Image generated by ChatGTP 4o.

Recent macroeconomic data have been sending mixed signals about the state of the U.S. economy. The growth in real GDP, industrial production, retail sales, and real consumption spending has been slowing. Growth in employment has been a bright spot—showing steady net increases in job growth above the level necessary to keep up with population growth. Even here, though, as we discuss in a recent blog post, the data may be overstating the actual strength of the labor market.

This morning (July 5), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its “Employment Situation” report (often referred to as the “jobs report”) for June, which, while seemingly indicating continued strong job growth, also provides some indications that the labor market may be weakening. The jobs report has two estimates of the change in employment during the month: one estimate from the establishment survey, often referred to as the payroll survey, and one from the household survey. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 9.1 (Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.1), many economists and policymakers at the Federal Reserve believe that employment data from the establishment survey provides a more accurate indicator of the state of the labor market than do either the employment data or the unemployment data from the household survey. (The groups included in the employment estimates from the two surveys are somewhat different, as we discuss in this post.)

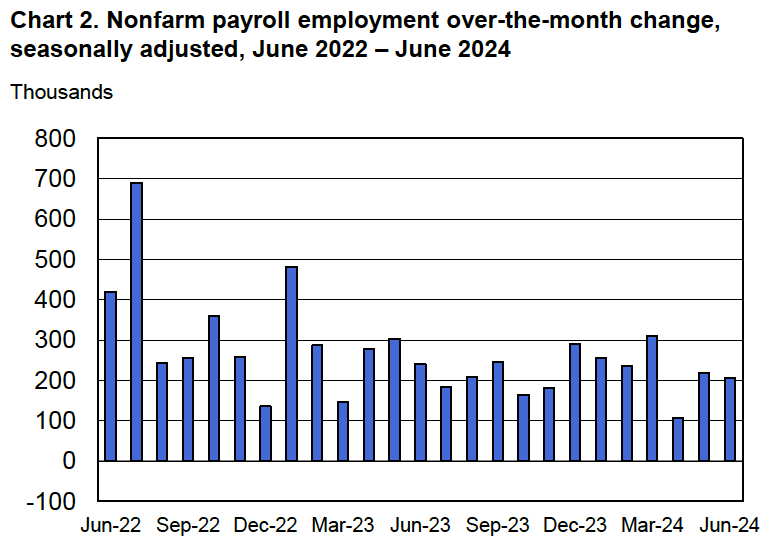

According to the establishment survey, there was a net increase of 206,000 jobs during April. This increase was a little above the increase of 1900,000 to 200,000 that economists had forecast in surveys by the Wall Street Journal and bloomberg.com. The following figure, taken from the BLS report, shows the monthly net changes in employment for each month during the past to years.

It’s notable that the previously reported increases in employment for April and May were revised downward by 110,000 jobs, or by about 25 percent. (The BLS notes that: “Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.”) As we’ve discussed in previous posts (most recently here), revisions to the payroll employment estimates can be particularly large at the beginning of a recession.

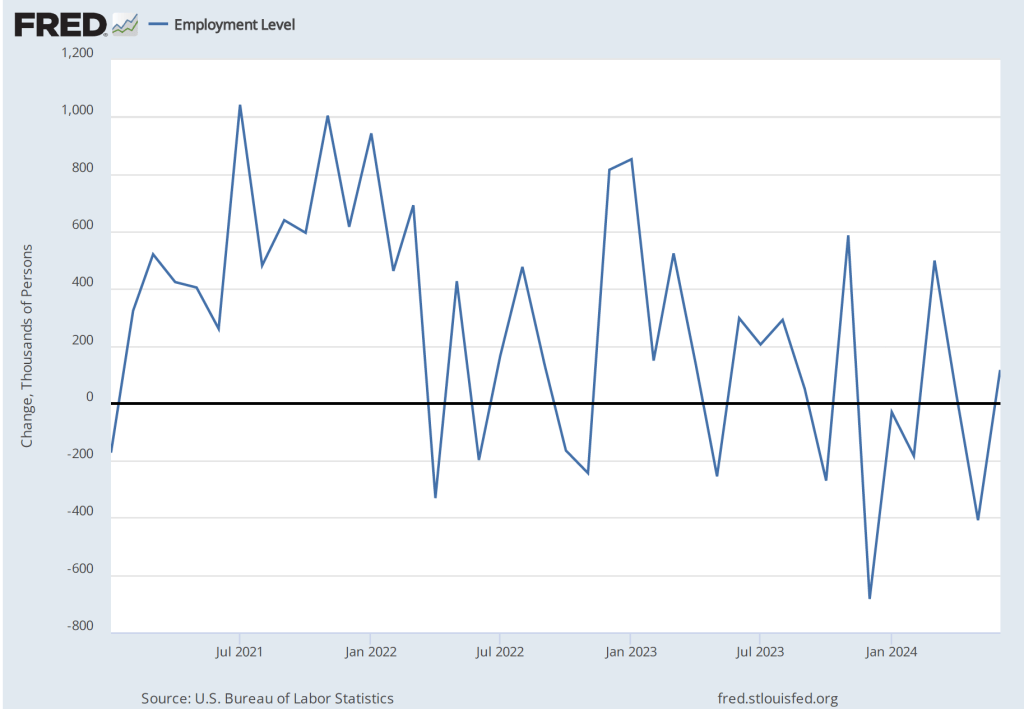

As the following figure shows, the net change in jobs from the household survey moves much more erratically than does the net change in jobs in the establishment survey. The net increase in jobs as measured by the household survey increased from –408,000 in May (that is, employment by this measure fell during May) to 116,000 in June.

Note that the BLS also reports a survey for household employment adjusted to conform to the concepts and definitions used to construct the payroll employment series. After this adjustment, over the past 12 months household employment has increased by 32.5 million less than has payroll employment. Clearly, this is a very large discrepancy and may be indicating that the payroll survey is substantially overstating growth in employment.

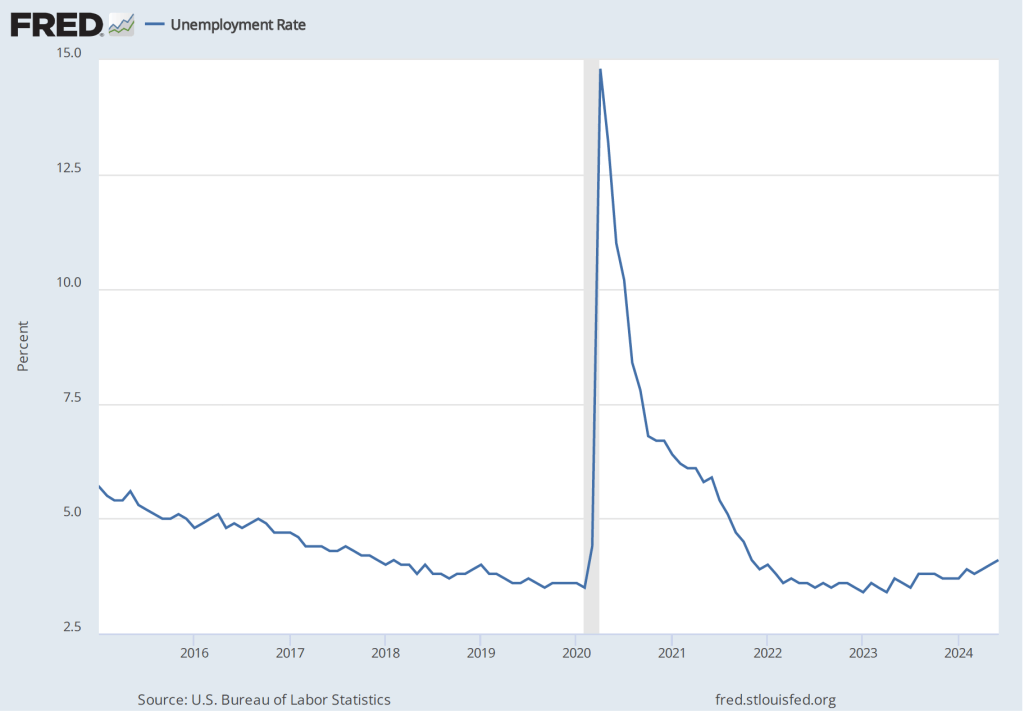

The unemployment rate, which is also reported in the household survey, ticked up slightly from 4.0 percent to 4.1 percent. Although still low by historical standards, June was the fourth consecutive month in which the unemployment rate increased.

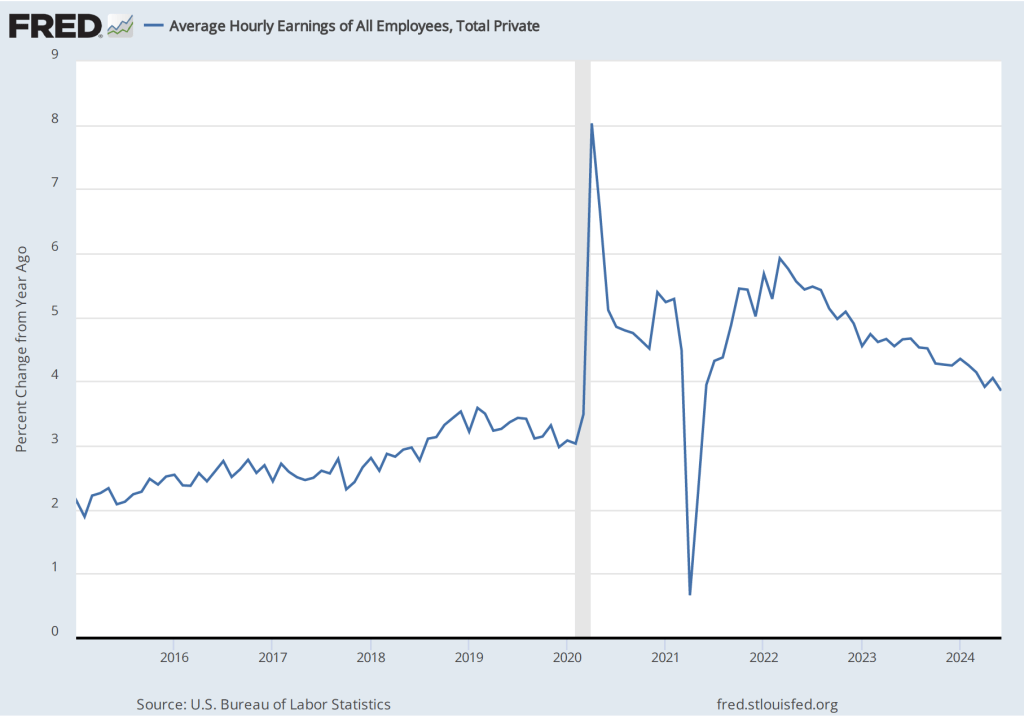

The establishment survey also includes data on average hourly earnings (AHE). As we note in this post, many economists and policymakers believe the employment cost index (ECI) is a better measure of wage pressures in the economy than is the AHE. The AHE does have the important advantage that it is available monthly, whereas the ECI is only available quarterly. The following figure show the percentage change in the AHE from the same month in the previous year. The 3.9 percent increase for June continues a downward trend that began in January and is the smallest increase since June 2021.

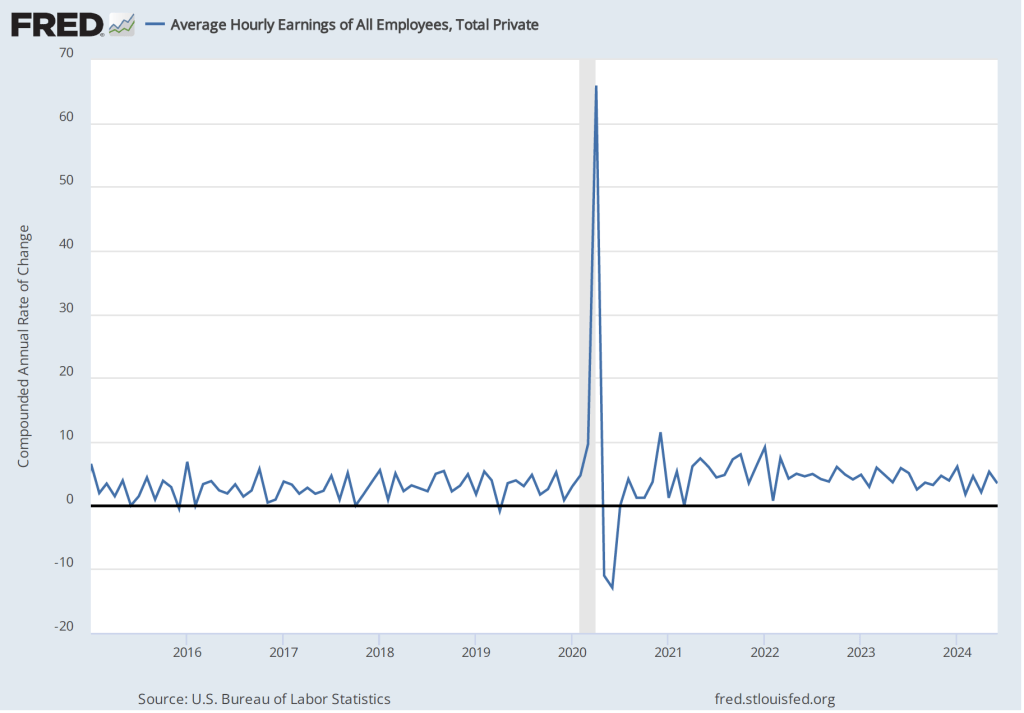

The following figure shows wage inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month wage inflation, whereas this figure shows 1-month wage inflation.) One-month wage inflation is much more volatile than 12-month inflation—note the very large swings in 1-month wage inflation in April and May 2020 during the business closures caused by the Covid pandemic.

The 1-month rate of wage inflation of 3.5 percent in June is a significant decrease from the 5.3 percent rate in May, although it’s unclear whether the decline was an additional sign that the labor market is weakening or reflected the greater volatility in wage inflation when calculated this way.

What effect is today’s job reports likely to have on the Fed’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee as it considers changes in its target for the federal funds rate? As always, it’s a good idea not to rely too heavily on a single data point—particularly because, as we noted earlier, the establishment survey employment data is subject to substantial revisions. But the Wall Street Journal’s headline that the “Case for September Rate Cut Builds After Slower Jobs Data,” seems likely to be accurate.