A fundamental point in macroeconomics is that the value of income and the value of output or production are the same. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) measures the value of the U.S. economy’s production with gross domestic product (GDP) and the value of total income with gross domestic income (GDI). The two numbers are designed to be equal but because they are compiled from different data, the numbers can diverge. (We discuss GDP and GDI in the Apply the Connection “Was There a Recession during 2022? Gross Domestic Product versus Gross Domestic Income” in Macroeconomics, Chapter 8, Section 8.4 (Economics Chapter 18, Section 18.4).)

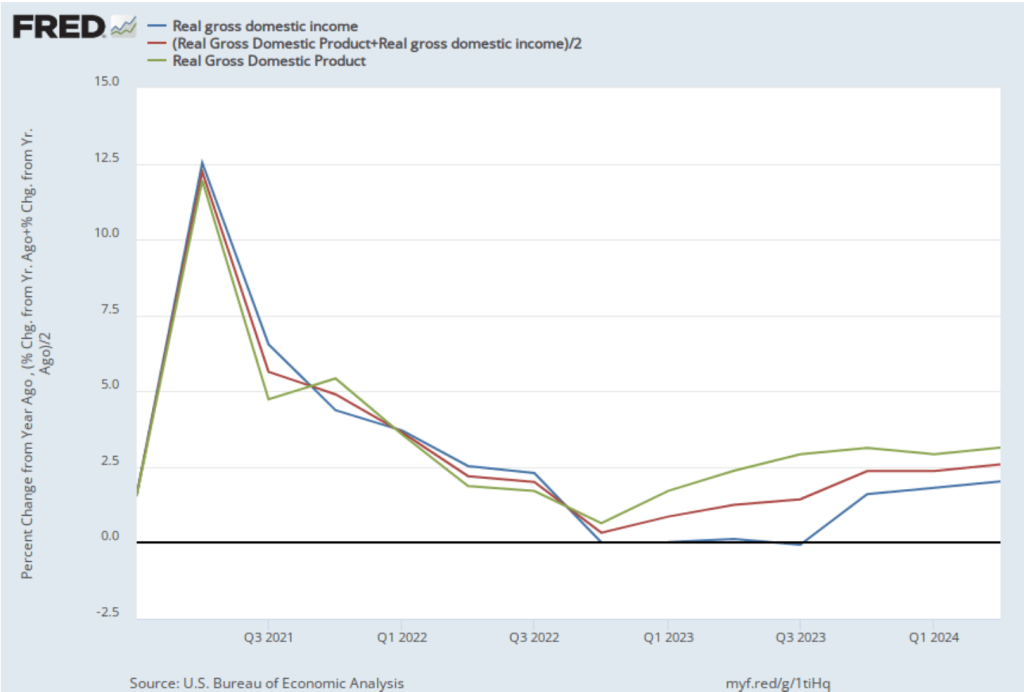

The figure above shows that in the past two years the growth rate of real GDP (the green line in the figure) has been significantly different—significantly higher—than the growth rate of GDI (the blue line). Both growth rates are measured as the percentage change from the same quarter in the previous year. Until the fourth quarter of 2022, the two growth rates were roughly similar over the period shown. But for the four quarters beginning in the fourth quarter of 2022, real GDI was flat with a growth rate of 0.0 percent, while real GDP grew at an average annual rate of 1.9 percent during that period. From the fourth quarter of 2023 through the second quarter of 2024, real GDI grew, but at an average annual rate of 1.8 percent, while real GDP was growing at a rate of 3.1 percent. (Some economists prefer to average the growth rates of GDP and GDI, which we show with the red line in the figure.)

In other words, judging by growth in real GDI, the U.S. economy was experiencing something between stagnation and moderate growth, while judging by growth in real GDP, the U.S. economy experiencing moderate to strong growth. There can be differences between GDP and GDI because (1) the BEA uses data on wages, profits, and other types of income to measure GDI, and (2) the errors in these data can differ from the errors in data on production and spending used to estimate GDP.

Jason Furman, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama, has suggested that a surge in immigration may explain why GDI growth has lagged GDP growth. As we discuss in this blog post, the Census Bureau may have been underestimating the number of immigrants who have entered the United States in recent years. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that there are actually 6 million more people living in the United States in 2024 than the Census Bureau estimates because the bureau has underestimated the number of immigrants.

Compared to the native-born population, immigrants are disproportionately in the prime working ages of 25 to 54 and are therefore more likely to be in the labor force. It seems plausible—although so far as we know, the point hasn’t been documented—that the value of production resulting from the work of uncounted (in the census estimates) immigrants is more likely to be included in GDP than the income they are paid is to be counted in GDI. The result could explain at least part of the discrepancy between GDP and GDI that we’ve seen in the past two years. But while this factor affects the levels of GDP and GDI, it’s not clear that it affects the growth rates of GDP and GDI. The number of uncounted immigrants would have to be increasing over time for the growth rate of GDI to be reduced relative to the growth rate of GDP.

This episode may demonstrate the need for Congress to provide the BEA staff with resources they would need to do the work required to reconcile GDP estimates with GDI estimates.