount on Russian oil. Russia’s continued exports, despite facing large discounts over the past three years, suggest it would continue exporting the same volume. That would keep global oil supply stable and help keep oil prices in check. Oil and gas in Russia are inexpensive to produce, and it relies heavily on the income they generate, so it has little option but to keep selling, even at lower prices.

While Mr. Trump can adopt this strategy, Congress can strengthen his negotiating position by passing a bill that puts the Russia universal tariff in place on its own. That would allow the president to protect his lines of communication with Mr. Putin by blaming the measure on Congress. He would also determine if and when he wants to sign the bill, giving him additional leverage over Russia. It’s possible the mere discussion of such a bill could help push the Kremlin toward a peace deal.

Combining secondary sanctions, a strong tool in the U.S. economic kit, with a tarifflike fee could pressure Mr. Putin by threatening his most valuable source of revenues. It would also make it easier for Mr. Trump to deliver on his promise of a lasting peace.

Catherine Wolfram, a former deputy assistant secretary for climate and energy in the Treasury Department, is a professor at M.I.T.’s Sloan School of Management.

This op-ed first appeared in the New York Times.

A Brief Overview of Tariffs

Image generated by GTP-4o

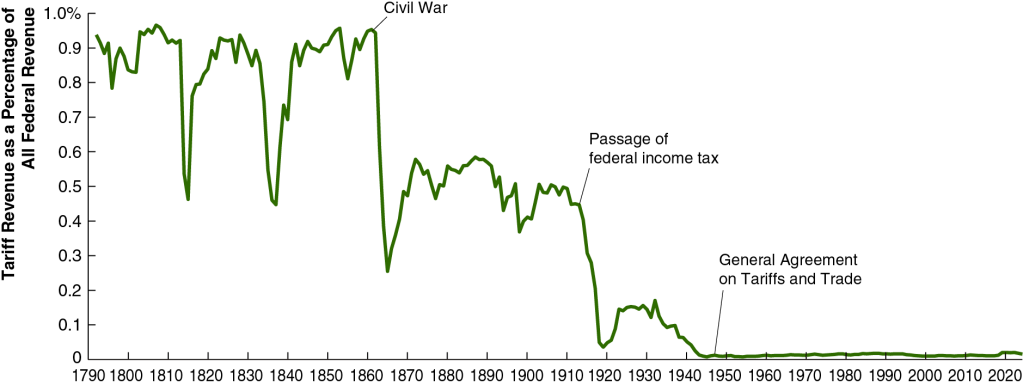

A tariff is a tax a government imposes on imports. Since the end of World War II, high-income countries have only occasionally used tariffs as an important policy tool. The following figure shows how the average U.S. tariff rate, expressed as a percentage of the value of total imports, has changed in the years since 1790. The ups and downs in tariff rates reflect in part political disa-greements in Congress. Generally speaking, through the early twentieth century, members of Congress who represented areas in the Midwest and Northeast that were home to many manufacturing firms favored high tariffs to protect those industries from foreign competition. Members of Congress from rural areas opposed tariffs, because farmers were primarily exporters who feared that foreign governments would respond to U.S. tariffs by imposing tariffs on U.S. agricultural exports. From the pre-Civil War period until after World War II the Republicans Party generally favored high tariffs and the Democratic Party generally favored low tariffs, reflecting the economic interests of the areas the parties represented in Congress. (Note: Because the tariffs that the Trump Administration will end up imposing are still in flux, the value for 2025 in the figure is only a rough estimate.)

By the end of World War II in 1945, government officials in the United States and Europe were looking for a way to reduce tariffs and revive international trade. To help achieve this goal, they set up the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1948. Countries that joined the GATT agreed not to impose new tariffs or import quotas. In addition, a series of multilateral negotiations, called trade rounds, took place, in which countries agreed to reduce tariffs from the very high levels of the 1930s. The GATT primarily covered trade in goods. A new agreement to cover services and intellectual property, as well as goods, was eventually negotiated, and in January 1995, the GATT was replaced by the World Trade Organization (WTO). In 2025, 166 countries are members of the WTO.

As a result of U.S. participation in the GATT and WTO, the average U.S. tariff rate declined from nearly 20% in the early 1930s to 1.8% in 2018. The first Trump Administration increased tariffs beginning in 2018, raising the average tariff rate to 2.5%. (The Biden Administration continued most of the increases.) In 2025, the second Trump Administration’s substantial increases in tariffs raised the average tariff rate to the highest level since the 1940s.

Until the enactment in 1913 of the 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which allowed for a federal income tax, tariffs were an important source of revenue to the federal government. As the following figure shows, in the early years of the United States, more than 90% of federal government revenues came from the tariff. As tariff rates declined and federal income and payroll taxes increased, tariffs declined to only 2% of federal government revenue. It’s unclear yet how much tariff’s share of federal government revenue will rise as a result of the Trump Administration’s tariff increases.

The effect of tariff increases on the U.S. economy are complex and depend on the details of which tariffs are increased, by how much they are increased, and whether foreign governments raise their tariffs on U.S. exports in response to U.S. tariff increases. We can analyze some of the effects of tariffs using the basic aggregate demand and aggregate supply model that we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 13 (Economics, Chapter 23). We need to keep in mind in the following discussion that small increases in tariffs rates—such as those enacted in 2018—will likely have only small effects on the economy given that net exports are only about 3% or U.S. GDP.

An increase in tariffs intended to protect domestic industries can cause the aggregate demand curve to shift to the right if consumers switch spending from imports to domestically produced goods, thereby increasing net exports. But this effect can be partially or wholly offset if trading partners retaliate by increasing tariffs on U.S. exports. When Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in 1930, which raised tariff rates to historically high levels, retaliation by U.S. trading partners contributed to a sharp decline in U.S. exports during the early 1930s.

International trade can increase a country’s production and income by allowing a country to specialize in the goods and services in which it has a comparative advantage. Tariffs shift a country’s allocation of labor, capital, and other resources away from producing the goods and services it can produce most efficiently and toward producing goods and services that other countries can produce more efficiently. The result of this misallocation of resources is to reduce the productive capacity of the country, shifting the long-run aggregate supply curve (LRAS) to the left.

Tariffs raise the prices of U.S. imports. This effect can be partially offset because tariffs increase the demand for U.S. dollars relative to trading partners’ currencies, increasing the dollar exchange rate. Because a tariff effectively acts as a tax on imports, like other taxes its incidence—the division of the burden of the tax between sellers and buyers—depends partly on the price elasticity of demand and the price elasticity of supply, which vary across the goods and services on which tariffs are imposed. (We discuss the effects of demand and supply elasticity on the incidence of a tax in Microeconomics, Chapter 17, Section 17.3.)

About two-thirds of U.S. imports are raw materials, intermediate goods, or capital goods, all of which are used as inputs by U.S. firms. For example, many cars assembled in the United States contain imported parts. The popular Ford F-Series pickup trucks are assembled in the United States, but more than two-thirds of the parts are imported from other countries. That fact indicates that the automobile industry is one of many U.S. industries that depend on global supply chains that can be disrupted by tariffs. Because tariffs on imported raw materials, parts and other intermediate goods, and capital goods increase the production costs of U.S. firms, tariffs reduce the quantity of goods these firms will produce at any given price. In terms of the aggregate demand and aggregate supply model , a large unexpected increase in tariffs results in an aggregate supply shock to the economy, shifting the short-run aggregate supply curve (SRAS) to the left.

Our thanks to Fernando Quijano for preparing the two figures.

1/17/25 Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien discuss the pros/cons of tariffs and the impact of AI on the economy.

Welcome to the first podcast for the Spring 2025 semester from the Hubbard/O’Brien Economics author team. Check back for Blog updates & future podcasts which will happen every few weeks throughout the semester.

Join authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien as they offer thoughts on tariffs in advance of the beginning of the new administration. They discuss the positive and negative impacts of tariffs -and some of the intended consequences. They also look at the AI landscape and how its reshaping the US economy. Is AI responsible for recent increased productivity – or maybe just the impact of other factors. It should be looked at closely as AI becomes more ingrained in our economy.

https://on.soundcloud.com/8ePL8SkHeSZGwEbm8