Image generated by ChatGPT 5

“Artificial intelligence is profoundly limiting some young Americans’ employment prospects, new research shows.” That’s the opening sentence of a recent opinion column in the Wall Street Journal. The columnist was reacting to a new academic paper by economists Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen of Stanford University. (See also this Substack post by Chandar that summarizes the results of their paper.) The authors find that:

“[S]ince the widespread adoption of generative AI, early-career workers (ages 22-25) in the most AI-exposed occupations have experienced a 13 percent relative decline in employment … In contrast, employment for workers in less exposed fields and more experienced workers in the same occupations has remained stable or continued to grow. Furthermore, employment declines are concentrated in occupations where AI is more likely to automate, rather than augment, human labor.”

The authors conclude that “our results are consistent with the hypothesis that generative AI has begun to significantly affect entry-level employment.”

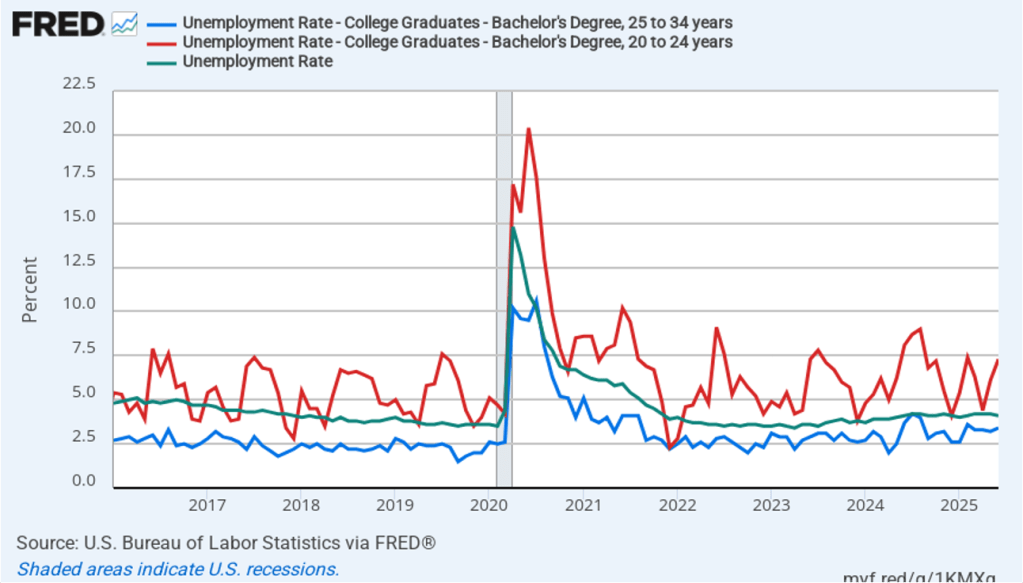

About a month ago, we wrote a blog post looking at whether unemployment among young college graduates has been abnormally high in recent months. The following figure from that post shows that over time, the unemployment rates for the youngest college graduates (the red line) is nearly always above the unemployment rate for the population as a whole (the green line), while the unemployment rate for college graduates 25 to 34 years old (the blue line) is nearly always below the unemployment rate for the population as a whole. In July of this year, the unemployment rate for the population as a whole was 4.2 percent, while the unemployment for college graduates 20 to 24 years old was 8.5 percent, and the unemployment rate for college graduates 25 to 34 years old was 3.8 percent.

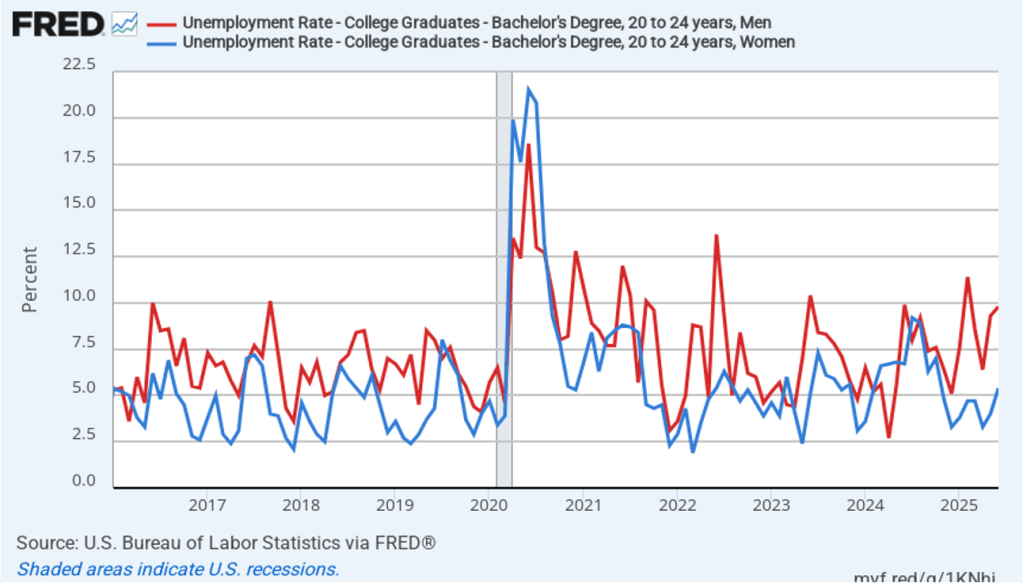

As the following figure (also reproduced from that blog post) shows, the increase in unemployment among young college graduates has been concentrated among males. Does higher male unemployment indicate that AI is eliminating jobs, such as software coding, that are disproportionately male? Data journalist John Burn-Murdoch argues against this conclusion, noting that data shows that “early-career coding employment is now tracking ahead of the [U.S.] economy.”

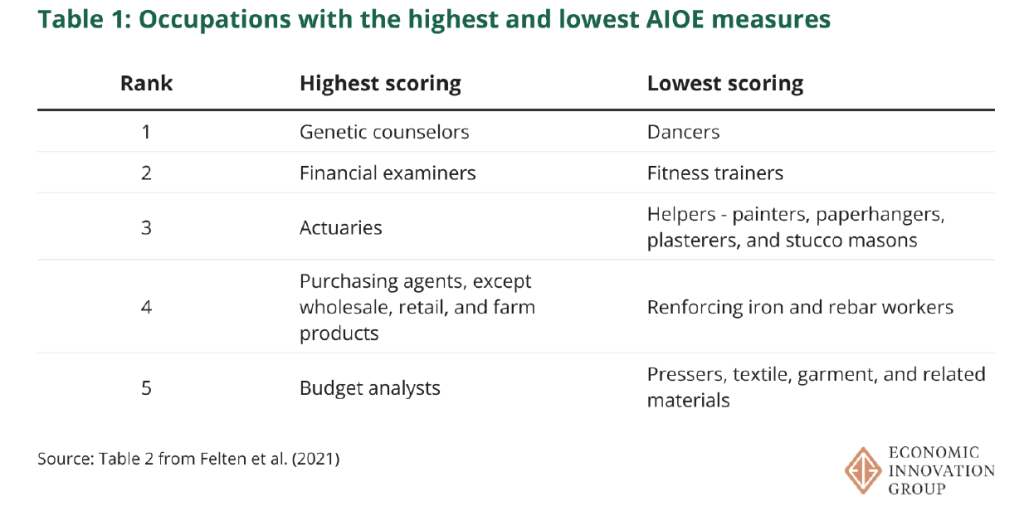

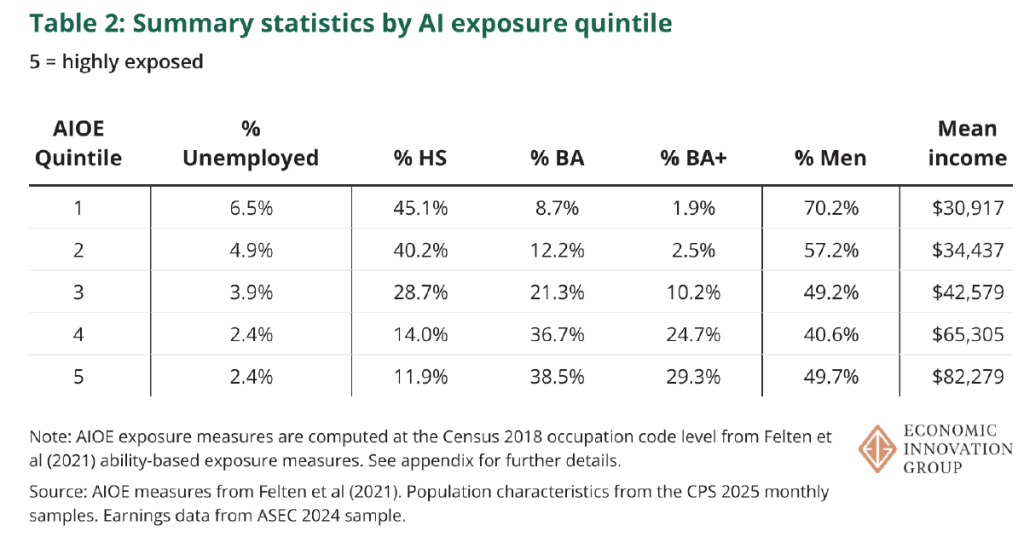

Another recent paper written by Sarah Eckhardt and Nathan Goldschlag of the Economic Innovation Group is also skeptical of the view that firms adopting generative AI programs is reducing employment in certain types of jobs. They use a measure developed by Edward Felton on Princeton University, and Manav Raj and Robert Seamans of New York University of how exposed particular jobs are to AI (AI Occupational Exposure (AIOE)). The following table from Eckhardt and Goldschlag’s paper shows the five most AI exposed jobs and the five least AI exposed jobs.

They divide all occupations into quintiles based on the exposure of the occupations to AI. Their key results are given in the following table, which shows that the occupations that are most exposed to the effects of AI—quintiles 4 and 5—have lower unemployment rates and higher wages than do the occupations that are least exposed to AI.

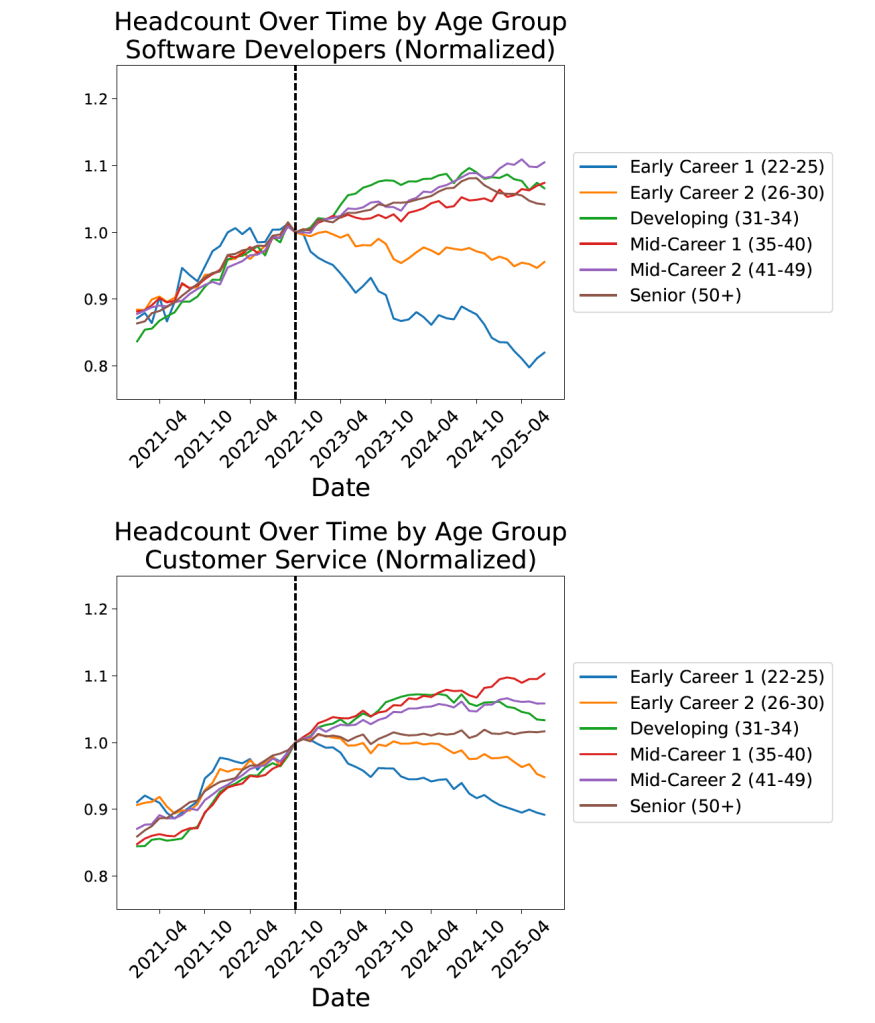

The Brynjolfsson, Chandar, and Chen paper mentioned at the beginning of this post uses a larger data set of workers by occupation from ADP, a private firm that processes payroll data for about 25 percent of U.S. workers. Figure 1 from their paper, reproduced here, shows that employment of workers in two occupations—software developers and customer service—representative of those occupations most exposted to AI declined sharply after generative AI programs became widely available in late 2022.

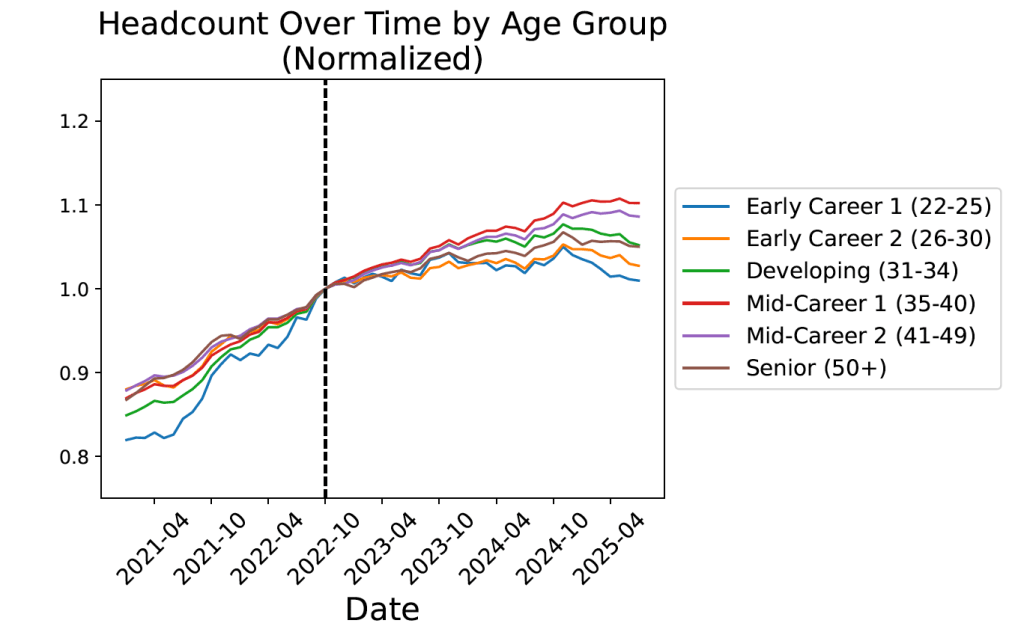

They don’t find this pattern for all occupations, as shown in the following figure from their paper.

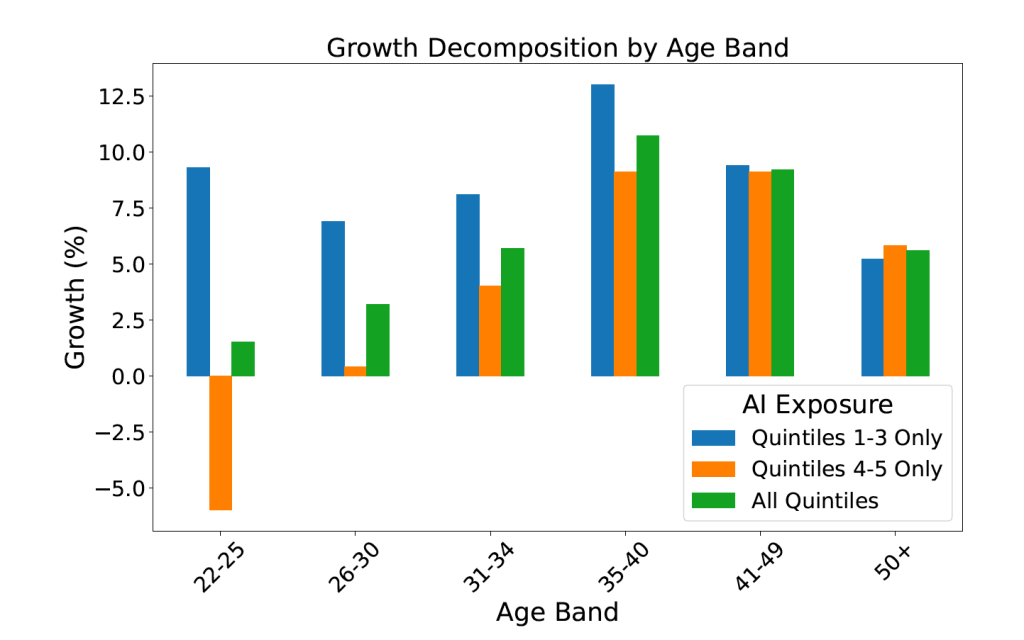

Finally, they show results by occupational quintiles, with workers ages aged 22 to 25 being hard hit in the two occupational quintiles (4 and 5) most exposted to AI. The data show total employment growth from October 2022 to July 2025 by age group and exposure to AI.

Economics blogger Noah Smith has raised an interesting issue about Brynjolfsson, Chandar, and Chen’s results. Why would we expect that the negative effect of AI on employment to be so highly concentrated among younger workers? Why would employment in the most AI exposed occupations be growing rapidly among workers aged 35 and above? Smith wonders “why companies would be rushing to hire new 40-year-old workers in those AI-exposed occupations.” He continues:

“Think about it. Suppose you’re a manager at a software company, and you realize that the coming of AI coding tools means that you don’t need as many software engineers. Yes, you would probably decide to hire fewer 22-year-old engineers. But would you run out and hire a ton of new 40-year-old engineers?“

Both the papers discussed here are worth reading for their insights on how the labor market is evolving in the generative AI era. But taken together, they indicate that it is probably too early to arrive at firm conclusions about the effects of generative AI on the job market for young college graduates or other groups.