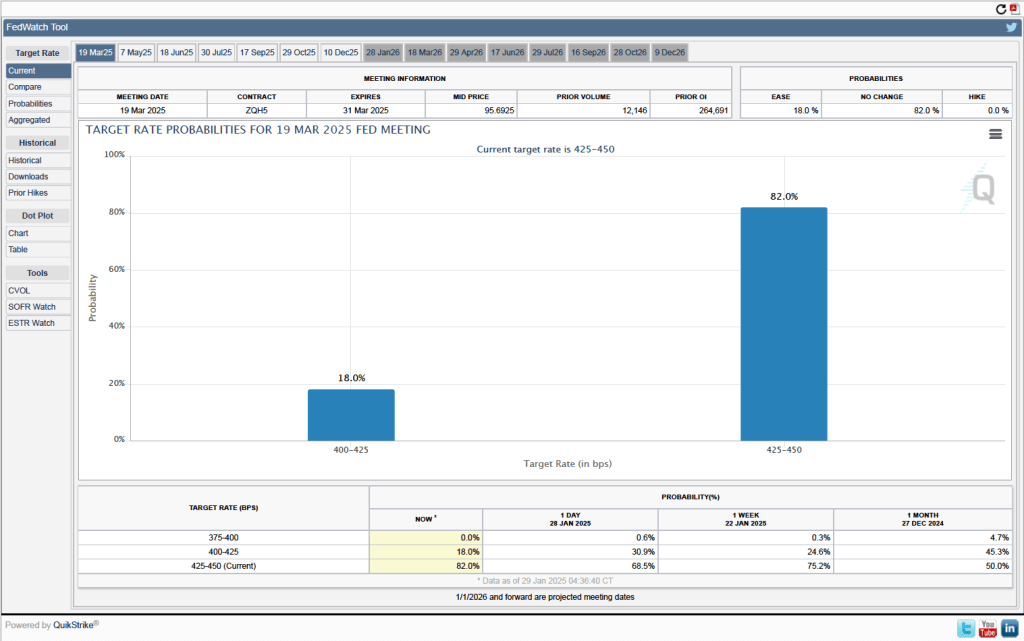

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell at a press conference following a meeting of the FOMC (photo from federalreserve.gov)

Members of the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had signaled that the committee was likely to leave its target range for the federal funds rate unchanged at 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent at its meeting today (January 29), which, in fact, was what they did. As Fed Chair Jerome Powell put it at a press conference following the meeting:

“We see the risks to achieving our employment and inflation goals as being roughly in balance. And we are attentive to the risks on both sides of our mandate. … [W]e do not need to be in a hurry to adjust our policy stance.”

The next scheduled meeting of the FOMC is March 18-19. It seems likely that the committee will also keep its target rate constant at that meeting. Although at his press conference, Powell noted that “We’re not on any preset course.” And that “Policy is well-positioned to deal with the risks and uncertainties that we face in pursuing both sides of our dual mandate.” The statement the committee released after the meeting showed that the decision to leave the target rate unchanged was unanimous.

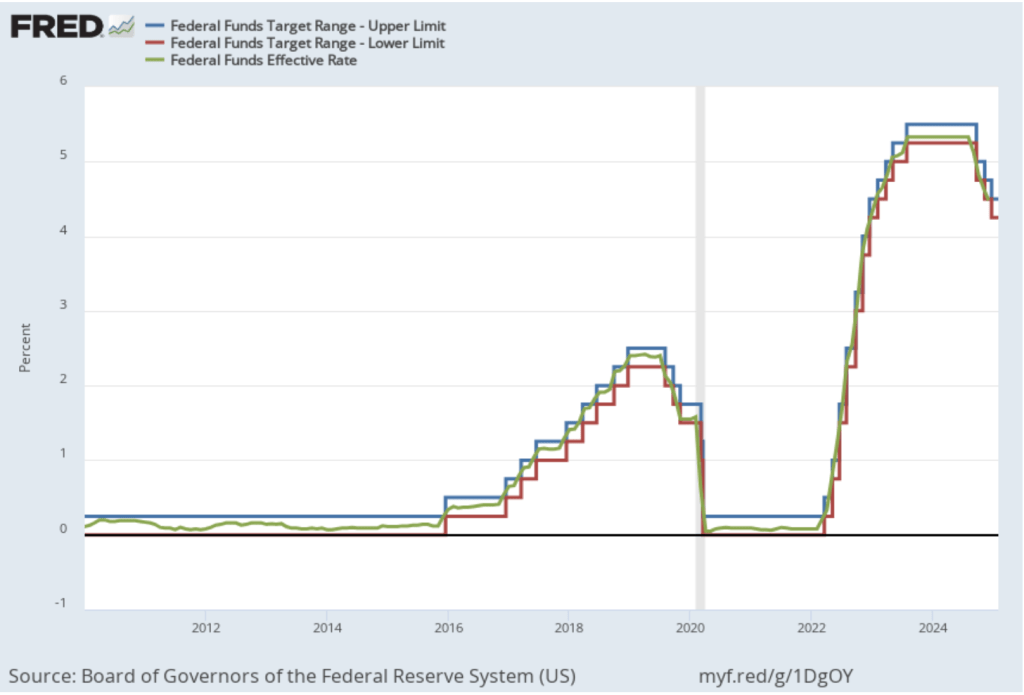

The following figure shows, for the period since January 2010, the upper bound (the blue line) and lower bound (the red line) for the FOMC’s target range for the federal funds rate and the actual values of the federal funds rate (the green line) during that time. Note that the Fed is successful in keeping the value of the federal funds rate in its target range.

A week ago, President Donald Trump in a statement to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland noted his intention to take actions to reduce oil prices. And that “with oil prices going down, I’ll demand that interest rates drop immediately.” As we noted in this recent post about Fed Governor Michael Barr stepping down as Fed Vice Chair for Supervision, there are indications that the Trump administration may attempt to influence Fed monetary policy.

In his press conference, Powell was asked about the president’s statement and responded that he had “No comment whatever on what the president said.” When asked whether the president had spoken to him about the need to lower interest rates, Powell said that he “had no contact” with the president. Powell stated in response to another question that “I’m not going to—I’m not going to react or discuss anything that any elected politician might say ….”

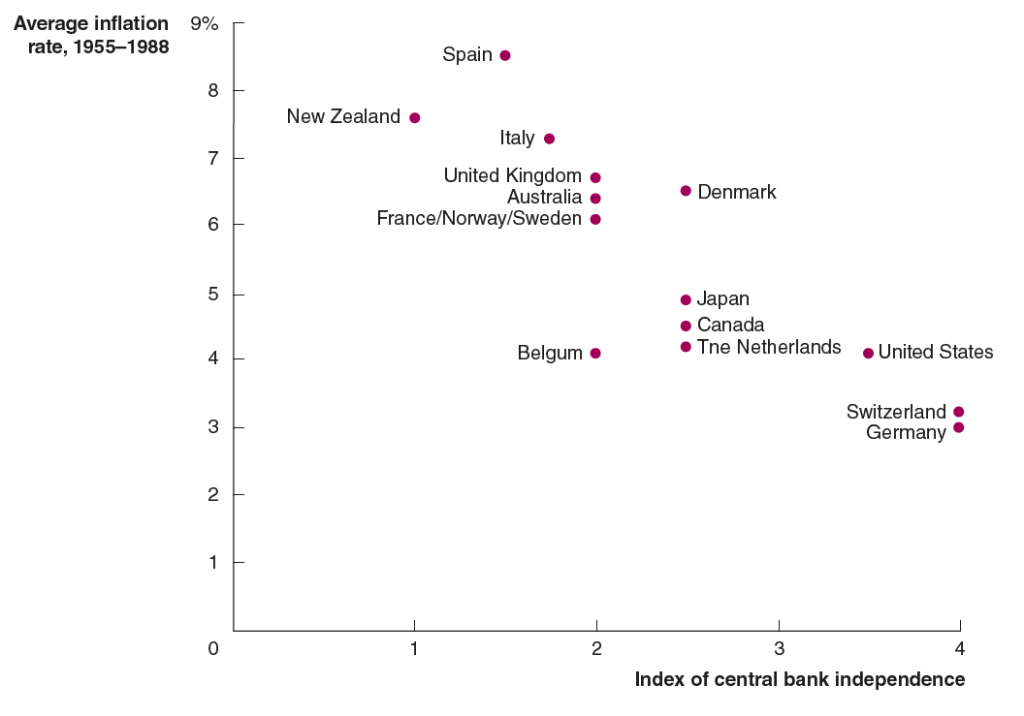

As we noted earlier, it seems likely that the FOMC will leave its target for the federal funds rate unchanged at its meeting on March 18-19. One indication of expectations of future rate cuts comes from investors who buy and sell federal funds futures contracts. (We discuss the futures market for federal funds in this blog post.) As shown in the following figure, today these investors assign a probability of 82.0 percent to the FOMC keeping its target range for the federal funds rate unchanged at the current range of 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent at the March meeting. Investors assign a probability of only 18.0 percent to the committee cutting its target range by 25 basis points at that meeting.