Image generated by GTP-4o to illustrate GDP.

About one month after a calendar quarter ends, the Bureau of Economic Analyis (BEA) releases its advanced estimate of real GDP. In July 2022, the BEA’s advance estimates indicated that real GDP had declined in both the first and second quarters. A common definition of a recession is two consecutive quarters of declining real GDP. Accordingly, in mid-2022 there were a number of articles in the media suggesting that the U.S. economy was in a recession.

But, as we discussed at the time in this blog post, most economists don’t follow the popular definition of a recession as being two consecutive quarters of declining real GDP. Instead, as we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 10, Section 10.3 (Economics, Chapter 20, Section 20.3), economists typically follow the definition of a recession used by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER): “A recession is a significant decline in activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, visible in industrial production, employment, real income, and wholesale-retail trade.”

During the first half of 2022, the other data that the NBER tracks were all expanding rather than contracting. So, it seemed safe to conclude that despite the declines in real GDP in those quarters, the U.S. economy was not, in fact, in a recession.

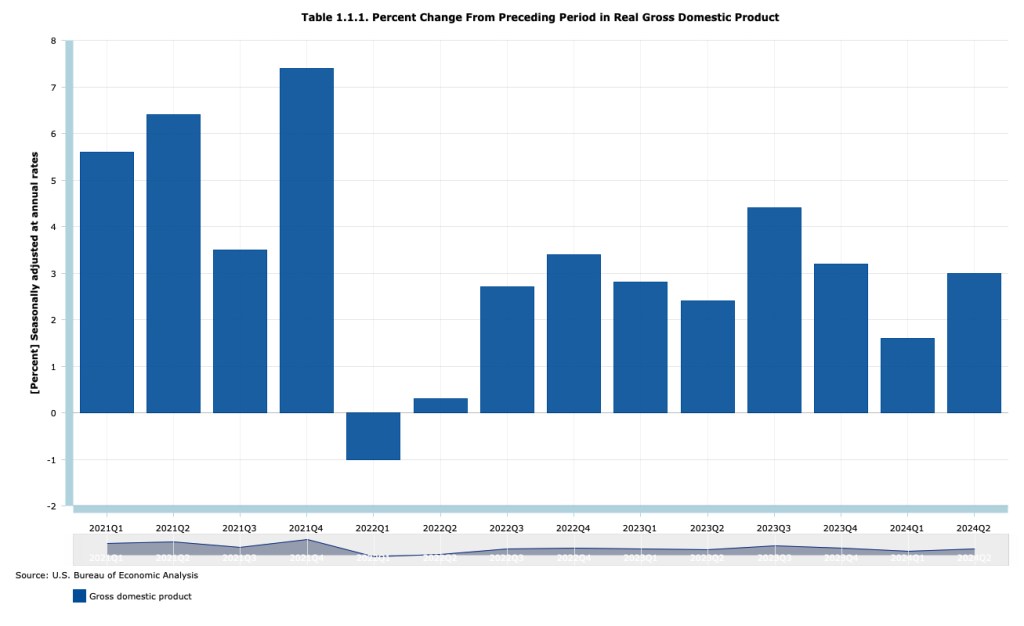

That conclusion was confirmed by the BEA in September 2024 when it released its most recent revisions of real GDP . As the following table shows, although the BEA still estimates that real GDP fell during the first quarter of 2022, it now estimates that it increased during the second quarter.

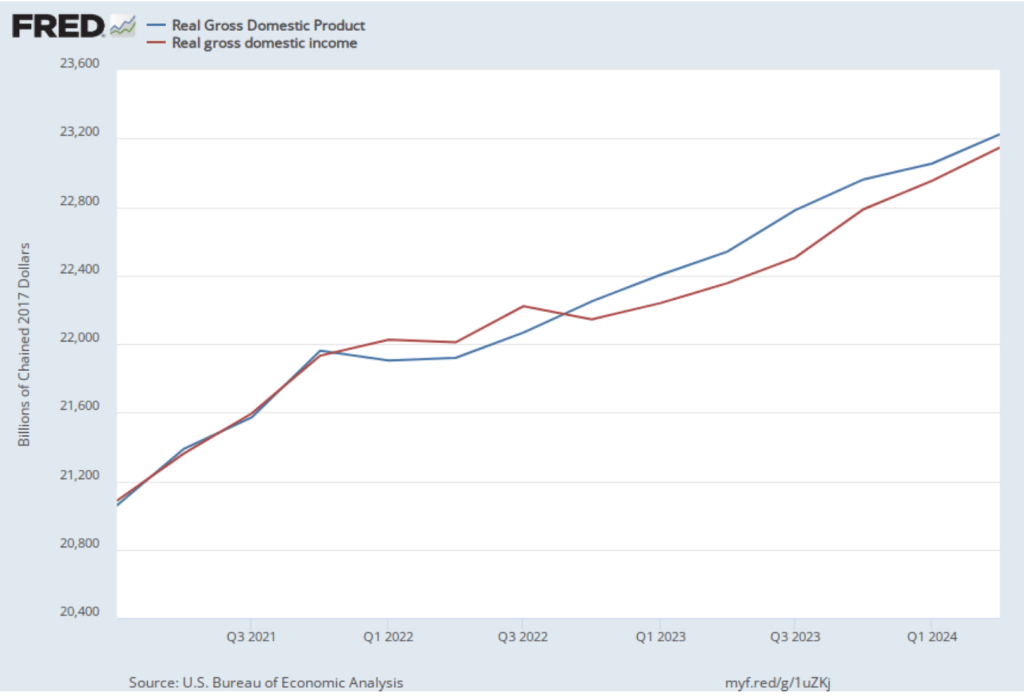

In the earlier post from 2022, we also noted that the BEA publishes data on gross domestic income (GDI), as well as on GDP. As we discuss in Chapter 8, Section 8.1, when considering the circular-flow diagram, the value of every final good and service produced in the economy (GDP) should equal the value of all the income in the economy resulting from that production (GDI). The BEA has designed the two measures to be identical by including in GDI some non-income items, such as sales taxes and depreciation. But as we discuss in the Apply the Concept, “Should We Pay More Attention to Gross Domestic Income?” GDP and GDI are compiled by the BEA from different data sources and can sometimes significantly diverge.

We noted that although, according to the BEA’s advance estimates, real GDP declined during the first two quarters of 2022, real GDI increased. The following figure shows movements in real GDP and real GDI using the current estimates from the BEA. The revised estimates now show real GDP falling the first quarter of 2021 and increasing in the second quarter while real GDI is still estimated as rising in both quarters. The revisions closed some of the gap between real GDP and real GDI during this period by increasing the estimate for real GDP, which indicates that the advance estimate of real GDI was giving a more accurate measure of what was happening in the U.S. economy.

The figure shows that the revised estimates indicate that real GDP and real GDI moved closely together during 2021, differed somewhat during 2022—with real GDI being greater than real GDP—and differed more substantially during 2023 and 2024—with real GDP now being greater than real GDI. Because the two measures should be the same, we can expect that further revisions by the BEA will bring the two measures closer together.

It’s even possible, but unlikely, that further revisions of the data for 2022 could again present us with the paradox of real GDP declining for two quarters despite other measures of economic activity expanding.