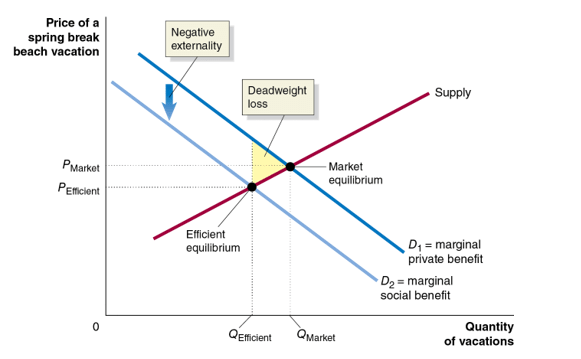

Supports: Microeconomics and Economics, Chapter 6, and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 7, Section 7.5-7.7

ChatGTP-4o image of cars in the Lincoln Tunnel, which connects New Jersey with midtown Manhattan.

In January 2025, New York City began enforcing congestion pricing in the borough of Manhattan south of 60th Street—the congestion relief zone. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) in New York collects a toll from a vehicle entering that zone either automatically using the vehicle’s E-ZPass transponder or by reading the vehicle’s license plate and mailing a bill to the vehicle’s owner. Nobel Laureate William Vickrey of Columbia University first proposed congestion pricing in the 1950s as a way to deal with the negative externalities from traffic congestion. Congestion pricing acts as a Pigovian tax that internalizes the external costs drivers generate by using streets in congested areas. (We discuss Pigovian taxes in Microeconomics and Economics, Chapter 5, Section 5.3, and in Essentials of Economics, Chapter 4, Section 4.3.)

The New York City congestion toll is somewhat complex, varying according to the type of vehicle and how the vehicle enters the area in which the toll applies. The congestion toll fora car entering Manhattan through the Lincoln Tunnel on a weekday between 5 am and 9 pm is $6.00 on top of the existing toll of $16.06. In January 2025, the volume of cars driving through the Lincoln Tunnel declined by 8 percent during the weekday hours of 5 am to 9 pm. According to an article in Crain’s New York Business, the number of vehicles entering the congestion relief zone compared with the same month in the previous year declined by 8 percent in January, 12 percent in February, and 13 percent in March.

- From the information given, can we determine the price elasticity of demand for entering Manhattan by driving though the Lincoln Tunnel during weekdays from 5am to 9am? Briefly explain.

- Suppose someone makes the following claim: “Because the quantity of cars using the Lincoln Tunnel has declined by 8 percent, we know that the MTA must have collected less revenue from cars using the tunnel than before the congestion toll was imposed.” Briefly explain whether you agree.

- Is the pattern of increasing percentage declines in vehicle traffic in the congestion relief zone each month from January to March what we would expect? Be sure your answer refers to concepts related to the price elasticity of demand.

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about the price elasticity of demand, so you may want to review Chapter 6, Sections 6.1-6.4.

Step 2: Answer part (a) by explaining whether from the information given we can determine the price elasticity of demand for entering Manhattan by driving through the Lincoln Tunnel. We do have sufficient information to determine the price elasticity, provided that nothing else that would affect the demand for driving through the Lincoln Tunnel changed during January. We’re told the percentage change in the quantity demand, so we need only to calculate the percentage change in the price to determine the price elasticity. The change in the price is the $6 congestion toll. The average of the price before and the price after the toll is imposed is ($16.06 + $22.06) = $19.06. Therefore, the percentage change in the price is ($6/$19.06) × 100 = 31.5 percent. The price elasticity of demand is equal to the percentage change in quantity dmanded divided by the percentage change in price: –6%/31.5% = –0.3. Because this value is less than 1 in absolute value, we can conclude that the demand for driving through the Lincoln Tunnel is price inelastic.

Step 3: Answer part (b) by explaining whether because the quantity of cars driving through the Lincoln Tunnel has declined the MTA must have collected less revenue from cars using the tunnel. As shown in Section 6.3 of the textbook, total revenue received will fall after a price increase only if demand is price elastic. In this case, demand is price inelastic, so the total revenue the MTA collects from cars using the Lincoln Tunnel will rise, not fall.

Step 3: Answer part (c) by explaining whether the pattern of increasing percentage declines in vehicle traffic in the congestion relief zone is one we would expect. In Section 6.2, we see that the passage of time is one of the determinants of the price elasticity of demand. The more time that passes, the more price elastic the demand for a product becomes. In other words, the longer the time that people have to adjust to the congestion toll—by, for instance, taking a bus rather than driving through the Lincoln Tunnel in a car—the more likely it is that people will decide not to drive into the congestion relief zone. So, it is not surprising that the number of vehicles entering the congestion relief zone declined by a greater percentage each month from January to March.