Cracker Barrel’s original logo on the left and the logo it temporarily adopted in 2025 on the right. (Logos from nrn.com)

Dan Evins opened the first Cracker Barrel Old Country Store on Highway 109 in Lebanon, Tennessee in 1969 to attract more customers to his Shell service station. The restaurant offered traditional Southern-style food such as buttermilk biscuits, country-fried steak, and chicken and dumplings. Cracker Barrel was an immediate success and by 1977 had expanded to 13 locations in Tennessee and Georgia, with each location including a restaurant and an attached store designed to resemble the traditional general stores that were once common in rural areas. In 2026, Cracker Barrel had 657 locations in 44 states.

In Chapter 13, we study monopolistically competitive markets. One key feature of these markets is low barriers to entry. So we would expect that in a monopolistically competitive market such as restaurants, if an entrepreneur uses a new strategy that earns an economic profit, that strategy is likely to be copies by other firms. A number of other restaurant chains compete with Cracker Barrel offering similar menus and approaches that are intended to appeal to consumers who are older, likely to live in rural or suburban areas—particularly in the South and Midwest—and prefer traditional country-style cooking. These competitors include Golden Corral, Bob Evans, Black Bear Diner, Denny’s, and Waffle House. The entry into the market and expansion of these chains resulted in declining profits for Cracker Barrel. The chain also lost breakfast customers to IHOP, McDonald’s, and Eggs Up Grill.

In 2020, Cracker Barrel was severely affected by the Covid pandemic because many of its older customers were reluctant to eat in restaurants. Even after the effects of the pandemic had passed, Cracker Barrel’s profit continued to decline, falling from $255 million in 2021 to $40 million in 2024. In response to this falling profit, in 2024 the firm’s board of directors hired Julie Felss Masino as CEO to lead a “strategic transformation.” On being hired, Masino stated that: “We know from our research that despite high levels of consumer affinity, we’re just not as relevant as we once were. We need to address these dynamics by refreshing and refining the brand ….”

Masino oversaw a $700 million plan to transform the chain by renovating the restaurants including removing many of the vintage signs, knickknacks, tools, and photos that had decorated walls, changing the marketing approach, and updating the menu by dropping some items and adding 20 new items such as New York strip steaks, chicken sandwiches, Mimosas, and Strawberry Peach Lemonade. The aim was to attract younger and more urban customers.

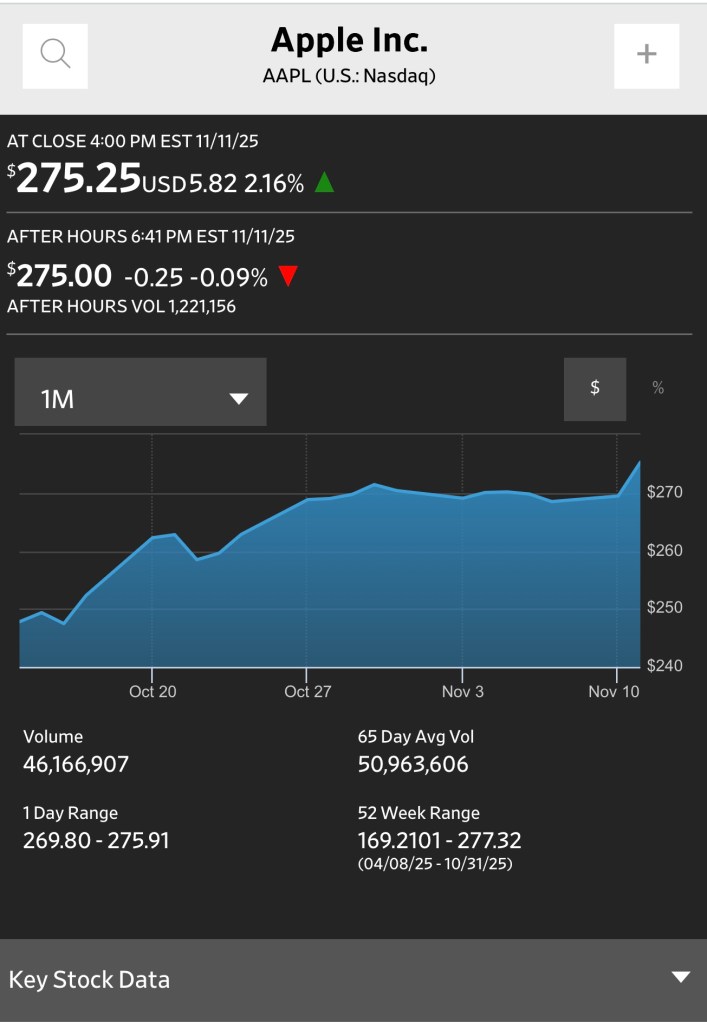

Many long-time customers were opposed to changes but, overall, initially revenue and profit increased. Then in August 2025, Cracker Barrel introduced a new more streamlined and modern logo that, importantly, eliminated from the logo the drawing of an older man—often referred to as “Old Timer”—sitting on a chair with his arm on a barrel. The change led to an immediate negative response on social media from Cracker Barrel customers. The controversy was soon widely covered in the business media and elsewhere. The number of customers in Cracker Barrel’s restaurants declined by 8 percent and its stock price dropped by 40 percent as investors concluded that the firm’s rebranding was a major error that it might have difficulty coming back from.

After only a week, Masino and other company executives reversed course and reverted to using the older logo. The company also suspended the plan to remodel its restaurants and restored to its menu some items that it had dropped. Masino was quoted as stating that: “We are doubling down on delicious, scratch-made food the way our guests expect it and that great country hospitality that we’re known for.”

Will Cracker Barrel be able to bounce back from reversing its strategy of modernizing its restaurants, its menu, and its marketing to appeal to younger urban customers? It has a difficult task. The chain was originally intended to appeal to particular market niche. As competition for consumers in that niche increased and as the number of those consumers declined, the chain was faced with a difficult choice: Either reduce costs sufficiently to remain profitable with fewer customers or change its strategy in an attempt to appeal to new customers. They chose to do some of both, making the changes discussed earlier and also cutting costs in food preparation. The cost cutting was also criticized as customers objected to such changes as making its signature biscuits in large batches rather than making them as needed and reheating green beans rather than cooking them on demand. In early 2026, the outlook for the chain didn’t appear promising.

Sources: Heather Haddon, “Now Cracker Barrel Diehards Think the Food Isn’t Up to Scratch, Either,” Wall Street Journal, December 9, 2025; Nathaniel Meyerson, “Cracker Barrel Isn’t Doomed Just Yet,” edition.cnn.com, September 13, 2025; Dee-Ann Durbin, “Cracker Barrel Is Keeping Its Old-Time Logo after New Design Elicited an Uproar,” apnews.com, August 27, 2025; Dee-Ann Durbin, “Breakfast Is Booming at US Restaurants. Is It Also Contributing to High Egg Prices?” apnews.com, February 13, 2025; Heather Haddon, “After a Bruising Year, Casual-Dining Chains Try to Stage a Comeback,” Wall Street Journal, June 20, 2025; Cracker Barrel Old Coun-try Store, “Cracker Barrel Launches Flavor Packed Summer Menu Featuring Exclusive New Beed Sting Fried Chicken, Plus More,” prnewswire.com, May 8, 2024; Joanna Fantozzi, “Cracker Bar-rel Unveils ‘Strategic Transformation’ Amid Financial Struggles,” nrn.com, May 18, 2024; Lynn and Cele Seldon, “Cracker Barrel Anniversary,” trailblazer.thousandtrails.com, September 12, 2019; “About Cracker Barrel,” crackerbarrel.com; and Cracker Barrel Old Country Store, Annual Report, various years.