Supports: Microeconomics and Economics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5, and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 10, Section 10.5

Image generated by ChatGTP 03

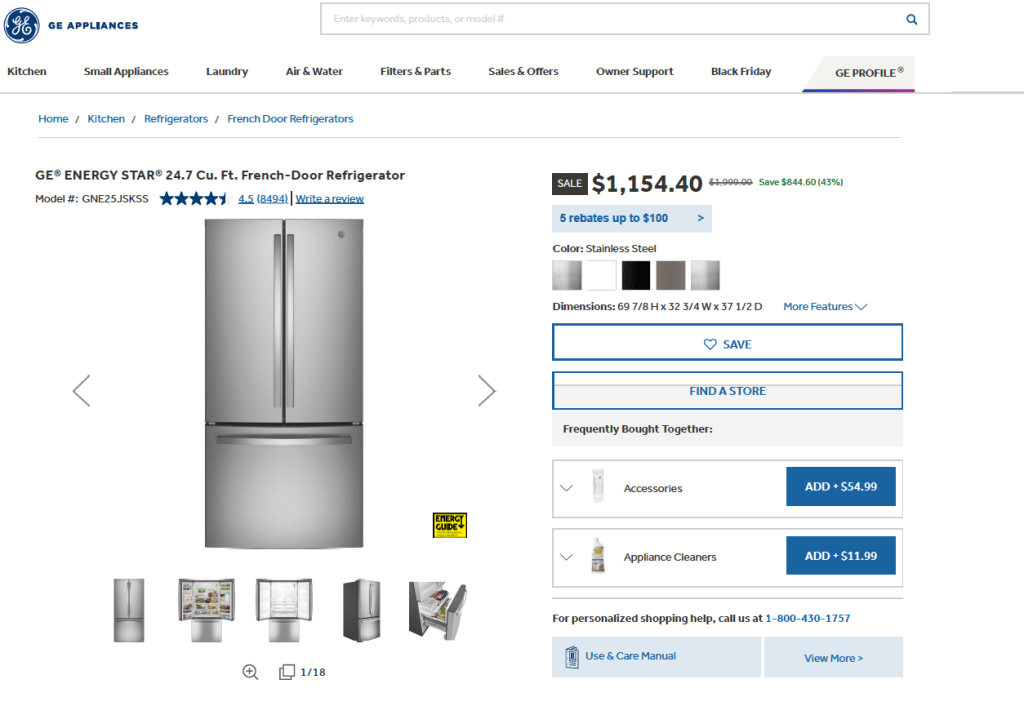

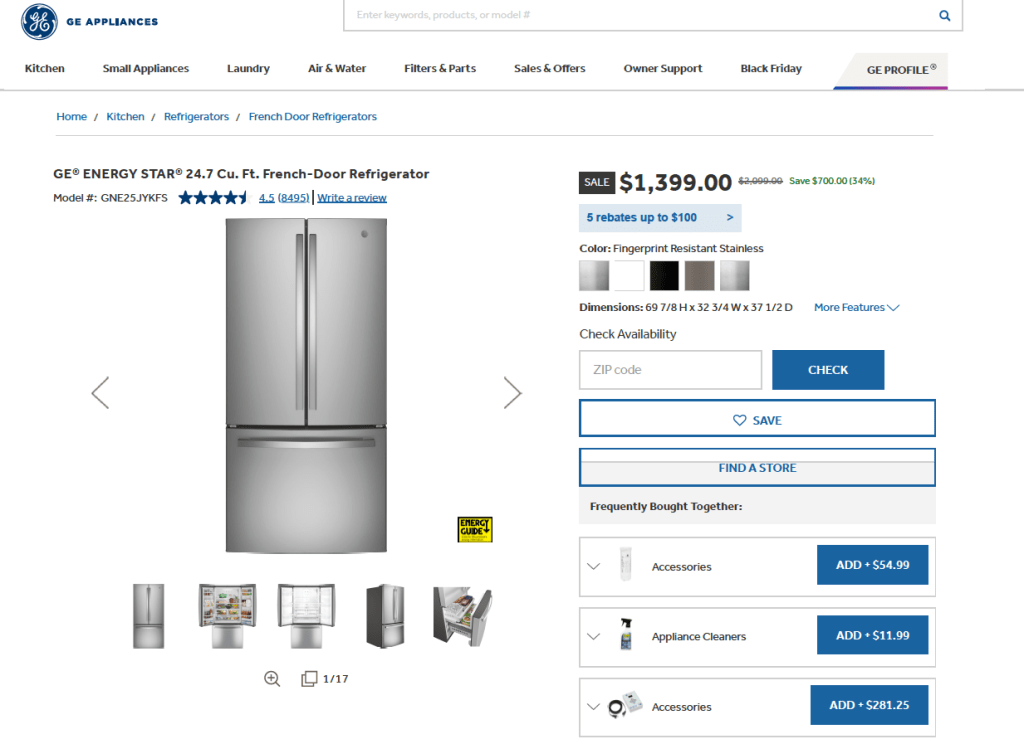

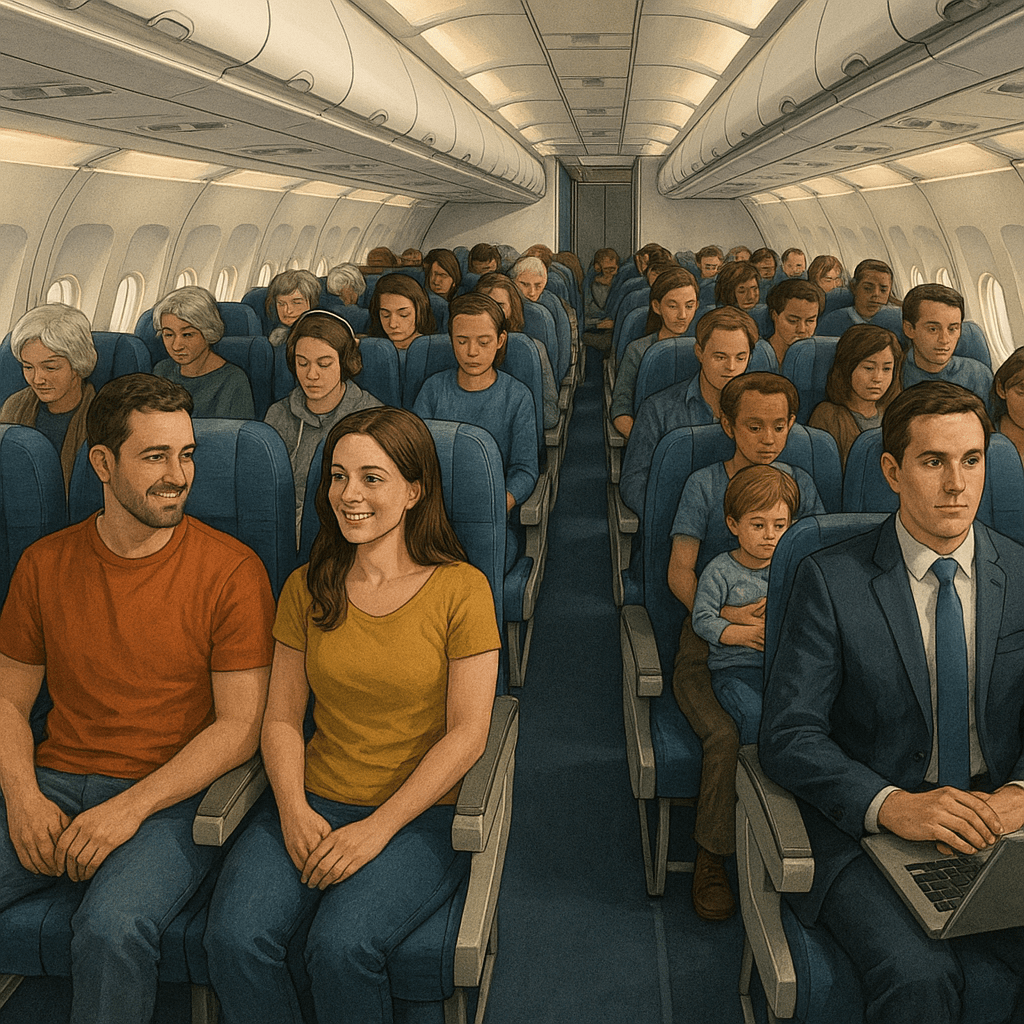

According to a recent article in the Economist, some U.S. airlines have “started charging higher per-person fares for single-passenger bookings than for identical itineraries with two people.” However, the difference in fares held only for round-trip tickets that included a weekday return flight. For round-trip tickets with a return flight on Saturday, the per-ticket price was the same whether booking for two people or for one person. Briefly explain why an airline might expect to increase its profit using this pricing strategy.

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about firms using price discrimination, so you may want to review Chapter 15, Sections 15.5

Step 2: Answer the question by explaining why an airline might expect to increase its profit by charging people traveling alone a higher ticket price than the price it charges per ticket to two people traveling together. The airline is attempting to increase its profit by using price discrimination. Price discrimination involves charging different prices to different customers for the same good or service when the price difference isn’t due to differences in cost. Firms who able to price discriminate increase their profits by doing so.

In Chapter 15, Section 15.5, we call the airlines the “kings of price discrimination” because they often charge many different prices for tickets on the same flight. One key way that airlines practice price discrimination is by charging higher prices to business travelers—who are likely to have a lower price elasticity of demand—than to leisure travelers—who are likely to have a higher price elasticity of demand. To employ this strategy, airlines have to successfully identify which flyers are business travelers. Someone flying alone is more likely than someone flying in a group of two or more people to be a business traveler. In addition, business travelers often attempt to complete their trips before the weekend. Therefore, people returning from a trip on a Saturday or Sunday are more likely to be leisure travelers.

We can conclude that an airline can expect to increase its profit using the pricing strategy discussed in the Economist article because the strategy helps the airline to better identify business travelers.