Image generated by ChatGPT 5 of a 1981 IBM personal computer.

The modern era of information technology began in the 1980s with the spread of personal computers. A key development was the introduction of the IBM personal computer in 1981. The Apple II, designed by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak and introduced in 1977, was the first widely used personal computer, but the IBM personal computer had several advantages over the Apple II. For decades, IBM had been the dominant firm in information technology worldwide. The IBM System/360, introduced in 1964, was by far the most successful mainframe computer in the world. Many large U.S. firms depended on IBM to meet their needs for processing payroll, general accounting services, managing inventories, and billing.

Because these firms were often reliant on IBM for installing, maintaining, and servicing their computers, they were reluctant to shift to performing key tasks with personal computers like the Apple II. This reluctance was reinforced by the fact that few managers were familiar with Apple or other early personal computer firms like Commodore or Tandy, which sold the TRS-80 through Radio Shack stores. In addition, many firms lacked the technical staffs to install, maintain, and repair personal computers. Initially, it was easier for firms to rely on IBM to perform these tasks, just as they had long been performing the same tasks for firms’ mainframe computers.

By 1983, the IBM PC had overtaken the Apple II as the best-selling personal computer in the United States. In addition, IBM had decided to rely on other firms to supply its computer chips (Intel) and operating system (Microsoft) rather than develop its own proprietary computer chips and operating system. This so-called open architecture made it possible for other firms, such as Dell and Gateway, to produce personal computers that were similar to IBM’s. The result was to give an incentive for firms to produce software that would run on both the IBM PC and the “clones” produced by other firms, rather than produce software for Apple personal computers. Key software such as the spreadsheet program Lotus 1-2-3 and word processing programs, such as WordPerfect, cemented the dominance of the IBM PC and the IBM clones over Apple, which was largely shut out of the market for business computers.

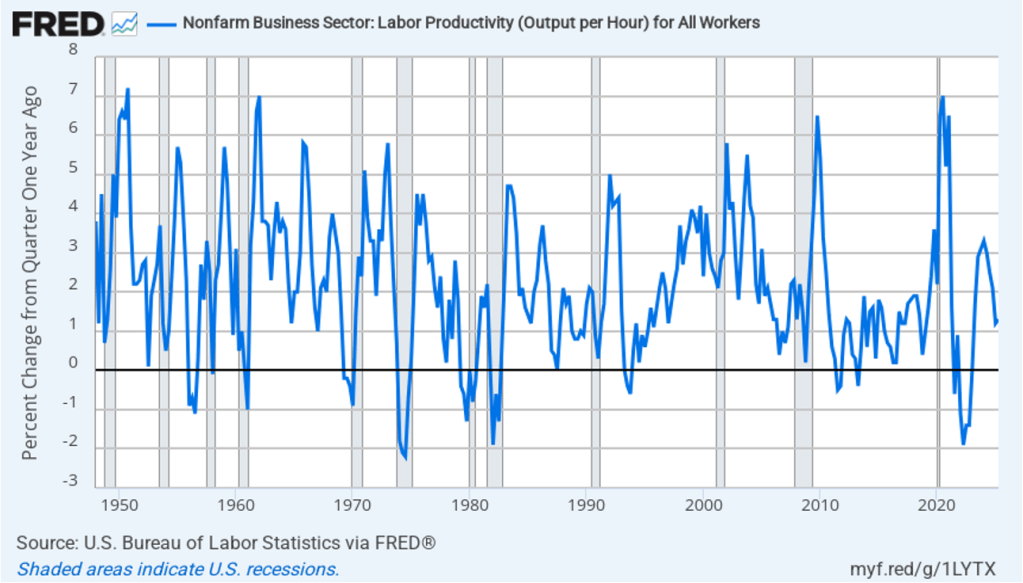

As personal computers began to be widely used in business, there was a general expectation among economists and policymakers that business productivity would increase. Productivity, measured as output per hour of work, had grown at a fairly rapid average annual rate of 2.8 percent between 1948 and 1972. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 10 (Economics, Chapter 20 and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 14) rising productivity is the key to an economy achieving a rising standard of living. Unless output per hour worked increases over time, consumption per person will stagnate. An annual growth rate of 2.8 percent will lead to noticeable increases in the standard of living.

Economists and policymakers were concerned when productivity growth slowed beginning in 1973. From 1973 to 198o, productivity grew at an annual rate of only 1.3 percent—less than half the growth rate from 1948 to 1972. Despite the widespread adoption of personal computers by businesses, during the 1980s, the growth rate of productivity increased only to 1.5 percent. In 1987, Nobel laureate Robert Solow of MIT famously remarked: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Economists labeled Solow’s observation the “productivity paradox.” With hindsight, it’s now clear that it takes time for businesses to adapt to a new technology, such as personal computers. In addition, the development of the internet, increases in the computing power of personal computers, and the introduction of innovative software were necessary before a significant increase in productivity growth rates occurred in the mid-1990s.

Result when ChatGPT 5 is asked to create an image illustrating ChatGPT

The release of ChatGPT in November 2022 is likely to be seen in the future as at least as important an event in the evolution of information technology as the introduction of the IBM PC in August 1981. Just as with personal computers, many people have been predicting that generative AI programs will have a substantial effect on the labor market and on productivity.

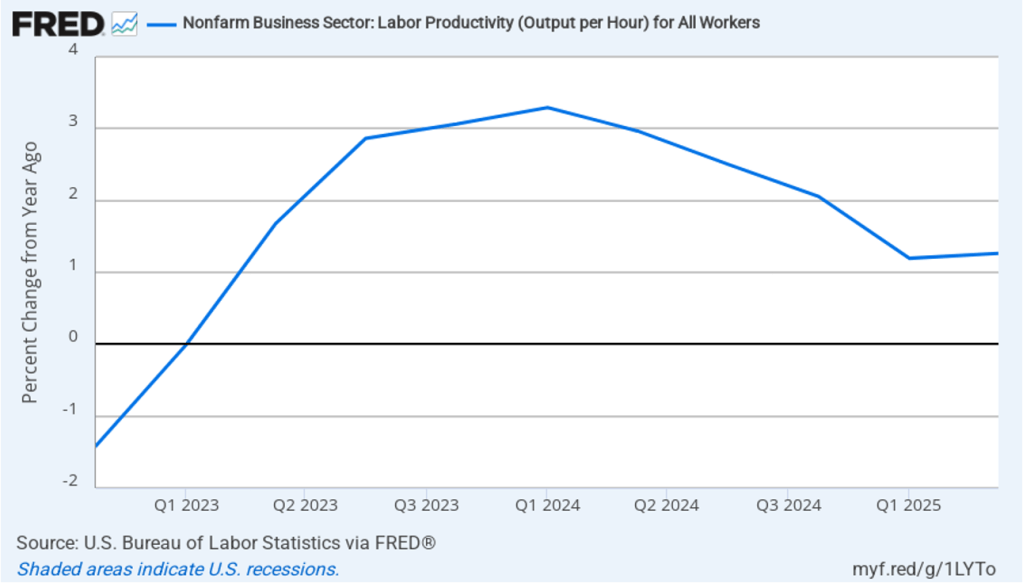

In this recent blog post, we discussed the conflicting evidence as to whether generative AI has been eliminating jobs in some occupations, such as software coding. Has AI had an effect on productivity growth? The following figure shows the rate of productivity growth in each quarter since the fourth quarter of 2022. The figure shows an acceleration in productivity growth beginning in the fourth quarter of 2023. From the fourth quarter of 2023 through the fourth quarter of 2024, productivity grew at an annual rate of 3.1 percent—higher than during the period from 1948 to 1972. Some commentators attributed this surge in productivity to the effects of AI.

However, the increase in productivity growth wasn’t sustained, with the growth rate in the first half of 2025 being only 1.3 percent. That slowdown makes it more likely that the surge in productivity growth was attributable to the recovery from the 2020 Covid recession or was simply an example of the wide fluctuations that can occur in productivity growth. The following figure, showing the entire period since 1948, illustrates how volatile quarterly rates of productivity growth are.

How large an effect will AI ultimately have on the labor market? If many current jobs are replaced by AI is it likely that the unemployment rate will soar? That’s a prediction that has often been made in the media. For instance, Dario Amodei, the CEO of generative AI firm Anthropic, predicted during an interview on CNN that AI will wipe out half of all entry level jobs in the U.S. and cause the unemployment rate to rise to between 10% and 20%.

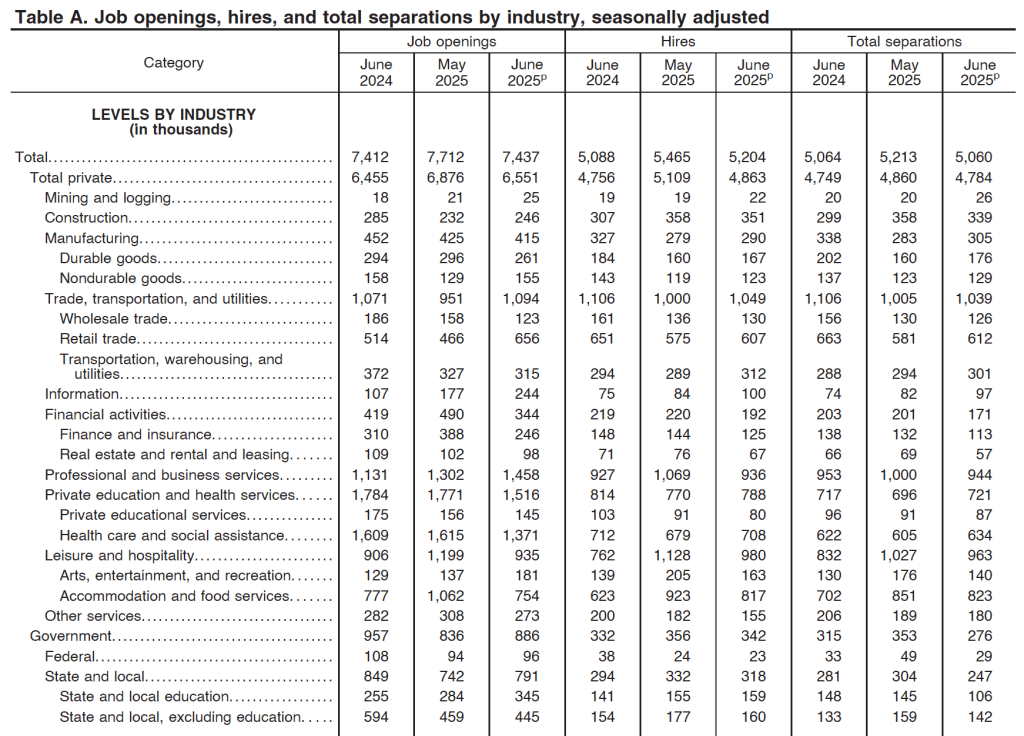

Although Amodei is likely correct that AI will wipe out many existing jobs, it’s unlikely that the result will be a large increase in the unemployment rate. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9 (Economics, Chapter 19 and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 13) the U.S. economy creates and destroys millions of jobs every year. Consider, for instance, the following table from the most recent “Job Openings and Labor Turnover” (JOLTS) report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In June 2025, 5.2 million people were hired and 5.1 million left (were “separated” from) their jobs as a result of quitting, being laid off, or being fired.

Most economists believe that one of the strengths of the U.S. economy is the flexibility of the U.S. labor market. With a few exceptions, “employment at will” holds in every state, which means that a business can lay off or fire a worker without having to provide a cause. Unionization rates are also lower in the United States than in many other countries. U.S. workers have less job security than in many other countries, but—crucially—U.S. firms are more willing to hire workers because they can more easily lay them off or fire them if they need to. (We discuss the greater flexibility of U.S. labor markets in Macroeconomics, Chapter 11 (Economics, Chapter 21).)

The flexibility of the U.S. labor market means that it has shrugged off many waves of technological change. AI will have a substantial effect on the economy and on the mix of jobs available. But will the effect be greater than that of electrification in the late nineteenth century or the effect of the automobile in the early twentieth century or the effect of the internet and personal computing in the 1980s and 1990s? The introduction of automobiles wiped out jobs in the horse-drawn vehicle industry, just as the internet has wiped out jobs in brick-and-mortar retailing. People unemployed by technology find other jobs; sometimes the jobs are better than the ones they had and sometimes the jobs are worse. But economic historians have shown that technological change has never caused a spike in the U.S. unemployment rate. It seems likely—but not certain!—that the same will be true of the effects of the AI revolution.

Which jobs will AI destroy and which new jobs will it create? Except in a rough sense, the truth is that it is very difficult to tell. Attempts to forecast technological change have a dismal history. To take one of many examples, in 1998, Paul Krugman, later to win the Nobel Prize, cast doubt on the importance of the internet: “By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.” Krugman, Amodei and other prognosticators of the effects of technological change simply lack the knowledge to make an informed prediction because the required knowledge is spread across millions of people.

That knowledge only becomes available over time. The actions of consumers and firms interacting in markets mobilize information that is initially known only partially to any one person. In 1945, Friedrich Hayek made this argument in “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” which is one of the most influential economics articles ever written. One of Hayek’s examples is an unexpected decrease in the supply of tin. How will this development affect the economy? We find out only by observing how people adapt to a rising price of tin: “The marvel is that … without an order being issued, without more than perhaps a handful of people knowing the cause, tens of thousands of people whose identity could not be ascertained by months of investigation are made [by the increase in the price of tin] to use the material or its products more sparingly.” People adjust to changing conditions in ways that we lack sufficient information to reliably forecast. (We discuss Hayek’s view of how the market system mobilizes the knowledge of workers, consumers, and firms in Microeconomics, Chapter 2.)

It’s up to millions of engineers, workers, and managers across the economy, often through trial and error, to discover how AI can best reduce the cost of producing goods and services or improve their quality. Competition among firms drives them to make the best use of AI. In the end, AI may result in more people or fewer people being employed in any particular occupation. At this point, there is no way to know.