This pair of ruby slippers worn by Judy Garland playing the role of Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz sold at auction last December for $32.5 million.

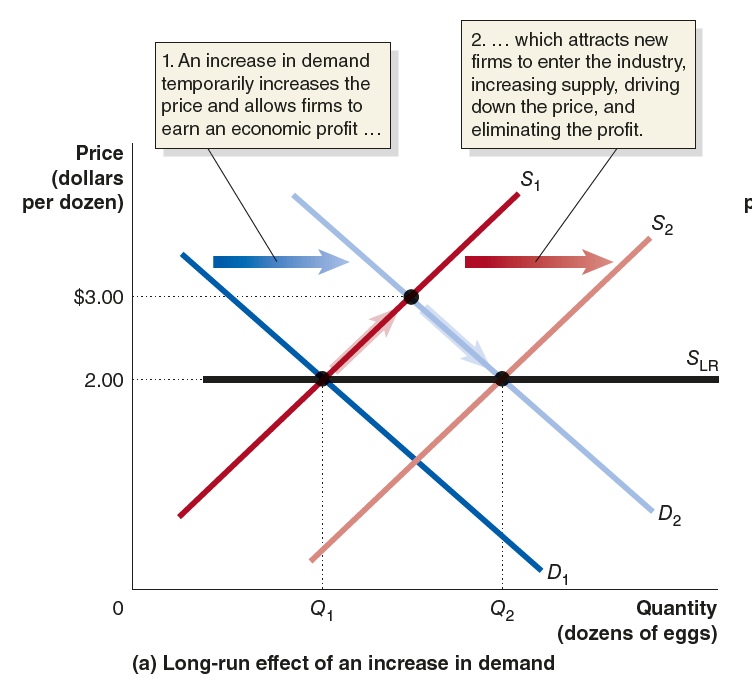

One of the most important ideas in economics is that an increase in the price of a good attracts new entrants into that market. In the short run, before there is time for new firms to enter an industry, an increase in price leads to a movement up the supply curve for the good (an increase in the quantity supplied). In the long run, a higher price leads to the entry of new firms (an increase in supply), which forces the price of the good back down to the level at which firms in the industry just break even. The following figure from Microeconomics, Chapter 12 illustrates the effects of entry in the case of the market for cage-free eggs. An increase in demand occurs when the price is $2.00 per dozen. The increased demand forces a price increase to $3.00, but, over time, entry of new firms forces the price back down to $2.00.

But what if the supply of a good is fixed, as in the case of collectibles such as the props used in a movie? In that situation, we would expect that entry is impossible. Demand for props used in movies—particularly classic movies—has soared in recent years leading to sharply increased prices. A pair of ruby slippers (as they are usually called even though they are actually shoes rather than slippers) used in the filming of The Wizard of Oz sold at auction in December for $32.5 million. Shown below is the “Rosebud” sled used in the filming of Citizen Kane—thought by some critics to be the greatest film ever made. It sold for $14.75 million in June of this year.

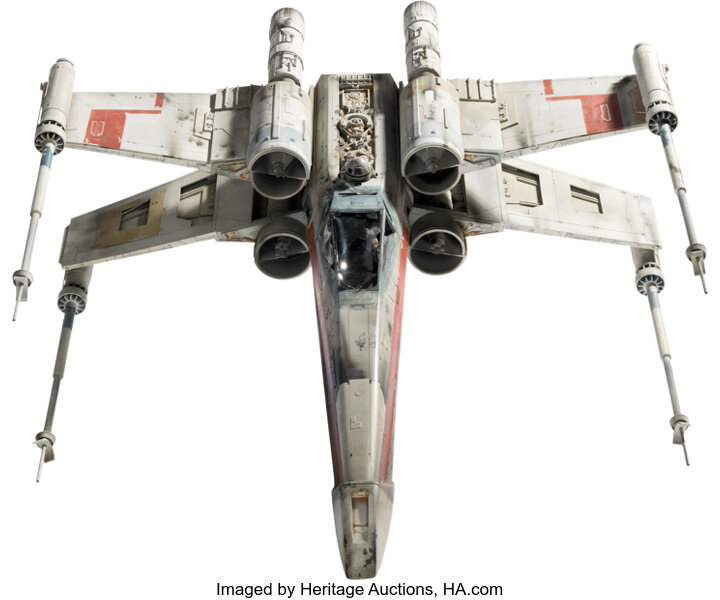

The model of an X-Wing Starfighter shown below was used in filiming the first Star Wars film and sold at auction for $3.135 million.

Unlike with cage-free eggs, these high prices won’t attract new entry because the value of these goods comes from their having been used in the making of classic films. (Of course, the high prices may lead some people who own similar props from these movies to offer them for sale—a movement up the supply curve, rather than a shift in the curve.)

According to a recent article in the Los Angeles Times (a subscription may be required), some unscrupulous people have attempted to enter the market for collectible movie props by creating counterfeits. According to the article, 3D printers have made it easier for scammers to create duplicates of movie props. For instance, according to the article, earlier this year an auction house advertised that it would be offering for sale the only surviving Han Solo DL-44 blaster used in the filming of the first Star Wars movie. (Shown in the image below, which was generated by ChatGPT.) The auction house estimated that the blaster could sell for more than $3 million.

Collectors carefully analyzed the photos shown on the auction site and discovered several discrepancies between the prop being offered for sale and the actual prop used in the film. The auction house concluded that the prop was a counterfeit and withdrew it from sale.

The article quoted Jason Henry, who is a television producer and who makes online videos on movie collectibles, as saying:

“As the prices go up, the supply is going up as well, which doesn’t seem like that’s how it should be. And it’s not because there’s actually more of the original pieces, there’s actually just more fakes or questionable pieces as we like to call it, that are flying into the market.”

It’s unfortunate, but unsurprising to an economist, that in this case the very strong incentive to enter a profitable industry has led some people to break the law by creating counterfeit movie props.