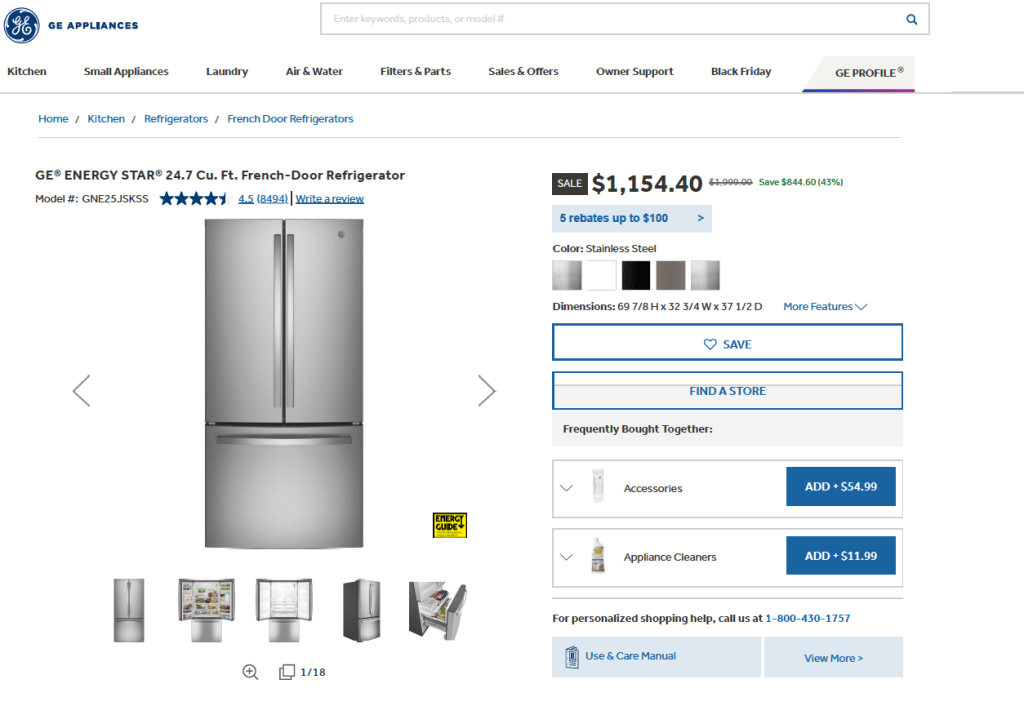

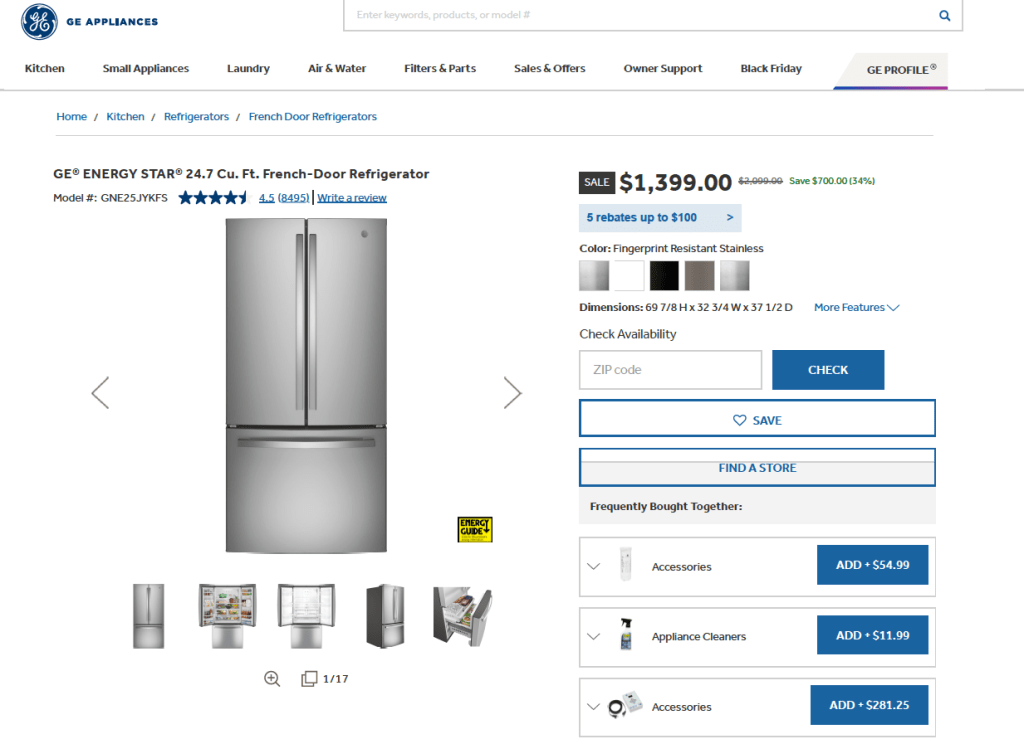

Is the refrigerator above different from the refrigerator below?

Consumer Reports is a magazine and web site devoted to product reviews. Their November-December 2024 issue noted something unusual about the two GE refrigerators shown above. (The images are from the geappliances.com web site.) At the time the issue was printed, the first refrigator above had a price of $2,300 and the second refrigerator had a price of $1,300: Consumer Reports notes that:

“These look-alike fridges offer equally impressive performance, have the same interior features … and are from the same brand. So why the $1,000 price difference? We don’t know.”

(Note: GE referigators, and many other products branded with the GE name are no longer produced by the General Electric company, which dates back to 1892 and was co-founded by Thomas Edison. Today, GE is primarily an aerospace company and GE appliances are produced by the Chinese-owned Haier Smart Home Company.)

If we assume that Consumer Reports is correct and the two refrigerators are identical, what strategy is the firm pursuing by charging different prices for the same product? As we discuss in Microeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 firms can increase their profits by practicing price discrimination—charging different prices to different customers. To pursue a strategy of price discrimination the firm needs to be able to divide up—or segment—the market for its refrigerators.

Firms sometimes use a high price to signal quality. The old saying “you get what you pay for” can lead some consumers to expect that when comparing two similar goods, such as two models of refrigerators, the one with the higher price also has higher quality. In the appliance section of a large store, such as Lowe’s or the Home Depot, or online at Amazon or another site, you will have a wide variety of refrigerators to choose from. You may have trouble evaluating the features each model offers and be unable to tell whether a particular model is likely to be more or less reliable. So, if you are choosing between the two GE models shown above, you may decide to choose the one with the higher price because the higher price may indicate that the components used are of higher quality.

In this case, GE may be relying on a segmentation in the market between consumers who carefully research the features and the quality of the refrigerators that different firms offer for sale and those consumers don’t. The consumers who do careful research and are aware of all the features of each model may be more sensitive to the price and, therefore, have a high price elasticity of demand. The consumers who haven’t done the research may be relying on the price as a signal of quality and, therefore, have a lower price elasticty of demand.

If what we have just outlined was the firm’s strategy for increasing profit by charging different prices for two models that are, apparently, either identical or very similar, it doesn’t seem to have worked. Note that the model shown in the first photo above is the one that had a price of $2,300 when Consumer Reports wrote about it, but now has a price of $1,154.40. The model shown in the second photo had a price of $1,300, but now has a price of $1,399.00. In other words, the model that had the lower price now has the higher price and the model that had the higher price now has the lower price.

What happened between the time the issue of Consumer Reports published and now? We might conjecture that there are few consumers who would be likely to pay $1,000 more for a refrigator that seems to have the same features as another model from the same company. In other words, segmenting consumers in this way seems unlikely to succeed. Why, though, the firm decided to make its formerly higher-price model its lower-price model, is difficult to explain without knowing more about the firm’s pricing strategy.