An image generated by ChatGTP-4o of a hypothetical meeting between President Richard Nixon and Fed Chair Arthur Burns in the White House.

In a speech on April 15 at the Economic Club of Chicago, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell discussed how the Fed might react to President Donald Trump’s tariff increases: “Tariffs are highly likely to generate at least a temporary rise in inflation. The inflationary effects could also be more persistent…. Our obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored and to make certain that a one-time increase in the price level does not become an ongoing inflation problem.”

Powell’s remarks were interpreted as indicating that the Fed’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) was unlikely to cut its target for the federal funds rate anytime soon. President Trump, who has stated several times that the FOMC should cut its target, was displeased with Powell’s position and posted on social media that “Powell’s termination cannot come fast enough!” Stock prices declined sharply on the possibility that Trump might try to fire Powell because many economists and market participants believed that move would increase uncertainty and possibly undermine the FOMC’s continuing attempts to bring inflation down to the Fed’s 2 percent target. Trump, possibly responding to the fall in stock prices, stated to reporters that he had “no intention” of firing Powell. In this recent blog post we discuss the debate over whether presidents can legally fire Fed chairs.

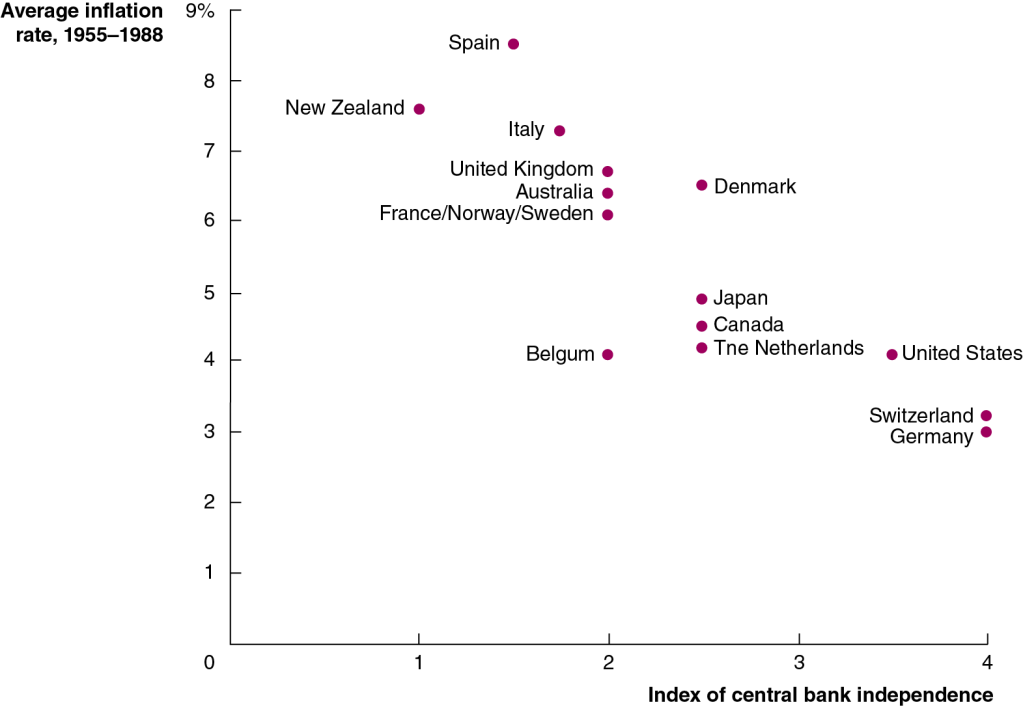

Leaving aside the legal issue of whether a president can fire a Fed chair, would it be better or worse for the conduct of monetary if the presdient did have that power? We review the arguments for and against the Fed conducting monetary policy independently of the president and Congress in Macroeconomics, Chapter 17, Section 17.4 (Economics, Chapter 27, Section 27.4). One key point that’s often made in favor of Fed independence is illustrated in Figure 17.12, which is reproduced below.

The figure is from a classic study by Alberto Alesina and Lawrence Summers, who were both economists at Harvard University at the time. Alesina and Summers tested the assertion that the less independent a country’s central bank, the higher the country’s inflation rate will be by comparing the degree of central bank independence and the inflation rate for 16 high-income countries during the years from 1955 to 1988. As the figure shows, countries with highly independent central banks, such as the United States, Switzerland, and Germany, had lower inflation rates than countries whose central banks had little independence, such as New Zealand, Italy, and Spain. In the following years, New Zealand and Canada granted their banks more independence, at least partly to better fight inflation.

Debates over Fed independence didn’t start with President Trump and Fed Chair Powell; they date all the way back to the passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. The background to the passage of the Act is the political struggle over establishing a central bank during the early years of the country. In 1791, Congress established the Bank of the United States, at the urging of the country’s first Treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton. When the bank’s initial 20-year charter expired in 1811, political opposition kept the charter from being renewed, and the bank went out of existence. The bank’s opponents believed that the bank’s actions had the effect of reducing loans to farmers and owners of small businesses and that Congress had exceeded its constitutional authority in establishing the bank. Financial problems during the War of 1812 led Congress to charter the Second Bank of the United States in 1816. But, again, political opposition, this time led by President Andrew Jackson, resulted in the bank’s charter not being renewed in 1836.

As we discuss in Chapter 14, Section 14.4, Congress established the Federal Reserve as a lender of last resort to bring an end to bank panics. In 1913, Congress was less concerned aboout making the Fed independent from Congress and the president than it was in overcoming political opposition to establishing a central bank located in Washington, DC. Accordingly, Congress established a decentralized system by having 12 District Banks that would be owned by the member banks in the district. Congress gave the responsibility for overseeing the system to the Federal Reserve Board, which was the forerunner of the current Board of Governors. The president had a greater influence on the Federal Reserve Board than presidents today have on the Board of Governors because the Federal Reserve Board included the secretary of the Treasury and the comptroller of the currency as members. Then as now, the president is free to replace the secretary of the Treasury and the comptroller of the currency at any time.

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the Fed came under pressure to help the Treasury finance the war by making loans to banks to help the banks purchase Treasury securities—Liberty Bonds—and by lending funds to banks that banks could loan to households to purchase bonds. In 1919, a ruling by the attorney general clarified that Congress had intended in the Federal Reserve Act to give the Federal Reserve Board the power to set the discounts rate the 12 District Banks charged member banks on loans.

Despite this ruling, authority within the Fed remained much more divided than is true today. Divided authority proved to be a serious problem when the Fed had to deal with the Great Depression, which began in August 1929 and worsened as the result of a series of bank panics. As we’ve seen, the secretary of the Treasury and the comptroller of the currency, both of whom report directly to the president of the United States, served on the Federal Reserve Board. So, the Fed had less independence from the executive branch of the government than it does today.

In addition, the heads of the 12 District Banks operated much more independently than they do today, with the head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York having nearly as much influence within the system as the head of the Federal Reserve Board. At the time of the bank panics, George Harrison, the head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, served as chair of the Open Market Policy Conference, the predecessor of the current Federal Open Market Committee. Harrison frequently acted independently of Roy Young and Eugene Meyer, who served as heads of the Federal Reserve Board during those years. Important decisions could be made only with the consensus of these different groups. During the early 1930s, consensus proved hard to come by, and taking decisive policy actions was difficult.

The difficulties the Fed had in responding to the Great Depression led Congress to reorganize the system with the passage of the Banking Act of 1935. Most of the current structure of the Fed was put in place by that law. Power was concentrated in the hands of the Board of Governors. The removal of the secretary of the Treasury and the comptroller of the currency from the Board reduced the ability of the president to influence the Fed’s decisions.

During World War II, the Fed again came under pressure to help the federal government finance the war. The Fed agreed to hold interest rates on Treasury securities at low levels: 0.375% on Treasury bills and 2.5% on Treasury bonds. The Fed could keep interest rates at these low levels only by buying any bonds that were not purchased by private investors, thereby fixing, or pegging, the rates.

When the war ended in 1945, the Treasury and President Harry Truman wanted to continue this policy, but the Fed didn’t agree. The Fed’s concern was inflation: Larger purchases of Treasury securities by the Fed could increase the growth rate of the money supply and the rate of inflation. Fed Chair Marriner Eccles strongly objected to the policy of fixing interest rates. His opposition led President Truman to not reappoint him as chair in 1948,although Eccles continued to fight for Fed independence during the remainder of his time as a governor. On March 4, 1951, the federal government formally abandoned the wartime policy of fixing the interest rates on Treasury securities with the Treasury–Federal Reserve Accord. This agreement was important in eestablishing the Fed’s ability to operate independently of the Treasury.

Conflicts between the Treasury and the Fed didn’t end with that agreement, however. Thomas Drechsel of the University of Maryland has analyzed the daily schedules of presidents during the period from 1933 to 2016 and finds that during these years presidents met with Fed officials on more than 800 occasions. Of course, not all of these interactions involved attempts by a president to influence the actions of a Fed Chair, but some seem to have. For example, research by Helen Fessenden of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond has shown that in 1967, President Lyndon Johnson, who was facing reelection in 1968, was anxious that Fed Chair William McChesney Martin adopt a more expansionary monetary policy. There is some evidence that Johnson and Martin came to an agreement that if Johnson agreed to push Congress to increase taxes, Martin would pursue an expansionary monetary policy.

An image generated by ChatGTP-4o of a hypothetical meeting between President Lyndon Johnson and Fed Chair William McChesney Martin in the White House.

Similarly, in late 1971, President Richard Nixon was concerned that the unemployment rate was at 6%, which he believed would, if it persisted, endanger his chance of reelection in 1972. Dreschel finds that Nixon met with Fed Chair Arthur Burns 34 times during the second half of 1971. Evidence from tape recordings of Nixon’s conversations with Burns at the White House and from Burns’s diary entries indicate that Nixon pressured Burns to increase the rate of growth of the money supply and that Burns agreed to do so.

President Ronald Reagan and Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker argued over who was at fault for the severe economic recession of the early 1980s. Reagan blamed the Fed for soaring interest rates. Volcker held that the Fed could not take action to bring down interest rates until the budget deficit—which results from policy actions of the president and Congress—was reduced. Similar conflicts occurred during the administrations of George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, with the Treasury frequently pushing for lower short-term interest rates than the Fed considered advisable.

During the financial crisis of 2007–2009 and during the 2020 Covid pandemic, the Fed worked closely with the Treasury. The relationship was so close, in fact, that some economists and policymakers worried that the Fed might be sacrificing some of its independence. The frequent consultations between Fed Chair Ben Bernanke and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson in the fall of 2008, during the height of the crisis, were a break with the tradition of Fed chairs formulating policy independently of a presidential administration. During the 2020 pandemic, Fed Chair Jerome Powell and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin also frequently consulted on policy.

These examples from the Fed’s history indicate that presidents have persistently attempted to influence Fed policy. Most economists believe that central bank independence is an important check on inflation. But, given the importance of monetary policy, it’s probably inevitable that presidents and members of Congress will continue to attempt to sway Fed policy.