Image generated by GTP-4o of people engaging in economic forecasting

How do we know when we’re in a recession? Most economists and policymakers accept the decisions of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), a private research group located in Cambridge, Massachusetts (see Macroeconomics, Chapter 10, Section 10.3). Typically, the NBER is slow in announcing that a recession has begun because it takes time to gather and analyze economic data. The NBER didn’t announce that a recession had begun in December 2007 until 11 months later in November 2008. When the NBER announced in June 2020 that a recession had begun in February 2020, it was considered to be an unusually fast decision.

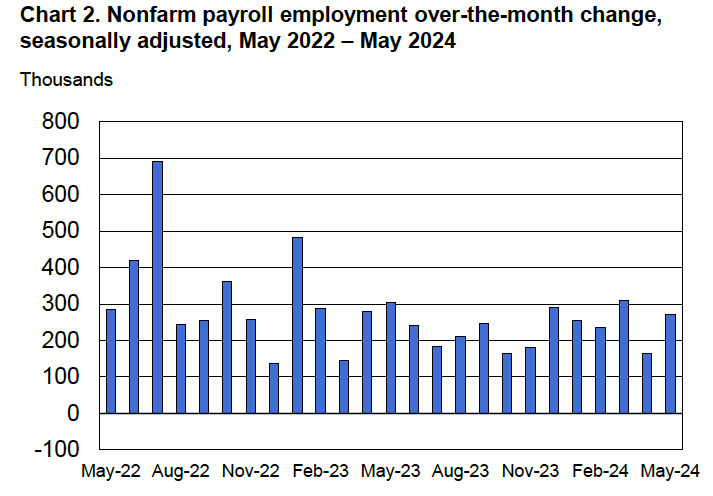

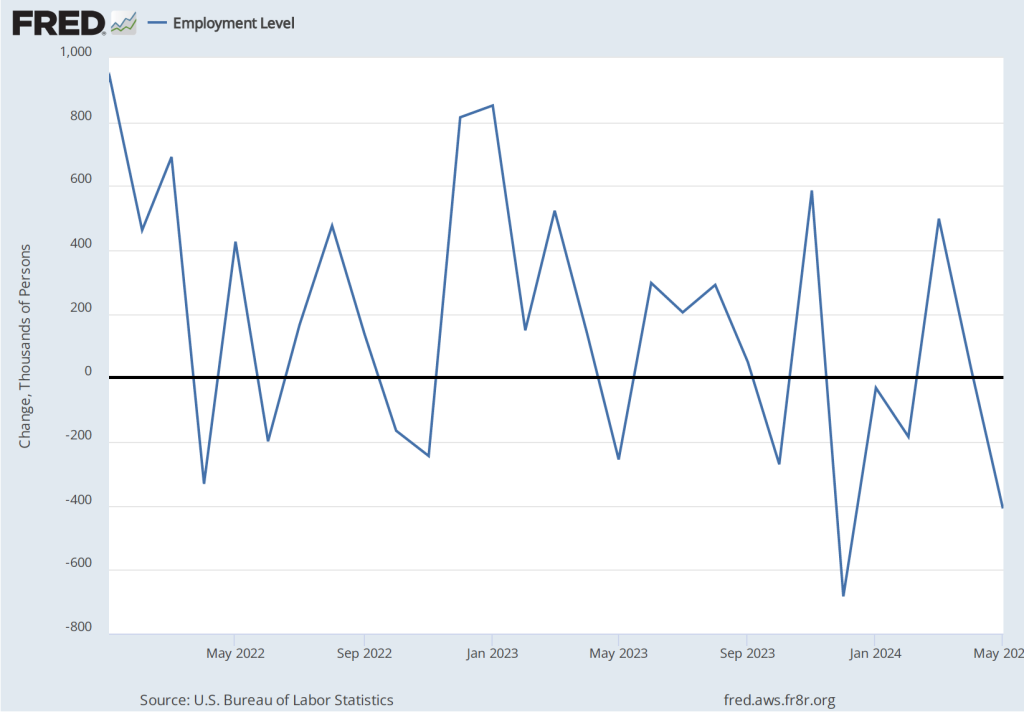

On its website, the NBER notes that: “The NBER’s traditional definition of a recession is that it is a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.” The NBER lists the data it considers when determining whether a recession has begun (or ended), including: “real personal income less transfers (PILT), nonfarm payroll employment, real personal consumption expenditures, manufacturing and trade sales adjusted for price changes, employment as measured by the household survey, and industrial production.” In practice, it is normally the case that an NBER business cycle peak coincides with the peak in nonfarm payroll employment and an NBER business cycle trough coincides with a trough in the same employment series.

Of course, policymakers at the Fed don’t wait until the NBER announces that a recession has begun when formulating monetary policy. Members of the Fed’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) monitor a wide range of data series as the series become available. The broadest measure of the state of the economy is real GDP, which is only available quarterly, and the data are released with a lag. For instance, the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s “advance” (first) estimate of real GDP in the first quarter of 2025 won’t be released until April 30.

Given the importance of GDP, there are several groups that attempt to nowcast GDP. A nowcast is a forecast that incorporates all the information available on a certain date about the components of spending that are included in GDP. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta both release nowcasts of GDP. They use different methodologies, so their forecasts are not identical. Today (March 3), the two estimates are surprisingly far apart. First, here is the nowcast from the NY Fed:

This nowcast indicates that real GDP will grow in the first quarter of 2025 at a 2.94 percent annual rate. That would be an increase from growth of 2.3 percent in the fourth quarter of 2024.

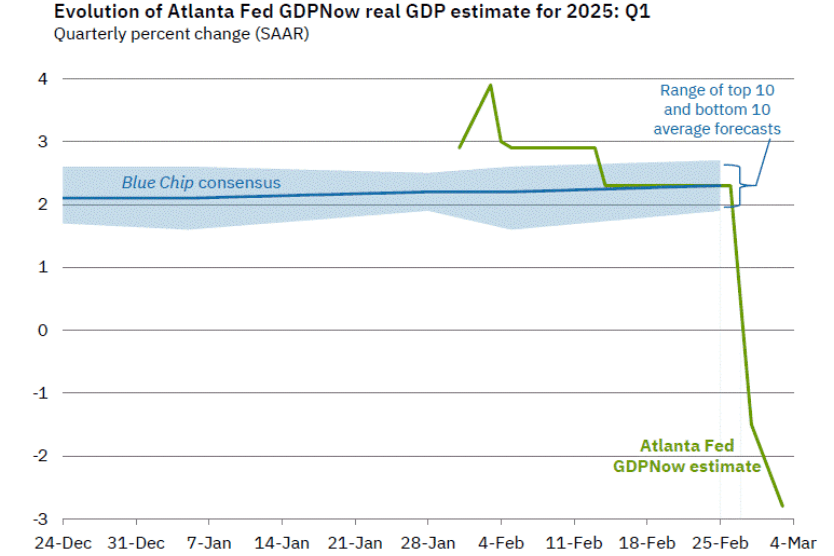

The nowcast from the Atlanta Fed—which they call GDPNow—is strikingly different:

The Atlanta Fed nowcast indicates that real GDP in the first quarter of 2025 will decline by 2.8 percent at an annual rate. If accurate, this forecast indicates that—far from the solid expansion in economic activity that the NY Fed is forecasting—the U.S. economy in the first quarter of 2025 will contract at the fastest rate since the first quarter of 2009, near the end of the severe 2007–2009 downturn (leaving aside the highly unusual declines in the first three quarters of 2020 during the Covid pandemic).

What explains such a large difference between these two forecasts? First, note that the Atlanta Fed includes in its graphic the range of forecasts from Blue Chip Indicators. These forecasts are collected from 50 or more economists who work in the private sector at banks, brokerages, manufacturers, and other firms. The graphic shows that the Blue Chip forecasters do not expect that the economy grew as much as the NY Fed’s nowcast indicates, but the forecasters do expect solid growth rate of 2 percent or more. So, the Atlanta Fed’s forecast appears to be an outlier.

Second, the NY Fed updates its nowcast only once per week, whereas the Atlanta Fed updates its forecast after the release of each data series that enters its model. So, the NY Fed nowcast was last updated on February 28, while the Atlanta Fed nowcast was updated today. Since February 28, the Atlanta Fed has incorporated into its nowcast data on the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing index and data on construction spending from the Census Bureau. Incorporating these data resulted in the Atlanta Fed’s nowcast of first quarter real GDP growth declining from –1.5 percent on February 28 to –2.8 percent on March 3.

But incorporating more data explains only part of the discrepancy between the two forecasts because even as of February 28 the forecasts were far apart. The remaining discrepancy is due to the different methodologies employed by the economists at the two regional Feds in building their nowcasting models.

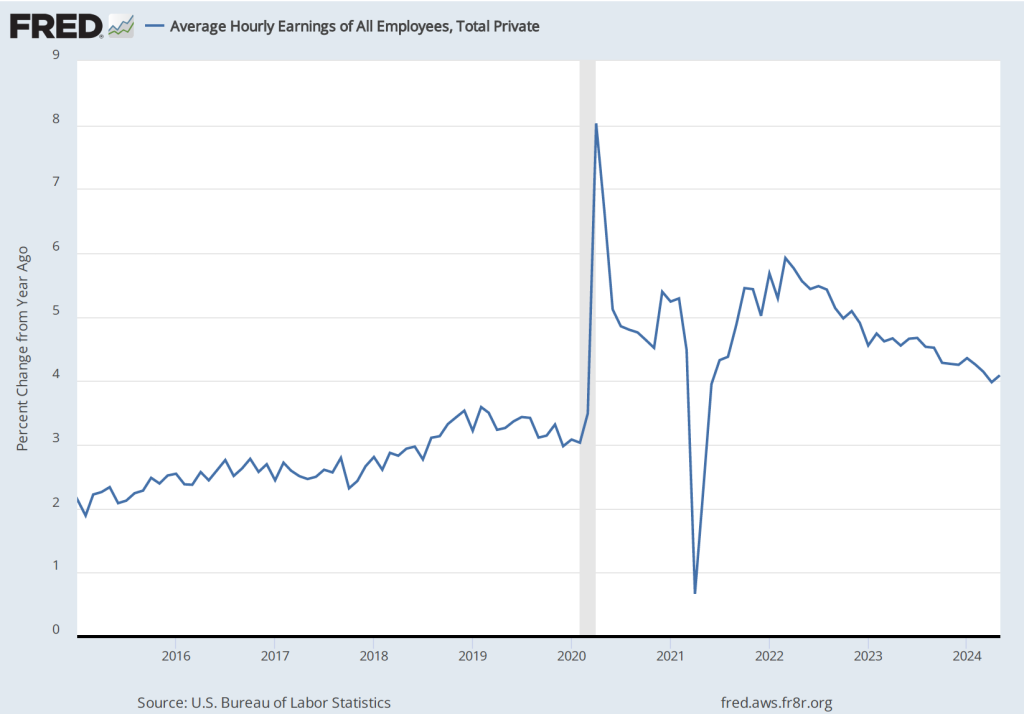

Which forecast is more accurate? We’ll get some indication on Friday (March 7) when the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases its “Employment Situation” report for February. Economists surveyed are expecting that the payroll survey will estimate that there was a net increase of 160,000 jobs in February, up from a net increase of 143,000 jobs in January. If that expectation is accurate, it would seem unlikely that production declined in the first quarter to the extent that the Atlanta Fed nowcast is indicating. But, as we discuss in this blog post from 2022, macro data can be unreliable at the beginning of a recession. If we are currently in a recession, then even an initial estimate of a solid net increase in jobs in February could later be revised sharply downward.