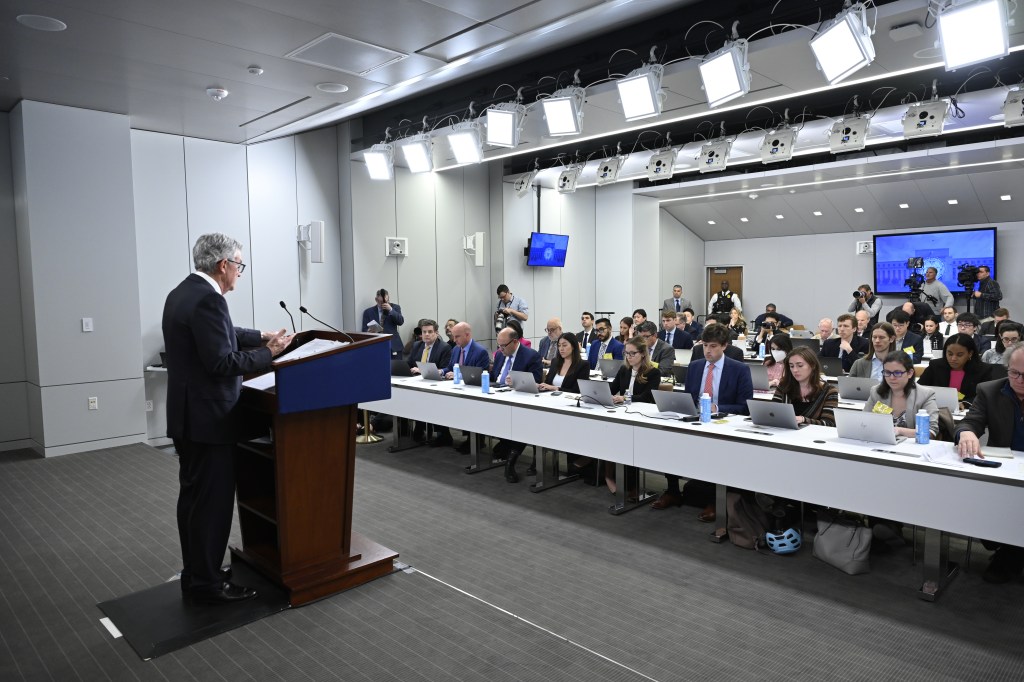

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell at a press conference following a meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (Photo from federal reserve.gov)

Inflation in 2024 is a tale of two quarters. During the first quarter of 2024, inflation ran higher than expected considering the falling inflation rates at the end of 2023. As a result, although at the beginning of the year many economists and Wall Street analysts had expected the Federal Reserve’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) would cut its target for the federal funds rate at least once in the first half of 2024, the FOMC left its target unchanged.

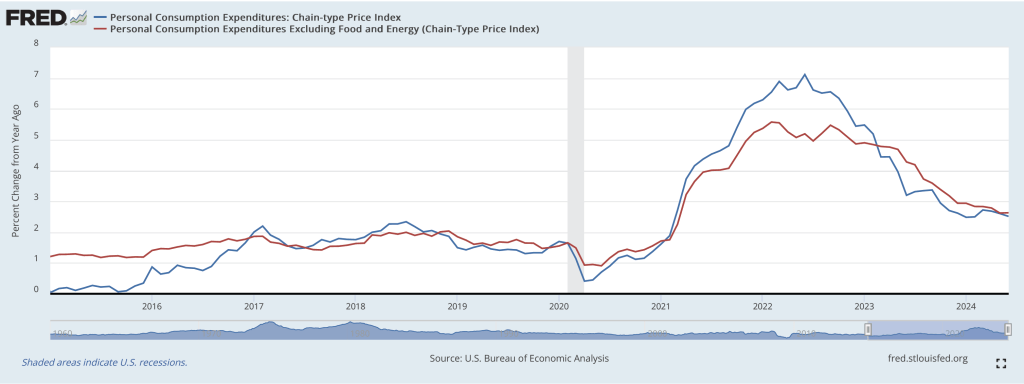

On July 26, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released its “Personal Income and Outlays” report for June. The report includes monthly data on the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. The Fed relies on annual changes in the PCE price index to evaluate whether it’s meeting its 2 percent annual inflation target. The report confirmed that PCE inflation slowed in the second quarter, bringing it closer to the Fed’s 2 percent target.

The following figure shows PCE inflation (blue line) and core PCE inflation (red line)—which excludes energy and food prices—for the period since January 2015 with inflation measured as the percentage change in the PCE from the same month in the previous year. Measured this way, in June PCE inflation (the blue line) was 2.5 percent, down slightly from PCE inflation of 2.6 percent in May. Core PCE inflation (the red line) in June was also 2.5 percent, which was unchanged from May.

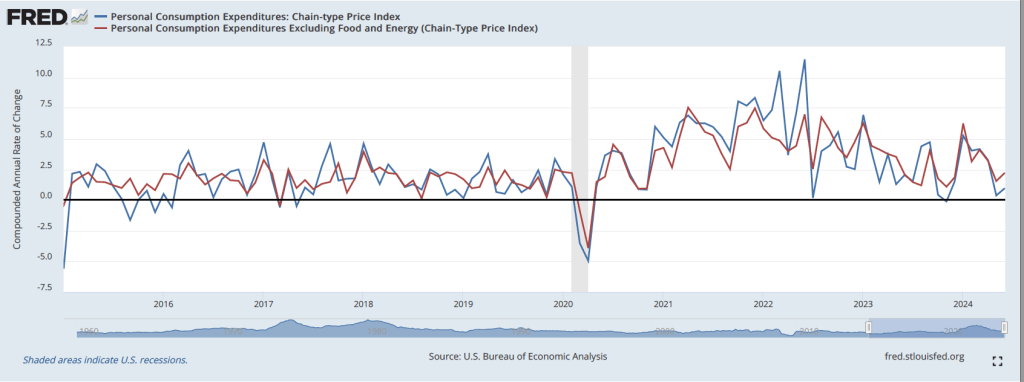

The following figure shows PCE inflation and core PCE inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month inflation, while this figure shows 1-month inflation.) Measured this way, PCE inflation rose in June to 0.9 percent from 0.4 percent in May—although higher in June, inflation was well below the Fed’s 2 percent target in both months. Core PCE inflation rose from 1.5 percent in May to 2.0 percent in June. These data indicate that inflation has been at or below the Fed’s target for the last two months.

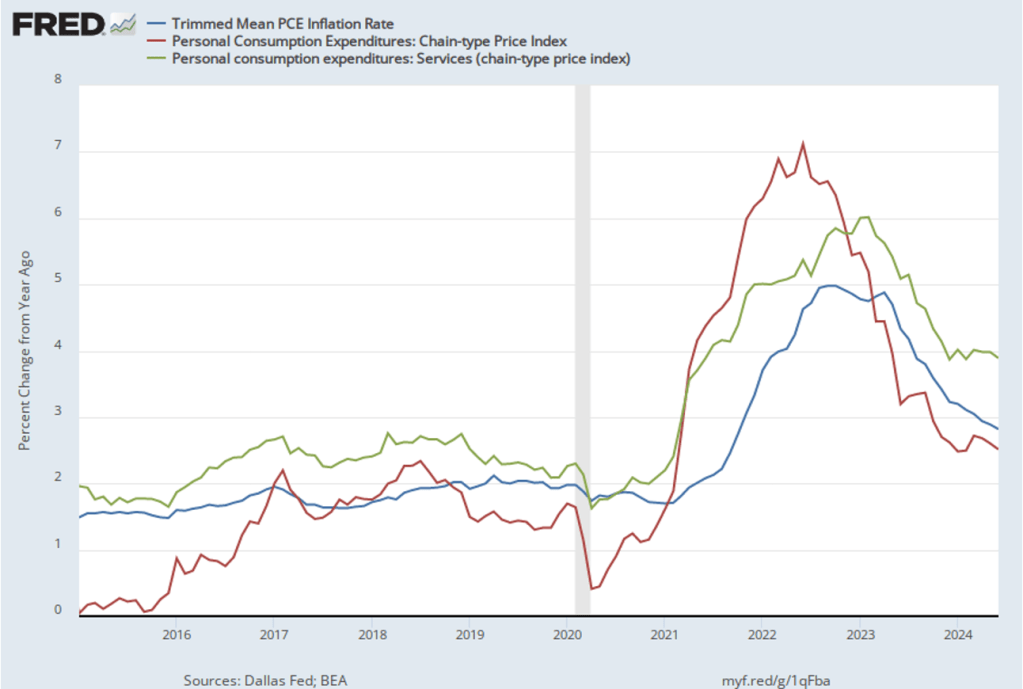

The following figure shows another way of gauging inflation by including the 12-month inflation rate in the PCE (the same as shown in the figure above—although note that PCE inflation is now the red line rather than the blue line), inflation as measured using only the prices of the services included in the PCE (the green line), and the trimmed mean rate of PCE inflation (the blue line). Fed Chair Jerome Powell and other members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) have said that they are concerned by the persistence of elevated rates of inflation in services. The trimmed mean measure is compiled by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas by dropping from the PCE the goods and services that have the highest and lowest rates of inflation. It can be thought of as another way of looking at core inflation by excluding the prices of goods and services that had particularly high or particularly low rates of inflation during the month.

Inflation using the trimmed mean measure was 2.8 percent in June (calculated as a 12-month inflation rate), down only slightly from 2.9 percent in May—and still above the Fed’s target inflation rate of 2 percent. Inflation in services remained high in June at 3.9 percent, down only slightly from 4.0 percent in May.

This month’s PCE inflation data indicate that the inflation rate is still declining towards the Fed’s target, with the low 1-month inflation rates being particularly encouraging. It now seems likely that the FOMC will soon lower the committee’s target for the federal funds rate, which is currently 5.25 percent to 5.50 percent. Remarks by Fed Chair Powell have been interpreted as hinting as much. The next meeting of the FOMC is July 30-31. What do financial markets think the FOMC will decide at that meeting?

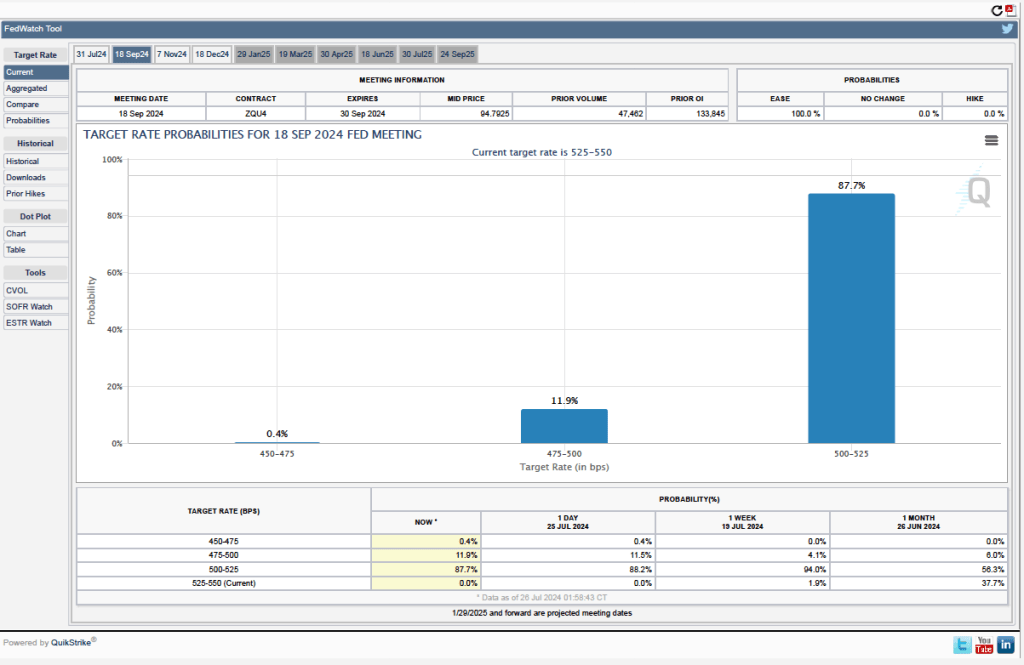

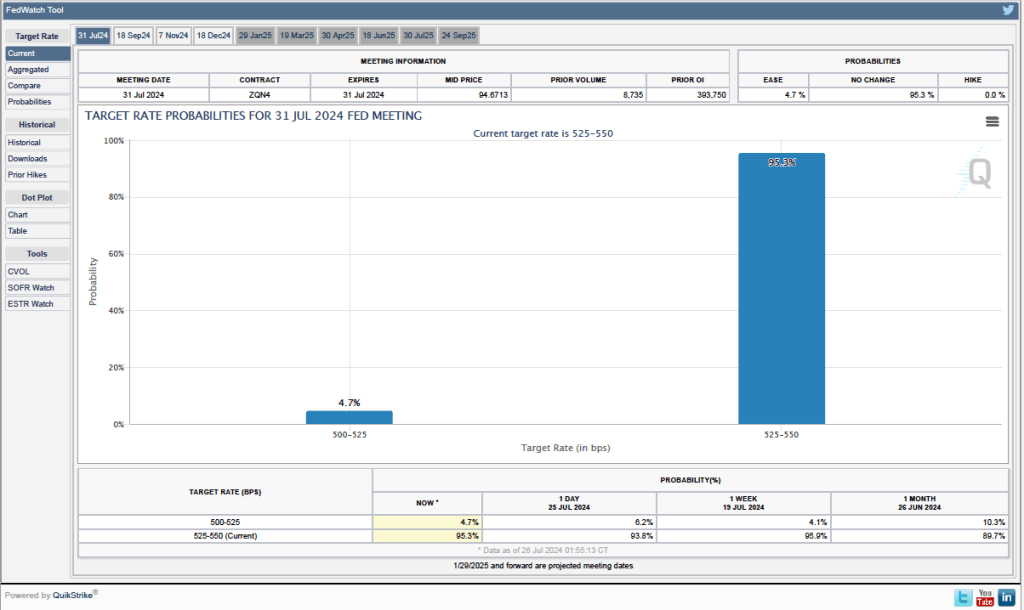

Futures markets allow investors to buy and sell futures contracts on commodities–such as wheat and oil–and on financial assets. Investors can use futures contracts both to hedge against risk—such as a sudden increase in oil prices or in interest rates—and to speculate by, in effect, betting on whether the price of a commodity or financial asset is likely to rise or fall. (We discuss the mechanics of futures markets in Chapter 7, Section 7.3 of Money, Banking, and the Financial System.) The CME Group was formed from several futures markets, including the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and allows investors to trade federal funds futures contracts. The data that result from trading on the CME indicate what investors in financial markets expect future values of the federal funds rate to be. The following chart from the CME’s FedWatch Tool shows the current values from trading of federal funds futures.

The probabilities in the chart reflect investors’ predictions of what the FOMC’s target for the federal funds rate will be after the committee’s July meeting. The chart indicates that investors assign a probability of only 4.7 percent to the FOMC cutting its federal funds rate target by 0.25 percentage point at its July 30-31 meeting and an 95.3 percent probability of the commitee leaving the target unchanged.

In contrast, the following figure shows that investors expect that the FOMC will cut its federal funds rate at the meeting scheduled for September 17-18. Investors assign an 87.7 percent probability of a 0.25 percentage point cut and a 11.9 percent probability of a 0.50 percentage point cut. The committee deciding to leave the target unchanged at 5.25 percent to 5.50 percent is effectively assigned a zero probability. In other words, investors believe with near certainty that the FOMC will reduce its target for the federal funds rate for the first time since the current round of rate increases ended in July 2023.