Image generated by GTP-4o of “an apartment building in Amersterdam.”

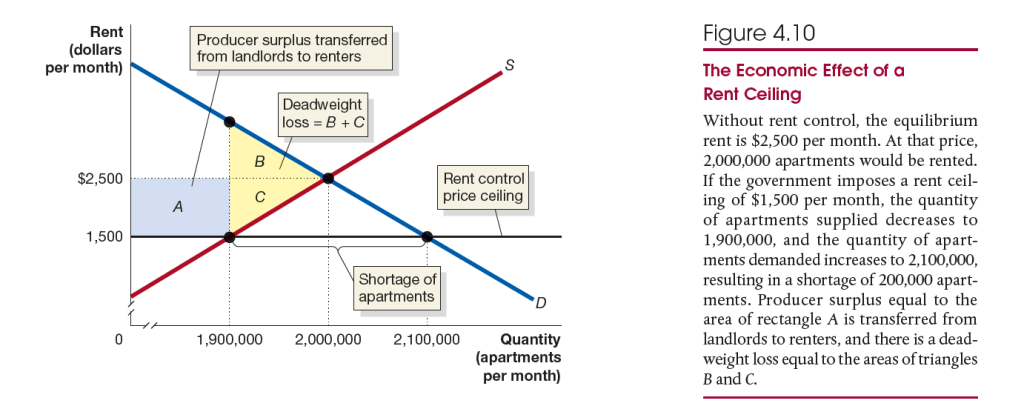

Recent articles in the media discussed the effects of rent control on the market for apartments in the Netherlands and in Stockholm, the capital of Sweden. The articles describe a situation that is consistent with the analysis in Chapter 4, Section 4.3. Figure 4.10 shows the expected results from the imposition of a rent control law. Some renters gain by living in apartments at below the equilibirum market rent, but the shortage of apartments resulting from the price ceiling means that some renters are unable to find apartments. As with other price controls, rent ceilings impose a deadweight loss on the economy, shown in the figure as the areas B + C.

An article on bloomberg.com discusses the effect on the market for apartments in the Netherlands of the passage in June of the Affordable Rent Act. The act raised the fraction of apartments covered by rent control from about 80 percent to 96 percent. The expansion of rent control appears to have led to an increased shortage of apartments. The article quotes one teacher who has been unable to find an apartment for her family as saying: “The cost isn’t the problem, but a real shortage of housing is.”

The article indicates that some landlords who doubt they can earn a profit under the new law are selling their buildings. If the buildings are converted to other uses, the shortage of apartments will be increased. The article mentions another unintended change to the apartment market from the provision of the new law that requires leases to be open-ended. Some landlords fear that as a result they may find themselves unable to evict tenants, however troublesome the tenants may be. In response, these landlords are giving priority to foreigners, who they believe are likely to move more often.

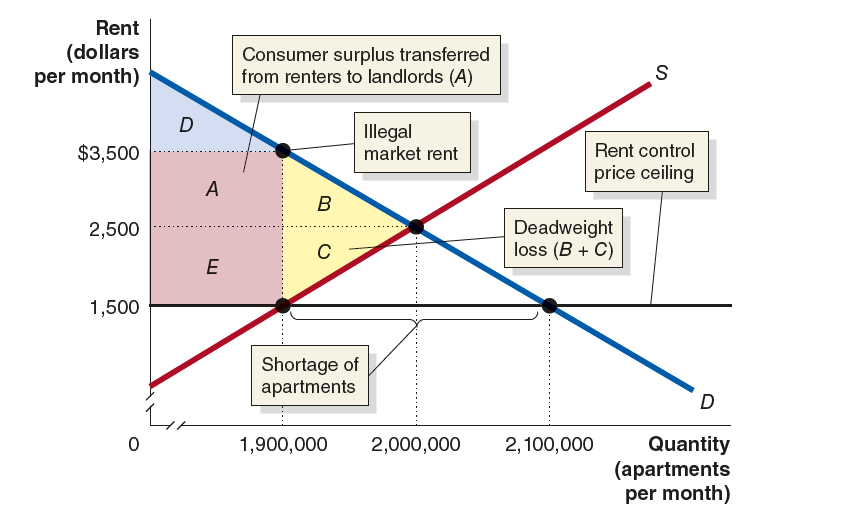

An article in the Economist looks at another aspect of rent control. The following figure is reproduced from Solved Problem 4.3. It shows that because rent control leads to a shortage of apartments it creates an incentive for tenants and landlords to agree to a rent that is higher than the legal rent ceiling. In this example, renters who are unable to find an apartment at the rent control ceiling of $1,500 may bid up the rent to $3,500—which in this example is $1,000 higher than the market equilibrium rent in the absence of rent control—rather than not be able to rent an apartment. Clearly, renters paying this illegal rent are worse off than they would be if there were no rent control law.

According to the article in the Economist, the average time on a waiting list for a rent controlled apartment is 20 years. Not surprisingly, “Young Swedes often have to put up with expensive sublets agreed to under the table,” for which they typically pay rents above both the rent control ceiling and the market equilibrium rent. Most economists agree that expanding the quantity of available housing by making it easier to build homes and apartments is a better way of reducing housing costs than is imposing rent controls.