Photo of Michael Barr from federalreserve.gov

President-elect Donald Trump has stated that he believes that presidents should have more say in monetary policy. There had been some speculation that once in office Trump would try to replace Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, although Trump later indicated that he would not attempt to replace Powell until Powell’s term as chair ends in May 2026. Can the president remove the Fed Chair or another member of the Board of Governors? The relevant section of the Federal Reserve Act States that: “each member [of the Board of Governors] shall hold office for a term of fourteen years from the expiration of the term of his predecessor, unless sooner removed for cause by the President.”

“Removed for cause” has generally been interpreted by lawyers inside and outside of the Fed as not authorizing the president to remove a member of the Board of Governors because of a disagreement over monetary policy. The following flat statement appears on a page of the web site of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: “Federal Reserve officials cannot be fired simply because the president or a member of Congress disagrees with Federal Reserve decisions about interest rates.”

At his press conference following the November 7 meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), Powell was asked by a reporter: “do you believe the President has the power to fire or demote you, and has the Fed determined the legality of a President demoting at will any of the other Governors with leadership positions?” Powell replied: “Not permitted under the law.” Despite Powell’s definitive statement, because no president has attempted to remove a member of the Board of Governors, the federal courts have never been asked to decide what the “removed for cause” language in the Federal Reserve Act means.

The president is free to remove the members of most agencies of the federal government, so why shouldn’t he or she be able to remove the Fed Chair? When Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913, it intended the central bank to be able set policy independently of the president and Congress. The president and members of Congress may take a short-term view of policy, focusing on conditions at the time that they run for reelection. Expansionary monetary policies can temporarily boost employment and output in the short run, but cause inflation to increase in the long run.

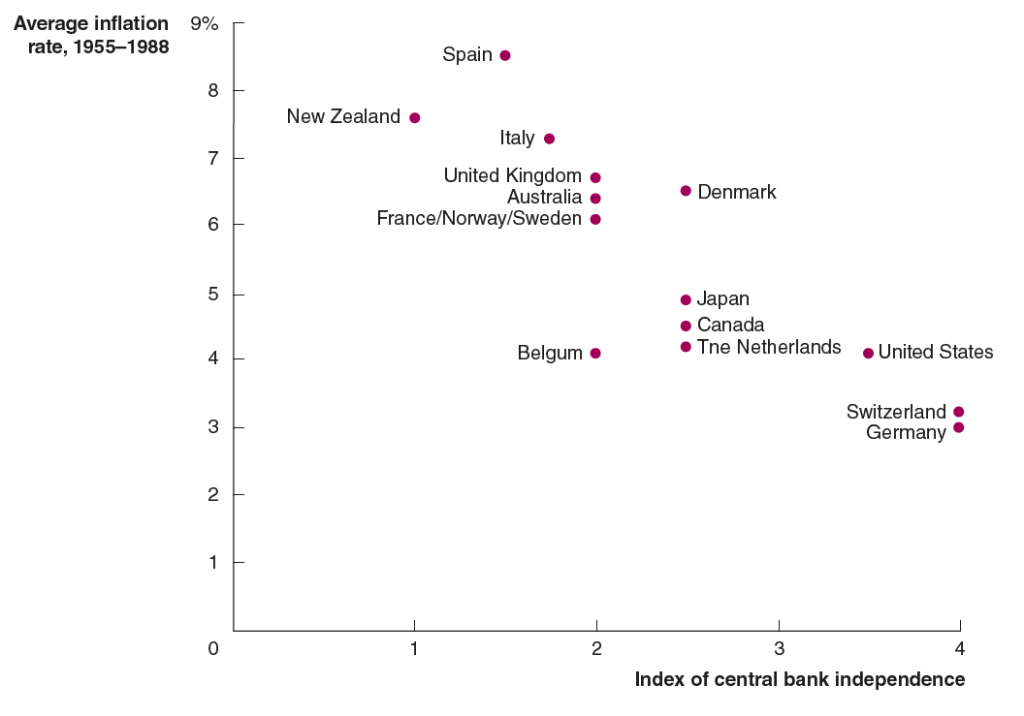

As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 17, Section 17.4 (Economics, Chapter 27, Section 27.4), in a classic study, Alberto Alesina and Lawrence Summers compared the degree of central bank independence and the inflation rate for 16 high-income countries during the years from 1955 to 1988. As the following figure shows, countries with highly independent central banks, such as the United States, Switzerland, and Germany, had lower inflation rates than countries whose central banks had little independence, such as New Zealand, Italy, and Spain.

Yesterday, something unusual happened that might seem to undermine Fed independence. Michael Barr, a member of the Board of Governors and the Board’s Vice Chair for Supervision, said that on February 28 he will step down from his position as Vice Chair, but will remain on the Board. His term as Vice Chair was scheduled to end in July 2026. His term on the Board is scheduled to end in January 2032.

Barr has been an advocate for stricter regulation of banks, including higher capital requirements for large banks. These positions have come in for criticism from banks, from some policymakers, and from advisers to Trump. Barr stated that he was stepping down because: “The risk of a dispute over the position could be a distraction from our mission. In the current environment, I’ve determined that I would be more effective in serving the American people from my role as governor.” Trump will nominate someone to assume the position of vice chair, but because there are no openings on the Board of Governors he will have to choose from among the current members.

Does this episode indicate that Fed independence is eroding? Not necessarily because the Fed’s regulatory role is distinct from its monetary policy role. As financial journalist Neil Irwin points out, “top [Fed] bank supervision officials view their role as more explicitly carrying out the regulatory agenda of the president who appointed them—and that a new president is entitled, in reasonable time, to their own choices.” In the past, other members of the Board who have held positions similar to the one Barr holds have resigned following the election of a new president.

So, it’s unclear at this point whether Barr’s resignation as vice chair indicates that the incoming Trump Administration will be taking steps to influence the Fed’s monetary policy actions or how the Fed’s leadership will react if it does.