Nvidia’s headquarters in Santa Clara, California. (Photo from nvidia.com)

Nvidia was founded in 1993 by Jensen Huang, Chris Malachowsky, and Curtis Priem, electrical engineers who started the company with the goal of designing computer chips that would increase the realism of images in video games. The firm achieved a key breakthrough in 1999 when it invented the graphics processing unit, or GPU, which it marketed under the name GeForce256. In 2001, Microsoft used a Nvidia chip in its new Xbox video game console, helping Nvidia to become the dominant firm in the market for GPUs.

The technology behind GPUs has turned out to be usable not just for gaming, but also for powering AI—artificial intelligence—software. The market for Nvidia’s chips exploded witth technology giants Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon, as well as many startups ordering large quantites of Nvidia’s chips.

By 2016, Nvidia CEO Jen-Hsun Huang could state in an interview that: “At no time in the history of our company have we been at the center of such large markets. This can be attributed to the fact that we do one thing incredibly well—it’s called GPU computing.” Earlier this year, an article in the Economist noted that: “Access to GPUs, and in particular those made by Nvidia, the leading supplier, is vital for any company that wants to be taken seriously in artificial intelligence (AI).”

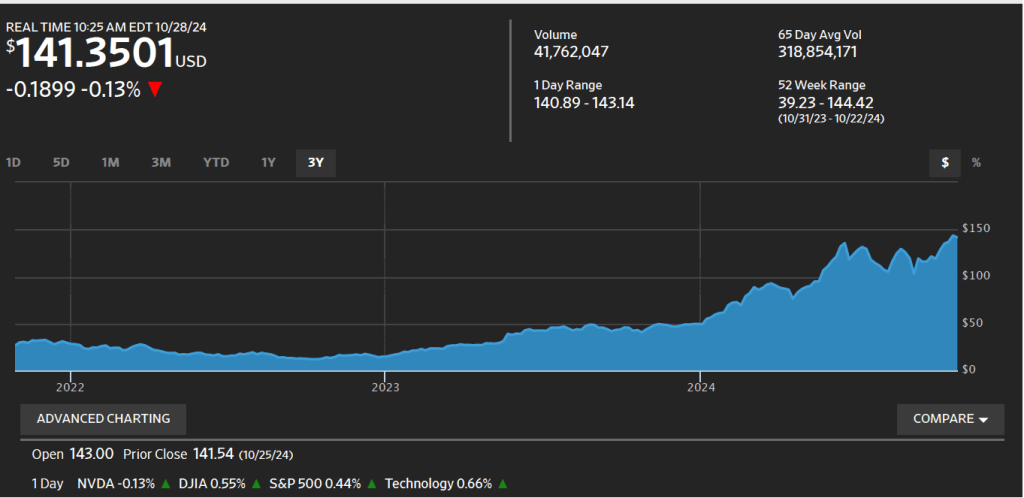

Nvidia’s success has been reflected in its stock price. When Nvidia became a public company in 1999 by undertaking an initial public offering (IPO) of stock, a share of the firm’s stock had a price of $0.04, adjusted for later stock splits. The large profits Nvidia has been earning in recent years have caused its stock price to rise to more than $140 dollars a share.

(With a stock split, a firm reduces the price per share of its stock by giving shareholders additional shares while holding the total value of the shares constant. For example, in June of this year Nvidia carried out a 10 for 1 stock split, which gave shareholders nine shares of stock for each share they owned. The total value of the shares was the same, but each share now had a price that was 10 percent of its price before the split. We discuss the stock market in Microeconomics, Chapter 8, Section 8.2, Macroeconomics, Chapter 6, Section 6.2, and Economics, Chapter 8, Section 8.2.)

The following figure from the Wall Street Journal shows the sharp increase in Nvidia’s stock price over the past three years as AI has become an increasingly important part of the economy.

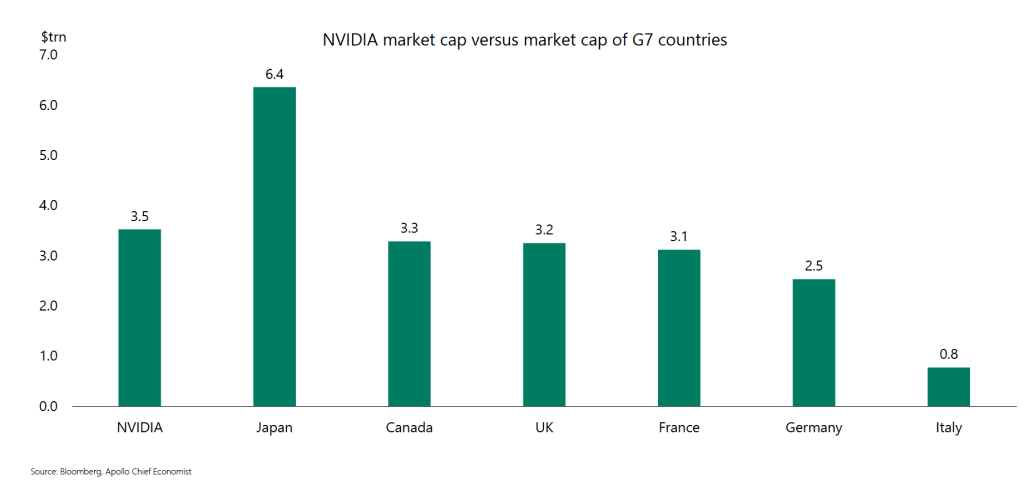

Nvidia’s market capitalization (or market cap)—the total value of all of its outstanding shares of stock—is $3.5 trillion. How large is that? Torsten Sløk, the chief economist at Apollo, an asset management firm, has noted that, as shown in the following figure, Nvidia’s market cap is larger than the total market caps—the total value of all the publicly traded firms—in five large economies.

Can Nvidia’s great success continue? Will it be able to indefinitely dominate the market for AI chips? As we noted in Apply the Concept “Do Large Firms Live Forever?” in Microeconomics Chapter 14, in the long run, even the most successful firms eventually have their positions undermined by competition. That Nvidia has a larger stock market value than the total value of all the public companies in Germany or the United Kingdom is extraordinary and seems impossible to sustain. It may indicate that investors have bid up the price of Nvidia’s stock above the value that can be justified by a reasonable forecast of its future profits.

There are already some significant threats to Nvidia’s dominant position in the market for AI chips. GPUs were originally designed to improve computer displays of graphics rather than to power AI software. So, one way of competing with Nvidia that some startups are trying to exploit is to design chips specifically for use in AI. It’s also possible that larger chips may make it possible to use fewer chips than when using GPUs, possibly reducing the total cost of the chips necessary to run sophisticated AI software. In addition, existing large technology firms, such as Amazon and Microsoft, have been developing chips that may be able to compete with Nvidia.

As with any firm, Nvidia’s continued success requires it to innovate sufficiently to stay ahead of the many competitors that would like to cut into the firm’s colossal profits.