Photo of Caitlin Clark when she played for the University of Iowa from Reuters via the Wall Street Journal.

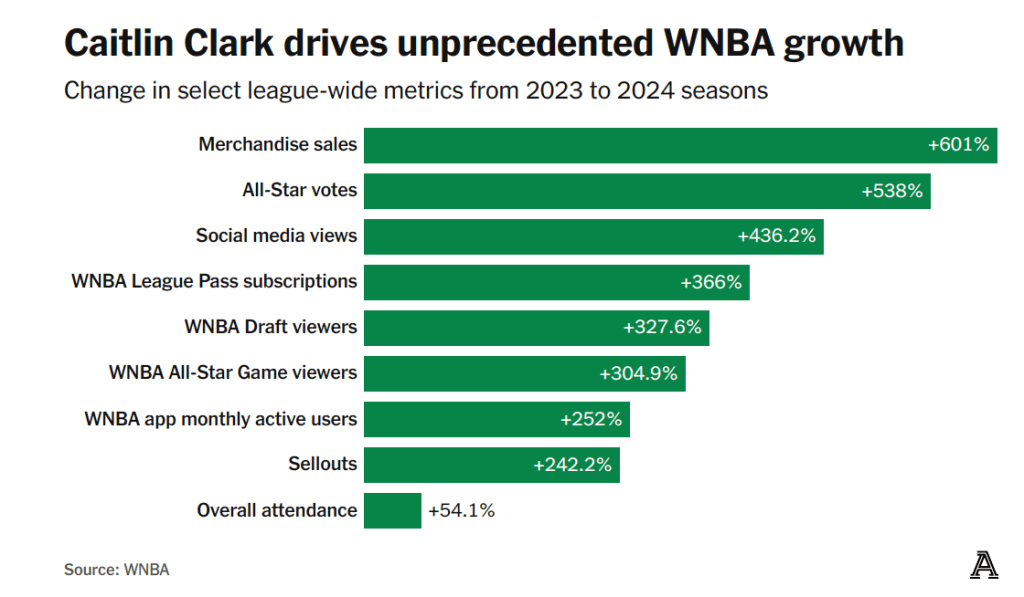

Caitlin Clark’s ability to hit three-point shots made her a star at the University of Iowa. Since she joined the Indiana Fever of the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) in 2024, she’s been, arguably, the league’s biggest star. An article on theathletic.com discussing Clark’s effect on the league includes the following chart:

Clark’s popularity has resulted in substantially increased revenue for her team and for the WNBA. Should that fact affect the salary she receives from the Indiana Fever? The article states that: “Clark will almost assuredly never receive in salary what she is worth to the WNBA. In that regard, she’s a lot like [former men’s basketball star Michael] Jordan, and other all-time greats across sports.” Why won’t Clark be paid a salary equal to her worth to the WNBA?

In Microeconomics, Chapter 16, we show that in a competitive labor market, workers receive the value of their maginal products. The value of a basketball player’s marginal product is the additional revenue the player’s team earns from employing the player. We note that the marginal product of an athlete is the additional number of games the athlete’s team wins by employing the player. The value of a player’s marginal product is the additional revenue the team earns from those additional wins. Teams that win more games attract more fans to watch the teams play—both in person and on television or online. Teams earn revenue from selling tickets, as well as concessions and souvenirs sold in the area. Teams are paid for the rights to broadcast or stream their games. And, as the chart above shows, a player as popular as Clark will increase the game jerseys and other merchandise a team can sell.

We note in Chapter 16 that, once their inital contracts with their teams expire, the best professional athletes tend to sign contracts with teams in larger cities. Although an athlete’s marginal product may be no larger in a big city than in a smaller city, the revenue a team earns from the additional games the team wins from employing a star athlete depends in part on the population of the city the team plays in. Clark’s 2025 salary is only $78,066, far below the value of her marginal product, which is likely at least several million dollars. Her current contract with the Fever lasts through the 2027 season. But even after the contract expires, by league rules, she can’t be paid more than $294,244 by whichever team signs her. (It’s possible that amount may have increased by the time her current contract expires.)

The ceiling on WBNA salaries is far below the average salary in most U.S. men’s professional leagues. For instance, the average salary in the men’s National Basketball Association (NBA) during the 2024–2025 year was nearly $12 million. A low salary cap is common in leagues that are relatively new or that aren’t popular enough to receive large payments for the rights to broadcast or stream their games. For example, men’s Major League Soccer (MLS) has a salary limit of about $6 million per team. The WNBA was founded in 1996 (the NBA was founded in 1946) and, although the broadcast and online viewership for its games has increased, its viewership remains well below the NBA’s viewership.

Clark has been earning millions of dollars from endorisng Nike, Gatoade, and other products. But unless the factors just discussed change, it seems unlikely that she will receive a salary equal to the value of her marginal product to the Fever or any WNBA team she might play for in the future. The excerpt from theathletic.com article that we quoted above, though, compares her salary not to the value of her marginal product to the Fever but to the WNBA as a whole. Are there any circumstances under which we might expect a major sports star to be paid a salary equal to the additional revenue he or she is generating for a league as a whole?

The quotation from the article notes that no “all-time great” players, inclduing Michael Jordan of the NBA, have received salaries equal to the value of their marginal product to the leagues they played in. This outcome shouldn’t be surprising. Returns that entrepreneurs or workers earn in a market system are typically well below the total value they provide to society. For example, in a classic academic paper Nobel laureate William Nordhaus of Yale University estimated that entrepreneurs keep just 2.2 percent of the economic surplus they create by founding new firms. (We discuss the concept of economic surplus in Microeconomics, Chapter 4.) Leaving aside the monetary value of Clark to her team and her league, she has provided substantial consumer surplus to viewers of her games that is not captured by arena ticket prices or cable or streaming subscriptions. As we discuss in Chapter 4, the same is true of most goods and services in competitive markets.

Caitlin Clark, like Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, has only received a small fraction of the economic surplus she has created. (Photo from the Wall Street Journal)

So, although Caitlin Clark is a millionaire as a result of the money she has been paid to endorse products, the actual additional value she has created for her team, her league, and the economy is far greater than the income she earns.

“Clark will almost assuredly never receive in salary what she is worth to the WNBA. In that regard, she’s a lot like [Michael] Jordan, and other all-time greats across sports.”