Map from the Wall Street Journal.

Supports: Microeconomics and Economics Chapter 6, Section 6.2 and Esstentials of Economics, Chapter 7, Section 7.6.

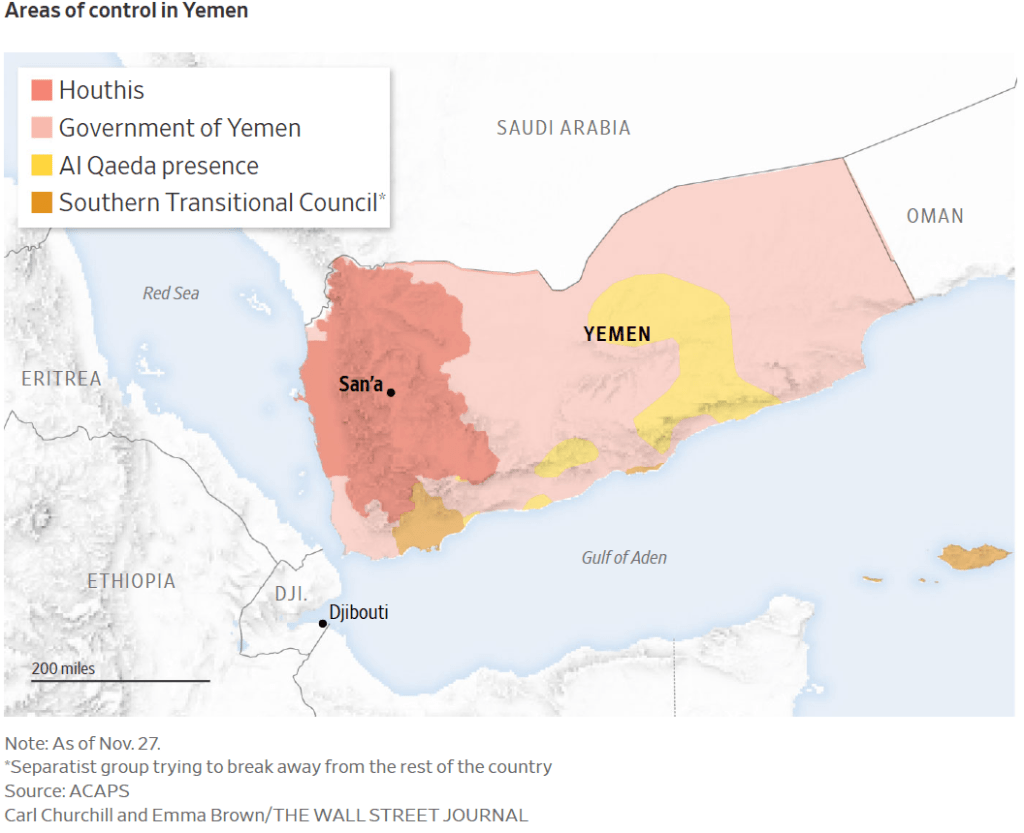

The Houthis, a rebel group based in Yemen, have been attacking shipping in the Red Sea, which freighters sail through after exiting the Suez Canal. About 30 percent of global shipping travels through the Suez Canal. An article in the Financial Times noted that maritime insurance firms have increased their charges for insuring freight passing through the Suez Canal by about $6,000 per container.” The article also noted that: “Freight demand is price inelastic in the short run and transport isn’t a big part of overall costs.” And that “the average container holds about $100,000 worth of goods wholesale, which will be sold at destination for $300,000.”

- Is there a connection between the observation that freight demand is price inelastic and the observation that the charge for transporting goods isn’t a large fraction of the price of the goods shipped by container? Briefly explain.

- The article notes that the main alternative to transporting freight by ship is to transport it by air, but if only 1 percent of freight sent by ship were to be sent by air instead, all the available flight capacity would be filled. Does this fact also have relevance to explaining the price inelasticity of demand for transporting freight by ship? Briefly explain.

Solving the Problem

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about the determinants of the price elasticity of demand, so you may want to review Microeconomics and Economics, Chapter 6, Section 6.2 (Essentials of Economics, Chapter 7, Section 7.6), “The Determinants of the Price Elasticity of Demand and Total Revenue.”

Step 2: Answer part a. by explaining why the small fraction that transportation is of the total price of the goods in a container of freight makes it more likely that the demand for shipping is price inelastic in the short run. This section of the chapter notes that goods and services that are only a small fraction of a consumer’s budget tend to have less elastic demand than do goods and services that are a large faction. In this case, the consumer is a firm shipping freight. Because the $6,000 increase per container in the cost of shipping freight makes up only 2 percent of the dollar amount the freight can be sold for, shippers are likely not to significantly reduce the quantity of shipping services they demand. Note, though, that the article refers to the price elasticity of freight demand “in the short run.” It’s possible that over a longer period of time the market for transporting freight by ship may adjust by, for instance, firms offering to ship freight by air increasing their capacity and lowering their prices. In that case, the price elasticity of demand for transporting freight by ship will be higher in the long run than in the short tun.

Step 3: Answer part b. by explaining whether the limited amount of available capacity for sending freight by air may help explain why the demand for sending freight by ship is price inelastic. This section of the chapter notes that the most important determinant of the price elasticity of demand for a good or service is the availability of close substitutes. That there is only a small amount of unused capacity to transport goods by air indicates that transporting goods by air is not a close substitute for transporting goods by sea. Therefore, we would expect that this factor contributes to the demand for transporting goods by sea being price inelastic in the short run.