Image generated by GTP-4o

In a post earlier this week, we noted that according to the usually reliable GDPNow forecast from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, real GDP in the first quarter will decline by 2.8 percent. (The forecast was updated yesterday on the basis of additional data releases to a slightly less pessimistic –2.4 percent decline.) This morning (March 7), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its “Employment Situation” report (often called the “jobs report”) for February. The data in the report show no sign that the U.S. economy is in a recession. We should add the caveat, however, that at the beginning of a recession the data in the jobs report can be subject to large revisions.

The jobs report has two estimates of the change in employment during the month: one estimate from the establishment survey, often referred to as the payroll survey, and one from the household survey. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 9.1 (Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.1), many economists and Federal Reserve policymakers believe that employment data from the establishment survey provide a more accurate indicator of the state of the labor market than do either the employment data or the unemployment data from the household survey. (The groups included in the employment estimates from the two surveys are somewhat different, as we discuss in this post.)

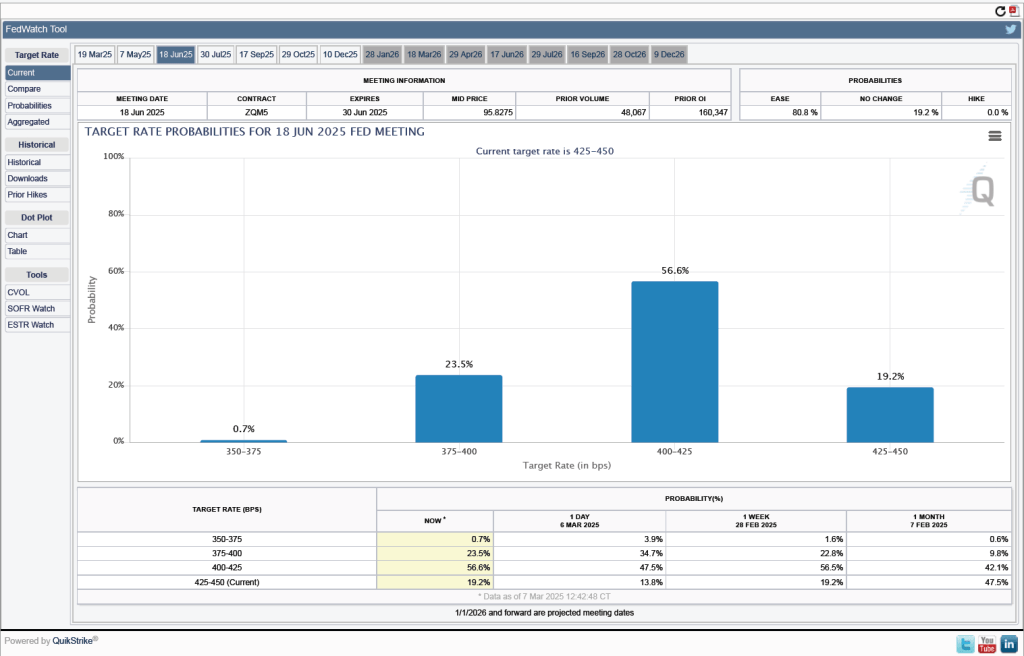

According to the establishment survey, there was a net increase of 151,000 jobs during February. This increase was below the increase of 160,000 that economists had forecast. The previously reported increase for December was revised upward, while the previously reported increase for January was revised downward. The net change in jobs, taking the revisions for those two months together, was 2,000 lower than originally estimated. (The BLS notes that: “Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.”) The following figure from the jobs report shows the net change in payroll employment for each month in the last two years.

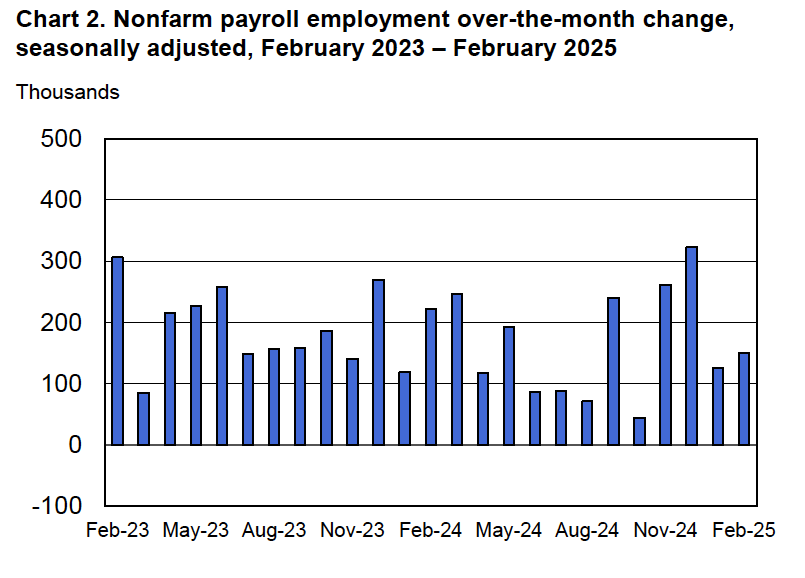

The unemployment rate rose slightly to 4.1 percent in February from 4.0 percent in January. As the following figure shows, the unemployment rate has been remarkably stable in recent months, staying between 4.0 percent and 4.2 percent in each month since May 2024. Last December, the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) forecast that the unemployment rate for 2025 would average 4.3 percent.

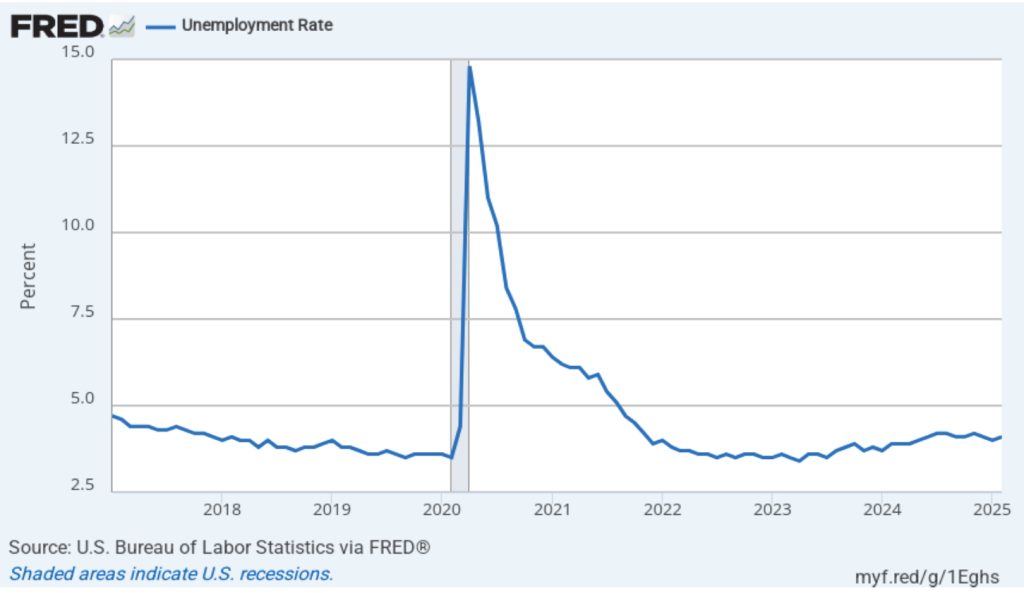

As the following figure shows, the net change in jobs from the household survey moves much more erratically than does the net change in jobs from the establishment survey. The net change in jobs as measured by the household survey for February showed a sharp decrease of 588,000 jobs following a very large increase of 2,234,000 jobs in January. In any particular month, the story told by the two surveys can be inconsistent with employment increasing in one survey while falling in the other. The difference was particularly dramatic this month. (In this blog post, we discuss the differences between the employment estimates in the two surveys.)

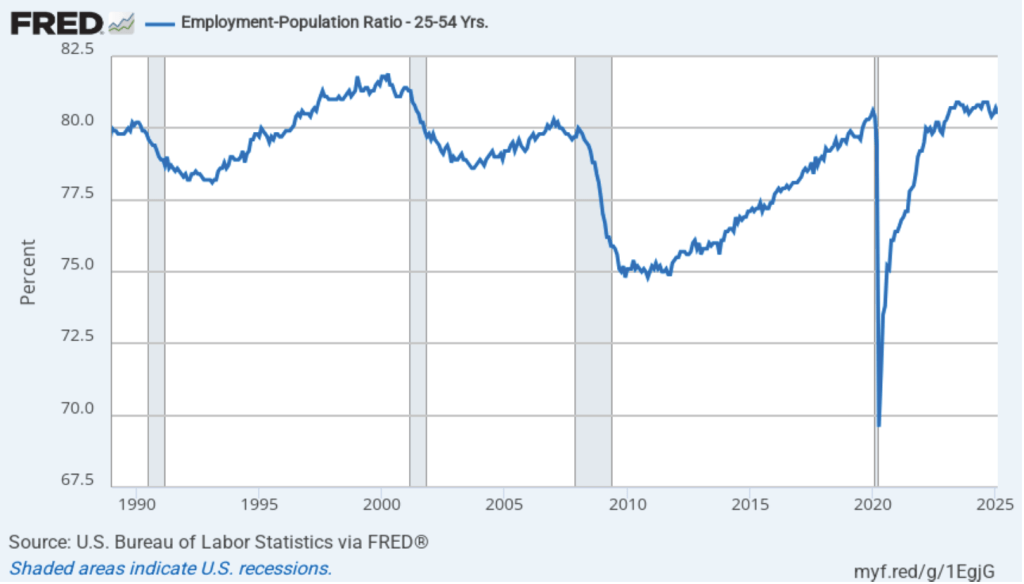

Another concerning sign in the household survey is the fall in the employment-population ratio for prime age workers—those aged 25 to 54. The ratio declined from 80.7 percent in January to 80.5 percent in February. Although the employment-population is still high relative to the average level since 2001, it’s now well below the high of 80.9 percent in mid-2024. Continuing declines in this ratio would indicate a significant softening in the labor market.

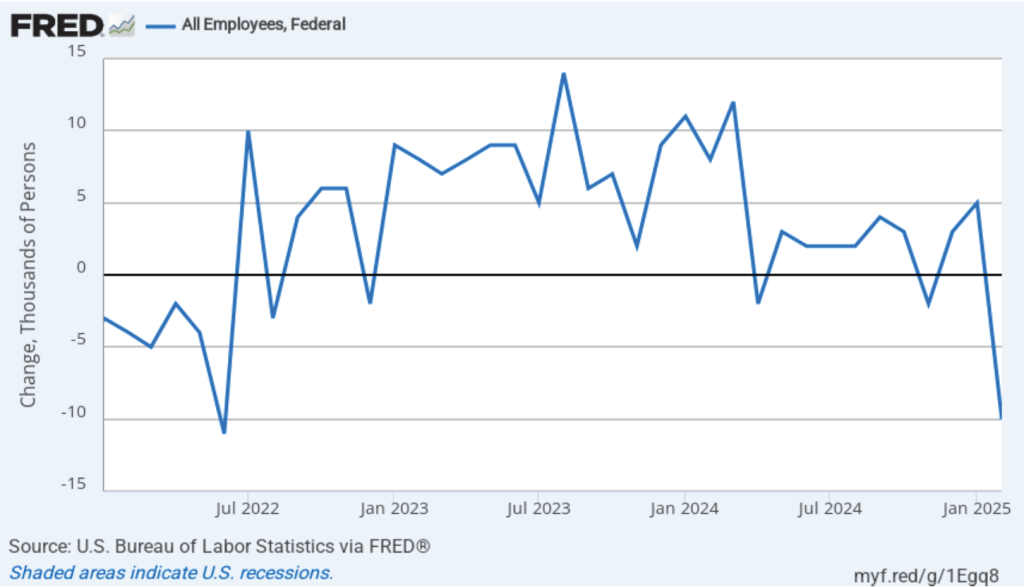

It’s unclear how many federal workers have been laid off since the Trump Administration took office. The household survey shows a decline in total federal government employment of 10,000 in February. The household survey was conducted in the week that included February 12, so, it’s possible that next month’s jobs report may find a more significant decline.

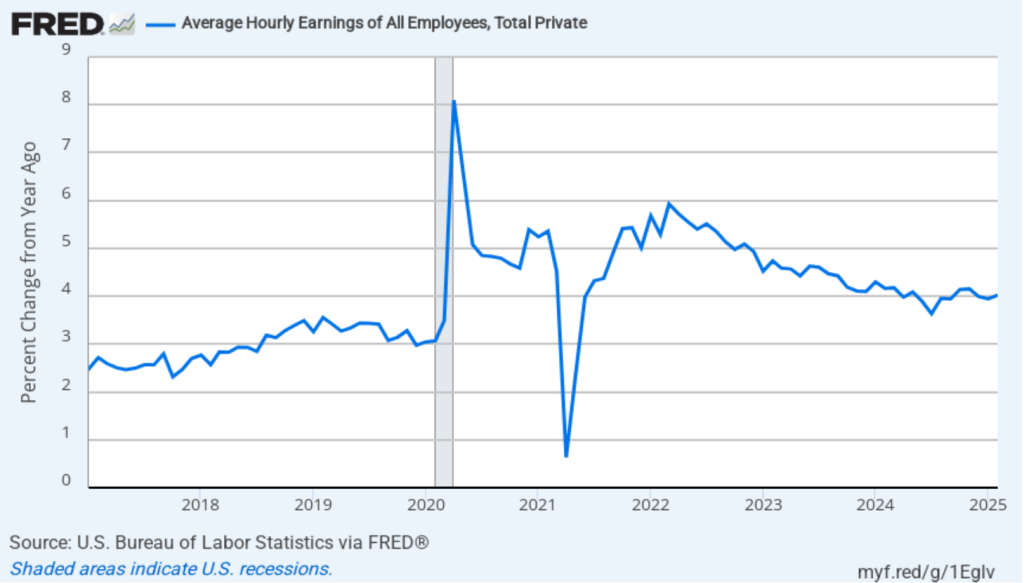

The establishment survey also includes data on average hourly earnings (AHE). As we noted in this post, many economists and policymakers believe the employment cost index (ECI) is a better measure of wage pressures in the economy than is the AHE. The AHE does have the important advantage of being available monthly, whereas the ECI is only available quarterly. The following figure shows the percentage change in the AHE from the same month in the previous year. The AHE increased 4.0 percent in February, up slightly from 3.9 percent in January.

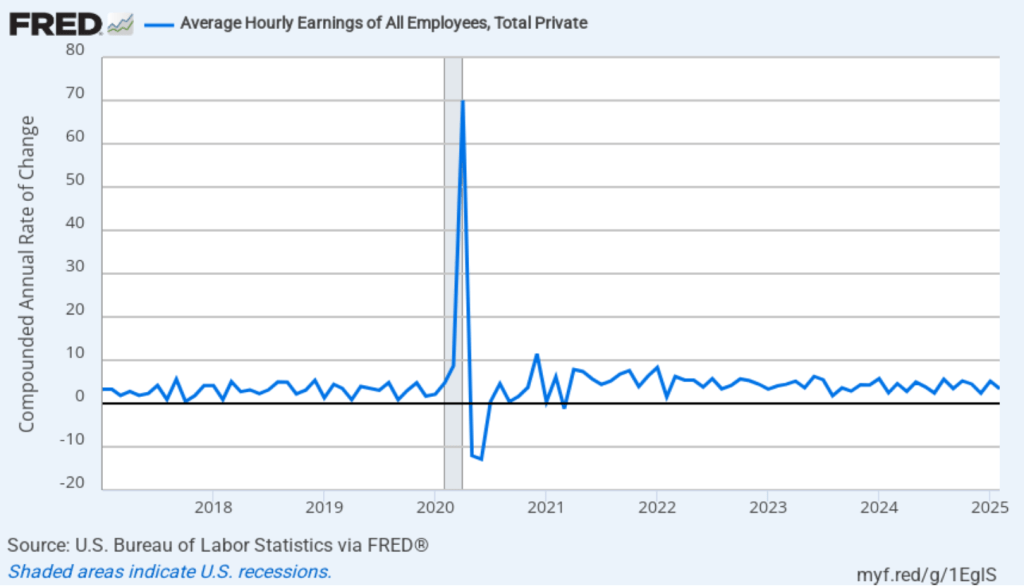

The following figure shows wage inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month wage inflation, whereas this figure shows 1-month wage inflation.) One-month wage inflation is much more volatile than 12-month wage inflation—note the very large swings in 1-month wage inflation in April and May 2020 during the business closures caused by the Covid pandemic. The February 1-month rate of wage inflation was 3.4 percent, a decline from the surprisingly high 5.2 percent rate in December. Whether measured as a 12-month increase or as a 1-month increase, AHE is still increasing somewhat more rapidly than is consistent with the Fed achieving its 2 percent target rate of price inflation.

Today’s jobs report leaves the situation facing the Federal Reserve’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) largely unchanged. There are some indications that the economy may be weakening, as shown by some of the data in the jobs report and by some of the data incorporated by the Atlanta Fed in its pessimistic nowcast of first quarter real GDP. But the Fed hasn’t yet brought inflation down to its 2 percent annual target. In addition, it’s unclear how the Trump Administration’s policies—particularly with respect to tariff increases—might affect the economy. Speaking today at an event at the University of Chicago, Fed Chair Jerome Powell observed the following:

“Looking ahead, the new Administration is in the process of implementing significant policy changes in four distinct areas: trade, immigration, fiscal policy, and regulation. It is the net effect of these policy changes that will matter for the economy and for the path of monetary policy. While there have been recent developments in some of these areas, especially trade policy, uncertainty around the changes and their likely effects remains high. As we parse the incoming information, we are focused on separating the signal from the noise as the outlook evolves. We do not need to be in a hurry, and are well positioned to wait for greater clarity.”

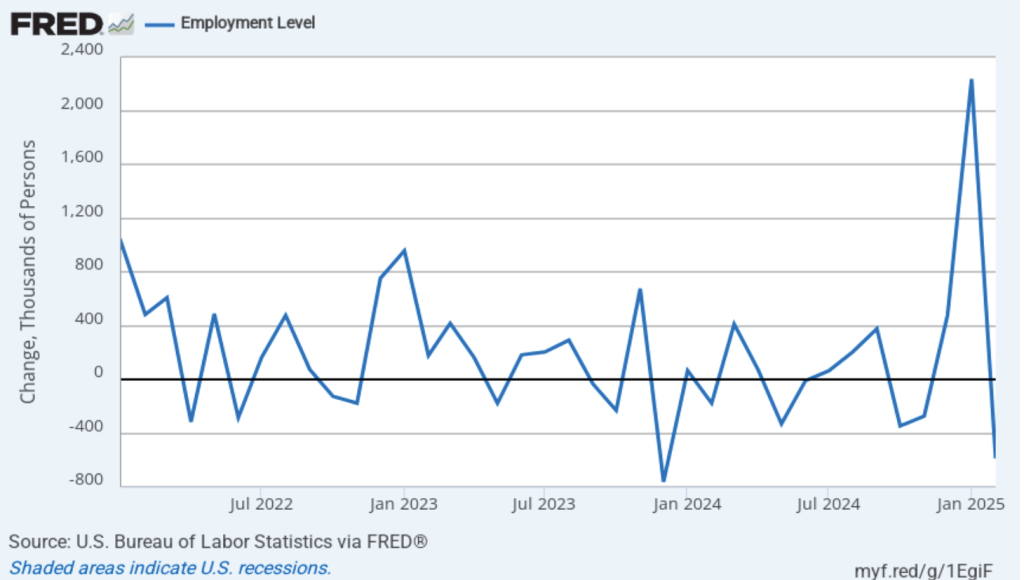

The likeliest outcome is that the FOMC will keep its target for the federal funds rate unchanged, perhaps for several meetings, unless additional data are released that clearly show the economy to be weakening.

One indication of expectations of future cuts in the target for the federal funds rate comes from investors who buy and sell federal funds futures contracts. (We discuss the futures market for federal funds in this blog post.) The data from the futures market indicates that investors don’t expect that the FOMC will cut its target for the federal funds rate at either its March 18–19 or May 6–7 meetings. As shown in the following figure, only at the FOMC’s June 17–18 meeting do investors assign a greater than 50 percent probability to the committee cutting its target. As of this afternoon, investors assign a probability of only 19.2 percent to the FOMC keeping its target unchanged at 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent at that meeting. They assign a probability of 80.8 percent to the committee cutting its target rate by at least 0.25 percentage point (25 basis points) at that meeting.